ARTS

In architecture, as in many other areas of culture, to be characterised as typically English would normally be construed as an insult. There is nothing new about this. It has been going on without a break since the Renaissance. The result is that English- ness can only be understood by including in it a self-criticism which frequently amounts to self-hatred. In our cultural hall of smoke and mirrors, we try not to look at our- selves, with the result that our lack of clear vision equally incapacitates us when trying to look at other nations and their achieve- ments, tending to overvalue them or at least misunderstand them.

There are many stories of foreign archi- tects visiting London and admiring the buildings we most wish to conceal because we are ashamed of their Englishness. French 18th-century classicists admired St Paul's, when the English Palladians had condemned it. Le Corbusier thought very highly of Welwyn Garden City, at a time when his followers were building massive slab blocks, and the Italian Rationalist, Aldo Rossi, had eyes only for Vincent Har- ris's 1950s Ministry of Defence Building in Whitehall, with its austere Portland stone elevations and little rooftop pavilions, a building which has been excluded from the canon of architectural history.

The legacy of this confusion is apparent in contemporary architecture and acts as a limitation on its otherwise flourishing con- dition. It is particularly relevant to the idea of Modernism, which, it has always been assumed, is a product only available as an import and identifiable by its foreign-language labels and delightfully exotic flavour. Pierre Bor- dieu's concept of Cultural Capital well describes the mystique of Modernism. To have this thing, you have to be a special person, and having it confers specialness on you. It is the equivalent of a trophy souvenir from a foreign holiday. If everyone had it, it would no longer be special, and neither would you.

The irony of treating Modernism this way is that its declared purpose is to be available to everyone. Two conceptual fallacies seem therefore to result from this irreconcilable position. First, if Modernism were to become assimilated and no longer foreign (the equivalent, perhaps, of Brie made in Somerset, which, as everyone knows, is probably better than the French product), it automatically ceases to be authentically modern. As far as the consumer is con- cerned, this is irrelevant, but the con- sumer's voice in architecture is scarcely ever heard in the professional dis-

A lack of clear vision

Alan Powers on why we should not be ashamed of the Englishness of our buildings

course, and usually only when it has become identical to the plaintive and injured voice of the producer.

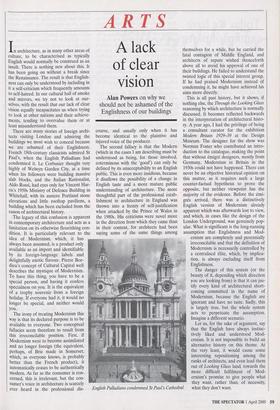

The second fallacy is that the Modern (which in the cases I am describing must be understood as being, for those involved, coterminous with the 'good') can only be defined by its unacceptability to an English public. This is even more insidious, because it disallows the possibility of a change in English taste and a more mature public understanding of architecture. The more thoughtful part of the professional estab- lishment in architecture in England was thrown into a frenzy of self-justification when attacked by the Prince of Wales in the 1980s. His criticisms were novel more in the direction from which they came than in their content, for architects had been saying some of the same things among English Palladians condemned St Paul's Cathedral themselves for a while, but he carried the fatal contagion of Middle England, and architects of repute wished thenceforth above all to avoid his approval of one of their buildings. He failed to understand the twisted logic of this special interest group. If he had praised Modernism instead of condemning it, he might have achieved his aims more directly.

This is all past history, but it shows, if nothing else, the Through the Looking Glass reasoning by which architecture is normally discussed. It becomes reflected backwards in the interpretation of architectural histo- ry. A year ago, I had the privilege of being a consultant curator for the exhibition Modern Britain 1929-39 at the Design Museum. The designer for the show was Norman Foster who contributed an intro- duction to the catalogue, making the point that without émigré designers, mostly from Germany, Modernism in Britain in the 1930s could not have happened. There can never be an objective historical opinion on this matter, as it requires such a large counter-factual hypothesis to prove the opposite, but neither viewpoint has the majority of the evidence. Before the émi- grés arrived, there was a distinctively English version of Modernism already apparent which was afterwards lost to view, and which, in cases like the design of the London Underground, was genuinely pop- ular. What is significant is the long-running assumption that Englishness and Mod- ernism are completely and perennially irreconcilable and that the definition of Modernism is necessarily controlled by a centralised elite, which, by implica- tion, is always excluding itself from Englishness.

The danger of this system (or the beauty of it, depending which direction you are looking from) is that it can jus- tify every kind of architectural short- coming committed in the name of Modernism, because the English are ignorant and have no taste. Sadly, this is largely true, but the whole system acts to perpetuate the assumption. Imagine a different scenario.

Let us, for the sake of argument, say that the English have always instinc- tively liked and understood Mod- ernism. It is not impossible to build an alternative history on this theme. At the very least, it would cause some interesting repositioning among the ranks of architects, and even lead them out of Looking Glass land, towards the more difficult fulfilment of Mod- ernism's promise to give people what they want, rather than, of necessity, what they don't want.

Previous page

Previous page