Theatre

Les Miserables (Royal Albert Hall)

Lucky Sods (Hampstead) Funny Money (Playhouse) Oliver!

(London Palladium) The Meteoric Rise and Dramatic Demise of Edmund Kean Tragedian (King's Head)

Glory of the glums

Sheridan Morley

Writing the Punch theatre column exactly ten years ago this week, I noted that I had just seen the musical of my lifetime thus far. I believed it would stand out as the greatest of this half-century, just as Porgy and Bess stood out for the first 50 years of it. It was not at the time a popular view: colleagues told me I had taken leave of such critical faculties as I'd ever pos- sessed, and that Les Miserables would merely join a long list of disastrous attempts by our subsidised companies (it was then at the RSC's Barbican) to join the Broadway bandwagon.

A decade later, watching on Sunday night at the Royal Albert Hall as a cast of 500 from all the worldwide productions of Les Miserables celebrated its tenth anniver- sary in front of a cheering crowd of 5,000, it was good to see Victor still victorious. Hugo himself had received terrible reviews when his book first came out. In the 1840s as in the 1980s, the only people who liked Les Miserables were the public. Watching an international parade of Jean Valjeans from 16 countries where the show has tri- umphed in front of 40 million people, should remind those who still believe the RSC should not do musicals that without the ten million pounds that company alone has made from Les Mis, it would not still be in existence.

The greatness of Les Mis, as Sunday's concert performance yet again established, is that (like Peter Grimes and Rigoletto and Sweeney Todd but not much else), it lives on the borderlines where music theatre is redefined. This is not the French Oliver! nor yet the musical Nicholas Nickelby, though it owes a certain debt to both. It blasts epic French history across the barri- cades of its revolutions, channelling a nation's history through trumpets and drums; it is dangerous and brilliant and just the best. Still.

The return of Terry Johnson's award- winning Dead Funny to the Savoy has made other new comedies of the season look curiously of another era. John Godber's Lucky Sods (at Hampstead) is a desperately thin and repetitive account of a married couple for whom money proves unable, surprise surprise, to buy happiness. She buys the lottery ticket, he chooses the num- bers, they win four million pounds, he proves unfaithful and she dies. That is about it, across two hours, except for some minor characters who can only be given any real interest by having the same two actors play six of them. Godber and his Hull Truck players have cornered the regional market in no-frills touring with minimal sets and casts, but at Hampstead they look desperately under-nourished, as does the play.

Better news at the Playhouse, where Ray Cooney has brought together some vintage farce players (Henry McGee, Charlie Drake, Trevor Bannister) for his own Funny Money, which again concerns a man with a windfall — in this case £750,000 when he picks up the wrong case at a rail- way station. What to do with the cash then becomes the excuse for a succession of classic farce confrontations with the forces of the law, as represented by wives and policeman. Cooney himself, as star, author and director, is now the sole heir in this country to Brian Rix, and the Ben Travers team before that. But as a comic figure he is at his best having things happen to him rather than, as here, having to engineer the plot and drive it forward: a natural stooge, he seems in need of a partner. For all that, this is a mechanical masterpiece of manu- factured mirth; just don't expect to relate to it. While Johnson has established that you can be made to care about people in a farce, Cooney and Godber still just want us to laugh at them.

At the London Palladium, in his first return to the London stage from Broadway in 20 years, Jim Dale has now replaced Jonathan Pryce as Fagin in Lionel Bart's Oliver! An acrobatic and hugely likeable entertainer, he suggests the leader of a troupe of child street-entertainers rather than the evil old Jew of the Dickens novel, but that is a recurrent problem in the days since the Alec Guinness movie was seen in political correctness to be anti-Semitic. The truth is that we can't accept the full Fagin nowadays, and even if we could he would look out of place in a Palladium extrava- ganza which has abandoned the old Sean Kenny/Ron Moody chamber-drama with songs in favour of a lavish spectacular owing more to the wide-screen movie of the 1960s than the black-and-white classic of the 1940s.

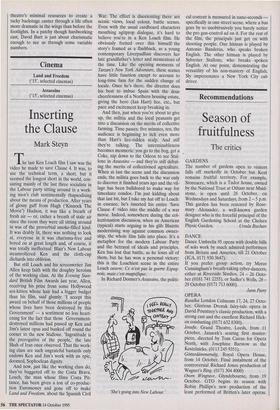

And still on musicals, at the King's Head, Sylvia Freedman and Michael Jeffrey have an inventive, small-scale biography of Edmund Kean which makes a virtue of that theatre's minimal resources to create a tacky backstage canter through a life often more dramatic in the wings than before the footlights. In a patchy though hardworking cast, David Burt is just about charismatic enough to see us through some variable numbers.

Previous page

Previous page