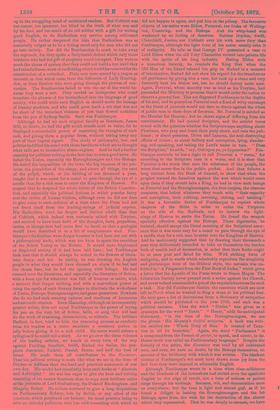

ALBANY FONBLANQUE.

-LIVEN among those who had read every page of "England -121 Under Seven Administrations," and who had often taken down the volumes from the book-shelves to get a deep draught of their delightful wit and pure English, there must have been many who were strangely surprised when they heard the other day that Albany -Fonblanque was dead. He had so dropped out of sight that few knew him to be living. His name was famous forty years ago, and his political essays are still quoted by elderly gentlemen as tokens of the brilliant intellect which reigned over politics when Brougham, Sydney Smith, and Macaulay made the Edinburgh Review sparkle with satire, wit, or declamation ; when Canning lifted squibs into the dignity of Parliamentary powder and shot ; when the dullest of country gentlemen could round a peroration with an apt line from Horace ; and when the hues of literature were so shot through the web and woof of politics that the classics went into the division lobby with the Tories or the Whigs. But Fonblanque suddenly fell as much out of sight as if a trap-door had opened on the stage, and he had sunk into the abyss which underlies the painted gaiety of existence. He had gone down among figures, and was to spend his wit on the super- vision of statistical tables at the Board of Trade. It seemed as sad a fate as that of Horace would have been if he had been set to keep the accounts of the Imperial kitchen ; and, at least, Fon- blanque never came up to the daylight again. We believe that he did write many articles after he was tied down to the gin- horse round of the multiplication.table ; but either they lacked the old fire, or the sparks were struck forth too fit- fully to win much notice ; for no one spoke of Albany Fonblanque any more, and he was as if he were dead. The brilliant wit, the master of classic English, the most deft wielder of sarcasm known to. our fathers, became a mere Govern- ment official, doing such work as any average City man could compass. He became a statistical prisoner of Chillon, forgotten by the world, yet, it would seem, so fond of his dungeon and his chains at last, that he would not again leave the gloom for the daylight of literature. Quitting journalism at the early age of thirty-eight, he seems to have wilfully cancelled thirty-seven years of literary possibility, and to have locked up all the treasures of his bright brain in much the same fashion as the late Lord Hertford bid away, in an old house in Paris, the pictures which are now delighting all of us at Bethnal Green. We hardly dare to hope that Fonblanque has also left treasures to a benevolent Sir Richard Wallace, and that we have yet to see the hoarded fancies of the brilliant writer.

Albany Fonblanque began to write at a time when such wit and such satire as his seemed to have a field specially fashioned to draw forth their full powers. The Church was a pet preserve of place-hunters, and of men who sought to enter into heaven by the gate of Greek. A bishop died leaving /400,000. The prelates seemed most devoutly earnest when wrangling with each other or with the Ministry as to the best way of fleec- ing their flocks. Half the boroughs of England were rotten. Boroughmongering had reached the dignity of a learned profession. Peers put forth the claim to drive their tenants to the poll with the same calm, unblushing vigour as they now insist that the country shall keep up a special set of Game laws to give them and all other rich men what they call "sport." August personages did immoral deeds as publicly as august personages now shoot pigeons or dip their hands in the blood which is shed at battues. The spirit of Toryism—or, in other words, the spirit which fancies the earth to have been made for the special benefit of a select few, with power to add to their number—had drawn new vigour from the destruction which had come upon the practical creed of the French Revolution, and it spoke insolently and high, as if it fancied that the earth was the Peers' and the fullness thereof. There were, it is true, no lack of censors to rebuke the insolence of purse and rank. The Edinburgh Review struck hard within the limits of a sublime Whiggery,—so hard that an irascible old gentleman has been known to kick

a copy of the periodical down-stairs because he had been enraged by some violent philippic of Brougham's ; and the witty satire which Sydney Smith flung at such atrocities as man-traps, or such irritating follies as the penal laws against the Catholics, have now passed into the literature of polemics.

But the Edinburgh was careful to free itself from the reproach

that it wrote with the pen of Radicalism, and the vigour of Macaulay blossomed into arrogance when he smote that Benthamite sect which found Whiggery to be only one degree less tolerable than Toryism. Radicalism had, it is true, a score of able pens. Cobbett wrote with a vigour, a homely plainness, a rich and racy freshness of imagery such as we find in the speech of unlettered wits who have been mentally fed on proverbs and local stories that have never been diluted with the general-

ities of print. Everybody read the Political Register, or the Twopenny Trash. The very clodhoppers read it, because Cob- bett took the trouble to make politics plain by never assuming

that his readers knew anything, and by anticipating, with a marvellous dramatic instinct, the difficulties which would spring up in the struggling mind of unlettered readers. But Cobbett was too coarse, too ignorant, too blind to the truth of what was said by his foes, and too much of an old soldier with a gift for writing good English, to do Radicalism any service among cultivated people. He rather deepened the idea that Radicalism was so essentially vulgar as to be a fitting creed only for men who did not go into society. Nor did the Benthamites do much to take away the reproach, for they spoke a Babylonish dialect which only those brethren who had the gift of prophecy could interpret. They were so much the slaves of system that they could not build a hut until they had raiseda frame-work of scaffolding which would have served for the construction of a cathedral. Plain men were scared by a jargon as uncouth as that which came from the followers of Lady Hunting- don, or from Ranters who were going through the process of con- version. The Benthamites failed to win the ear of the world be- cause they were a sect. They needed an interpreter who could translate the phrases of the brotherhood into the language of good society, who could write such English as should merit the homage of literary students, and who could pour forth a wit that was nob far short of the luxuriant richness of jest that flowed unbidden from the pen of Sydney Smith. Such was Fonblanque.

Although he had no such original faculty as Bentham, James Mill, or Grote, he had the gift which stands next in value, for he displayed a remarkable power of mastering the thoughts of such men, and giving them a popular dress, without taking away any part of their logical rigour. The study of philosophy, law, and politics had filled his mind with those hard facts which are to thought what rails are to locomotive steam-engines. And he had a further capacity for political writing in the fact that he was a good hater. Ho hated the Tories, especially the Boroughmongers and the Bishops. He hated the inequalities of the laws, the big incomes of the pre- lates, the pluralities of the clergy, and above all things, the cant of the pulpit, which, at the bidding of ten thousand a year, taught that it was easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the Kingdom of Heaven. We suspect that he despised the whole fabric of the British Constitu- tion, and especially the political fictions in which popular fancy sees the crown of human wisdom, although even he did not dare to give voice to such sedition at a time when the Press had not yet freed itself from the leading-strings of judicial caprice. His Radicalism went far deeper and farther afield than that of Cobbett, which indeed was curiously mixed with Toryism, and seemed to have been built of the thoughts, facts, prejudices, tastes, or likings that had come first to hand, so that a geologist would have described it as a bit of conglomerate rock. Fon- blanque's Radicalism went deeper because it had been cut out with a philosophical knife, which was too keen to spare the sanctities of the Select Vestry or the Rubric. It would have frightened or disgusted society if it had been laid bare ; but Fonblanque took care that it should always be veiled in the flowers of litera- ture, fancy, and wit. In reality, he was drawing the English people to what they would have deemed an abyss if he had laid the chasm bare, but he hid the opening with foliage. He had roamed over the literature, and especially the literature of fiction, with a keen eye for whatever was full of humour or satire, with a memory that forgot nothing, and with a marvellous power of using the spoils of such literary forays to illustrate the wickedness of Tories, Bishops, Boroughmongers, and game-preservers. Nowhere else do we find such amazing aptness and readiness of humorous and sarcastic citation. Even Macaulay, although an incomparably greater writer, does not equal Fonblanque in the power of laying his pen on the very bit of fiction, fable, or song that will best do the work of reasoning, denunciation, or ridicule. The brilliant Radical, in fact, tried to hide the reasoning process as carefully from his readers as a nurse smothers a nauseous potion in jelly before giving it to a sick child. He never would unbare a syllogism if he could tell a story. As we go over the three volumes of his leading articles, we knock at every turn of the way against Fielding, Smollett, Swift, Sinbad the Sailor, the pro- phets Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Daniel, Hosea, and half the host of Israel. He made them all contributors to the Examiner. Thus his political writing is more like what we see in the time of Dryden or Addison than the hard and practical comments of our own day. His model had manifestly been such books as " Absolom and Achitophel." He was less eager to give the keen and cutting reasoning of his master Bentham than to copy such brilliant satire as the portraits of Lord Shaftesbury, the Duke of Backingham, and Slingsby Bethel. He seldom ventured to give a long disquisition on Parliamentary Reform, vote by Ballot, or any other of the questions which perplexed our fathers ; his usual practice being to seize au unlucky politician who has said something with which he did not happen to agree, and put him in the pillory. The favourite objects of his satire were Eldon, Peroeval, the Duke of Welling- ton, Cumming, and the Bishops. And his whip-band was weakened by no feeling of decorum. Neither Dryden, Swift, Churchhill, Junius, nor Cobbett ever hit with more fury than Fonblanque, although the light tone of his satire usually robs it of malignity. He tells us that George IV. presented a vase to Lord Eldon when the old Tory Chancellor retired into private life with the spoils of his long industry. Hating Eldon with a humorous ferocity, he reminds the King that when the Old Man of the Island relaxed his grip on Sinbad in a moment of intoxication, Sinbad did not show his regard for the treacherous old gentleman by giving him a vase, but took up a stone and very discreetly beat his brains out, lest he should betray more men. Again, Perceval, whose sanctity was as loud as his Toryism, had persuaded the Ministry to promise that it would order the nation to observe a general fast. This act disgusted Fonblanque to the depths of his soul, and he poured on Perceval such a flood of witty contempt as the freest of journals would not dare to direct against the vilest of public men in these days of decorum. Mr. Perceval is saluted as the Member for Heaven ; but he shows signs of differing from his constituency. He had quoted Scripture, and the satirist turns round with the question whether the Scripture says anything about Pharisees, who pray and boast their piety aloud, and rate the pub- licans; or about pensions, Dives and Lazarus, the soul-destroying effects of riches ; or about bribery and corruption, lying, slander- ing, evil-speaking, and taking the Lord's name in vain. "Does the Scripture," he adds, "say, Out uponye, ye hypocrites?" Fon- blanque contends he has a right to call Perceval a "worm," for according to the Scripture man is a worm, and it is clear that Perceval is the worm that eats the substance of the people, the worm that never dies in the public pocket. And then follows a long extract from the Book of Samuel, to show that when the prophet warned the Israelites against the woe which would come upon them if they should take a King, he had in view such beings as Perceval and the Boroughmongers, the true harpies, the obscene creatures, that befoul whatever they touch with "their rapacity and corruption, their robbing, ravening, rioting, and tainting." It was a favourite device of Fonblanque to reprint whole chapters of the Bible in order to millet the Prophets on the side of the Radicals, and to borrow the light- nings of Heaven to smite the Tories. He found the weapon specially effective against the Bishops. Those dignitaries, he insisted, should accept the literal meaning of the Scriptural assur- ance that it was more easy for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter into the Kingdom of Heaven. And he maliciously suggested that by drawing their thousands a year they deliberately intended to take on themselves the burden both of wealth and of damnation, in order that their flocks might be at once poor and fitted for bliss. With striking force of malignity, and in words which admirably reproduce the simplicity and picturesque hues of the Biblical style, the sarcasm was un- folded in "A Fragment from the First Book of Judas," which gives a letter that the Apostle of the Purse wrote to Simon Magus. The Liberation Society never penned such a satire against the Church, and never indeed commanded a pen of the requisite keenness for such a task. Nor did Fonblanque disdain the resources which are now left to Punch when he wanted to fling a stone at his political foes. He once gave a list of derivations from a dictionary of antiquities which should be published in the year 2793, and each was a political sarcasm. Thus the word " Duties " was given as a synomym for the word "Taxes." "Hence," adds the anticipated dictionary, "in the time of the Boroughmongers, we see the phrase 'His Majesty's dutiful subjects.'. A book was writ-. ten entitled the Whole Duty of Man.' It treated of Taxa- tion in all its branches." Again, the word " Parliament " is a compound from the French of parler, to speak, and mentir, to lie. Hence truth was called un-Parliamentary language." Despite the ferocity of the satire, the Examiner was read by all cultivated men, and even, we have no doubt, by the Bishops themselves, on account of the brilliancy with which it was written. The blackest victims of Fonblanque's wit must have drawn some joy from the fact that they were damned in admirable English.

Although Fonblanque wrote in a time when class-selfishness and the blindness of the lawmakers had stirred even the apathetic English to the edge of revolt, not a tone of sadness or pathos rings through his writings. Sarcasm, wit, and denunciation meet us everywhere; but the tone is light and almost gag, as if he found a delight in lashing the Boroughmongers and the fat Bishops, apart from the wish for the destruction of the abuses which they represented. That he was deeply in earnest, we have

no doubt ; but his writings often wear a trifling air, when com- pared with the graver essays which the public demand in these days. And they strangely lack the solid instruction which is now given in the daily and weekly Press. Elaborate statements of fact are wholly missing. The essays bear the same relation to the political writing of our own time that the rhetorical speeches which were once deemed the gems of Parliamentary oratory bear to the matter-of-fact harangues which, thanks to the prosaic spirit exemplified by Peel and Cobden, are now the most effective of political appeals. Fonblanque would have written with more gravity, more weight of matter, and we fear that we must add with more dulness, if he had addressed this generation. He has left no legacy of thought, and at best he is only a political satirist. But he has scarcely a rival in his own way ; and the pure and masculine English, the wit, the sarcasm, the brilliant invective, in which Fonblanque clothed his scorn of the iniquities, the falsehoods, and the cruelties that once stained our political life, will draw the student to "England Under Seven Administrations " long after the questions of which the book treats shall have ceased to be charged with a living interest.

Previous page

Previous page