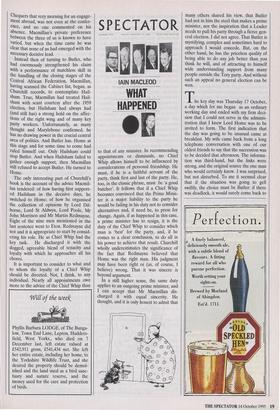

A QUESTION OF LOYALTY

Lord Home, the former Prime Minister; died

this week. We reprint lain Macleod's expose

of how Home was handed the keys to No 10

In October 1963 Harold Macmillan's manoeuvrings ensured that Lord Home, rather than Rab Butler, succeeded him as Conservative leader and Prime Minister. lain Macleod instantly resigned as Chairman of the Conservative Party and Leader of the House of Commons. Soon afterwards, he became editor of The Spectator. When, in January 1964, Randolph Churchill published an account of the Tory leadership crisis favourable to Macmillan, Macleod finally broke his silence in the guise of a book review, which laid bare the political chi- canery behind the Tory party's 'magic circle' system of selecting its leader.

The effect was devastating, and, as this week's Times obituary notes, 'convinced Home that no succeeding Conservative lead- er should ever be put in the position where his claim to office was questioned by his party.' Therefore, after his defeat in the 1964 general election, Home provided a system for electing future leaders of the Party by all Conservative MPs. It is a system, which, with some modifications, survives to this day, and which John Major most recently invoked to reassert his legitimacy as Tory leader.

UNTIL Mr Randolph Churchill's book The Fight for the Tory Leadership appeared, there had been an unspoken agreement that the less said about the recent struggle for the Tory leadership the better. 'Macleod and Powell,' wrote a polit- ical commentator, 'have been reticent to a tactical fault.' The Prime Minister went out of his way to be uncommunicative on tele- vision and in his press interviews. With the exception of an intervention by Martin Redmayne, the Chief Whip, to which I refer later, little or nothing was said. Spec- ulation, of course, was feverish, but with lit- tle to feed on soon died. The scars healed swiftly.

The attractive feature of the book is Churchill's enduring loyalty to and affec- tion for Harold Macmillan. This flowers on the last page `. . . the magnificent and hero- ic service — his last great service — that Mr Macmillan rendered to the monarchy, the nation and the Tory party. From his sick bed, at the risk of his life . . .' Churchill knows well (and acknowledges more than once in the book) that I share the loyalty and affection that he has for Macmillan. I was, I think, at the end perhaps the only member of Macmillan's Cabinet to hold steadily to the view that the Tory party would do better under Macmillan's leader- ship at the polls than they would under any of the possible alternatives. Both of them then must know how much I would like to underwrite Churchill's conclusion in full. I cannot. And in so far as I can subscribe to the theory that Macmillan performed a sig- nal service to the Tory party, I can only do it by rejecting the basic assumptions of the book and arguing from the one premise that seems to me to offer a logical, defensi- ble, and indeed honourable explanation of what happened.

Churchill writes: 'It can be argued that Macmillan did all he could during his seven years as Prime Minister to advance the for- tunes of Butler.' Almost anything can no doubt be argued, but no one close to poli- tics or to Harold Macmillan could seriously support this suggestion for a moment. The truth is that at all times, from the first day of his premiership to the last, Macmillan was determined that Butler, although incomparably the best qualified of the con- tenders, should not succeed him. Once this is accepted, all Macmillan's actions become at least explicable. He thought that three of the members of his Cabinet who were in the House of Commons, apart from Butler, were papabile and of sufficient seniority to be considered: Maudling, Heath and myself. It was not by accident that he brought forward these three respectively to be Chancellor of the Exchequer, minister in charge of our bid to enter the Common Market, Chairman of the Party and Leader of the House of Commons. He planned this and hoped that one of the three would show himself clearly as the future leader. It was not by accident that the three sessions of the much publicised and somewhat pointless planning weekend at Chequers on the modernisation of Britain were presided over by the same three. Home, who left Chequers that very morning for an engage- ment abroad, was not even at the confer- ence, and no one commented on his absence. Macmillan's private preference between the three of us is known to have varied, but when the time came he was clear that none of us had emerged with the necessary decisive lead.

Instead then of turning to Butler, who had enormously strengthened his claim with a performance of matchless skill in the handling of the closing stages of the Central African Federation, Macmillan, having scanned the Cabinet list, began, as Churchill records, to contemplate Hail- sham. True, Macmillan had treated Hail- sham with scant courtesy after the 1959 election, but Hailsham had always had (and still has) a strong hold on the affec- tions of the right wing and of many key party workers. Unfortunately, as many thought and Marylebone confirmed, he has no drawing power in the crucial central area of politics. And Butler has. Home at this stage and for some time to come had ruled himself out. Only Hailsham could stop Butler. And when Hailsham failed to gather enough support, then Macmillan still refused to accept Butler. He turned to Home.

The only interesting part of Churchill's book is the account of the advice Macmil- lan tendered: of how having first support- ed Hailsham in the decisive days, he switched to Home; of how he organised the collection of opinions by Lord Dil- home, Lord St Aldwyn, Lord Poole, Mr John Morrison and Mr Martin Redmayne. Eight of the nine men mentioned in the last sentence went to Eton. Redmayne did not and it is appropriate to start by consid- ering his role. He as Chief Whip had the key task. He discharged it with the dogged, agreeable blend of tenacity and loyalty with which he approaches all his chores.

It is important to consider to what and to whom the loyalty of a Chief Whip should be directed. Not, I think, to any individual. Nearly all appointments owe more to the advice of the Chief Whip than to that of any minister. In recommending appointments or dismissals, no Chief Whip allows himself to be influenced by considerations of personal friendship. He must, if he is a faithful servant of the party, think first and last of the party. He, too, in the classic phrase, must be 'a good butcher'. It follows that if a Chief Whip becomes convinced that the Prime Minis- ter is a major liability to the party he would be failing in his duty not to consider alternatives and, if need be, to press for change. Again, if as happened in this case, a prime minister has to resign, it is the duty of the Chief Whip to consider which man is 'best' for the party, and, if he comes to a clear conclusion, to do all in his power to achieve that result. Churchill wholly underestimates the significance of the fact that Redmayne believed that Home was the right man. His judgment may have been right or (as, of course, I believe) wrong. That it was sincere is beyond argument.

In a still higher sense, the same duty applies to an outgoing prime minister, and I can accept that Mr Macmillan dis- charged it with equal sincerity. He thought, and it is only honest to admit that many others shared his view, that Butler had not in him the steel that makes a prime minister, nor the inspiration that a Leader needs to pull his party through a fierce gen- eral election. I did not agree. That Butler is mystifying, complex and sometimes hard to approach I would concede. But, on the other hand, he has the priceless quality of being able to do any job better than you think he will, and of attracting to himself wide understanding support from many people outside the Tory party. And without such an appeal no general election can be won.

The key day was Thursday 17 October, a day which for me began as an ordinary working day and ended with my firm deci- sion that I could not serve in the adminis- tration that I knew Lord Home was to be invited to form. The first indication that the day was going to be unusual came at breakfast. My wife came back from a long telephone conversation with one of our oldest friends to say that the succession was to be decided that afternoon. The informa- tion was third-hand, but the links were strong, and the original source the one man who would certainly know. I was surprised, but not disturbed. To me it seemed clear that if the situation was going to gell swiftly, the choice must be Butler: if there was deadlock, it would surely come back to the Cabinet. I had not, of course, appreci- ated then that it was in fact an essential part of the design that the Cabinet should have no such opportunity. Churchill's book makes this plain.

My only important engagement in the morning was a meeting at No 10 called by Butler to consider the difficult closing stage of the Kenya conference. Both Maudling and I attended as ex-Secretaries of State for the Colonies. I walked away with Maudling to his rooms at the Trea- sury. I had always held Maudling in high and warm regard and throughout consid- ered him a possible prime minister. Alone in the Chancellor's room over a drink I told him of my wife's telephone conversa- tion. He had heard nothing, and had in general reached a similar conclusion to mine. Naturally his own chances (which he recognised were now slim) depended on the issue being protracted. A decision today, he thought, could only be for But- ler. And with this he was more than con- tent. He spoke on the telephone to Lord Dilhorne, and the Lord Chancellor con- firmed that he and others were to present their collective views that afternoon. They had already been separately to see Macmillan that morning. To all sugges- tions that the Cabinet (or the Cabinet less the chief contenders) should meet, Dil- home was deaf; as he had been, I have since learned, to at least one more similar request. No doubt he thought he was act- ing wisely.

Curiouser and curiouser it seemed, and Maudling and I decided to stay in touch. I joined him and Mrs Maudling for lunch. Butler was discussed a good deal. Hail- sham we mentioned once, but we both knew that his bandwagon had long ago stopped rolling; indeed, the opposition to Hailsham (not, of course, on personal grounds) was and was known to be so formidable that it remains astonishing that he was not given clear warning of it in advance of his declaration that he would disclaim his peerage. Home we never mentioned in any connection. Neither of us thought he was a contender, although for a brief moment his star seemed to have flared at Blackpool. It is some measure of the tightness of the magic circle on this occasion that neither the Chancellor of the Exchequer nor the leader of the House of Commons had any inkling of what was happening.

After lunch I returned to the Central Office to clear some papers. In mid-after- noon the telephone rang. It was an impor- tant figure in Fleet Street. He told me the decision had been made, and that it was for Home. He himself found this incredi- ble, but he was utterly sure of his source. I telephoned Maudling and Powell and arranged to meet as soon as we could at my flat. Powell's views, I knew, coincided with mine and both at Blackpool and in the days following the conference we had been closely in touch. Almost at once the phone calls started from the leading news- paper political correspondents. Each of them had the same story. Someone, I pre- sume, thought it proper even before the Prime Minister had resigned to prepare the press for the (unexpected) name that was to emerge. News management can be taken too far.

Before, however, any action could be contemplated, the story had to be con- firmed beyond doubt. Maudling thought he knew someone who could clear this up, and he left us for half an hour. He telephoned back with confirmation and rejoined us, as did another member of the Cabinet. Lord Aldington also came to my flat and joined in our discussions. Meanwhile the stream of telephone calls from the press contin- ued.

If we were going to make any serious protest against an invitation being extend- ed to Lord Home, it was essential that he should know know about this at the earliest moment. Powell and I each decided to speak to him direct. I had a dinner engage- ment myself, but telephoned Lord Home, who was out, and made an appointment for Powell and myself to see him after dinner.

From the beginning I was in no doubt that if as joint Chairman of the Party and Leader of the House of Commons, I felt strongly enough to tell Lord Home that I thought it wrong for him to accept an invi- tation to form an administration, I could not honourably serve with him in that administration. I slipped away for a moment to find my wife in her room. I told her what I thought the end might be, and yet that I felt clear that in the true interests of the Tory party another point of view must be put. She agreed with me at once My only consolation is that by eating us, they're killing themselves.' and has continued to back my decision through all the unpleasantness, local and national, that we knew we must face. Then my wife and I went off to the Political Committee's Dinner of the St Stephen's Club, where I made as gay and confident a speech as I could. After the dinner I tele- phoned Powell and went round to his house in South Eaton Place. When we telephoned Lord Home from there it was apparent that we could not see him with- out running the gauntlet of the reporters who had already encased him. So we spoke on the telephone.

I spoke first. I told him that there was no one in the party for whom I had more admiration and respect; that if he had been in the House of Commons he could perhaps have been the first choice; but I felt that those giving advice had grossly underestimated the difficulties of present- ing the situation in a convincing way to the modern Tory party. Unlike Hailsham, he was not a reluctant peer, and we were now proposing to admit that after 12 years of Tory government no one amongst the 363 members of the party in the House of Commons was acceptable as prime minis- ter. I felt it more straightforward to put these views to him tonight rather than per- haps have to put them in other circum- stances tomorrow.

I did not hear what Powell said to Lord Home, but I believe that he spoke to him on similar lines.

One by one the others, Maudling, Ald- ington and Erroll, joined us at Powell's house after their evening engagements. Thus came about the famous 'midnight' meeting. Churchill falls into the common error of assuming that only those events that were recorded happened. In fact, there were to my knowledge three meet- ings of ministers that evening and there may well have been others. The reason this one was discovered was that Henry Fairlie, on telephoning the home of one of those attending it, was given a second number to try. This he traced as Enoch Powell's.

Shortly before Powell and I spoke to Lord Home, Hailsham had telephoned, having heard the report of the intended nomination of Lord Home, and he remained in close touch with one or other of those present during the rest of the evening. Before long it was established that Maudling and Hailsham were not only opposed to Lord Home but believed But- ler to be the right and obvious successor and would be ready and indeed happy to serve under him. The rest of us felt this understanding between those hitherto the three principal contenders was of decisive importance: the succession was resolving itself in the right way. We telephoned the Chief Whip who, rather than embark on a lengthy discussion over the line, decided to join us. He naturally did everything he could to persuade us to accept the situa- tion as he saw it, but we finally asked him to report to the Prime Minister the fact of the understanding which had arisen between Butler, Maudling and Hailsham. He promised to do this. Before the meeting ended, Powell and I, with Maudling, spoke to Butler himself, told him what had been agreed, and assured him of our support.

Next morning, Churchill discovers a new ' "Stop Home" movement, this time organ- ised by Hailsham'. He is wrong. Hailsham didn't arrange the meeting between Butler, Maudling and Hailsham. I did. It is not true that `Maudling failed to rally to But- ler'. The meeting in effect was the logical outcome of what had happened the previ- ous night.

But events were moving fast. Macmillan rallied Lord Home with the curious obser- vation: 'Look, we can't change our view now. All the troops are on the starting line. Everything is arranged . . sent his letter of resignation to the Palace, and the same morning tendered advice to the Queen in the form of a memorandum which we are told incorporated all the four reports which Macmillan had asked for. So Churchill has it and his source should know. The memo- randum then purported to be not the advice of one man, but the collective view of a party. There is no criticism whatever that can be made of the part played by the Crown. Presented with such a document, it was unthinkable even to consider asking for a second opinion. Nevertheless, the procedure which had been adopted opens up big issues for decision in the future. That everything was done in good faith I do not doubt — indeed, it is the theme of this review to demonstrate it — but the result of the methods used was contradic- tion and misrepresentation. I do not think it is a precedent which will be followed.

When Lord Home was sent for by the Queen and began inquiries to see whether he could form a government if he accepted her commission, Maudling and Hailsham kept to their agreement with Butler and declined to serve unless Butler did. Butler himself reserved his position, intimating that he would not serve under Lord Home unless satisfied that it was 'the only way to unite the party'. At this stage at least two members of the old Cabinet besides myself — Powell was one of them — who knew what the situation was used their influence towards what they believed the right solu- tion by answering Lord Home's inquiry in the negative. When, in the event, Butler decided to serve and Lord Home's govern- ment was formed, Powell thought it right to stand by the answer he had given.

I myself had two short interviews with Lord Home, one before and one after he became prime minister. Both were very friendly but brief. I am sure he would have liked me to change my mind. I like to think that he knew that I could not. For myself and for Powell it had become a matter of `personal moral integrity'. The words are those of another member of the Cabinet.

When then did Home emerge as a contender? Hindsight is invaluable for politicians. People assure me now that `everyone' knew for days or weeks or even years. In fact, the Cabinet left for Black- pool assured that Home was not a con- tender and that (if Macmillan's health failed) Hailsham probably was. On the Thursday I appeared on television with David Butler and listened to his appraisal of the contenders' chances. When he asked me afterwards (off screen) for comment, I said that it was a fine analysis and only obviously wrong in one assessment. I promised to tell him 'when all this is over' what was wrong. Lunching with him recently, I explained my comment. Home, I told him, was at the time of the broad- cast in no circumstances a contender. Nor, in spite of his own hedging television appearance, can he have been when he spoke on Friday to the National Union. Nor do I believe that to the mass meeting on Saturday he could have used these words, 'We choose our leader not for what he does at a party conference but because the leader we choose is in every respect the whole man who is fit to lead the nation,' if his own hat was already in the ring. On the Tuesday following Blackpool a member of the Cabinet came to see me. He had been trying without success to have a meeting of the Cabinet called to consider the situation. I gave him splen- didly ironical advice in the light of what was already afoot. 'Try Alec,' I said, 'he's not a contender, and he ought to be a kingmaker.' He took my advice, but not surprisingly without result.

Although I am sure his friends were urg- ing him to declare himself earlier, the explanation that seems least in conflict with the known facts is that some time on Sunday or Monday — anyway, post-Black- pool — Lord Home began to organise his position.

On Friday, 25 October, timing his speech to coincide with the opening of the Kinross campaign, the Chief Whip at Bournemouth set out to show that Lord Home was not a compromise candidate. Churchill (or rather Macmillan), by seek- ing to extend the argument to the other three groups, brings the whole structure down in an absurd, even laughable welter of confusion. Home had formidable sup- port. Much better to leave it at that. Any successful contender would have been a compromise selection. The account in Churchill's book therefore cannot be allowed to stand as history.

Redmayne said, and added, very proper- ly, that some people would criticise him for revealing information given in confi- dence, that even on the first preferences Home had a very small lead. I am neither impressed nor surprised. The Chief Whip had been working hard for a week to secure the maximum support for Lord Home. So, quite properly, had several of the leading figures of the back benches. That in such circumstances Lord Home achieved a majority of one or perhaps two will amaze few people. And if the record- ing of opinions approached the confusion known to have been engendered by the method of sounding the Cabinet, the mar- gins of error must have been enormous. On the Third Programme Redmayne, after repeating this, went further. He said, 'The various sources of advice in greater or less degree came to the same conclusion.' One can at least be confident that this was so for the House of Lords. Churchill records: `St Aldvvyn was able to report that the peers were overwhelmingly for Home.' I'm sure they were. It reminds me of the verse composed as an epitaph for Tom Harrisson who with Madge founded Mass Observa- tion — Dr Gallup's forefather:

They buried poor Tom Harrisson with his Mass Observer's badge And his notebooks: there were twenty thousand odd.

And he'd not been gone a week when a report arrived for Madge: Heaven's 83.4 per cent pro God.

We are also solemnly told exactly what Field-Marshal Viscount Montgomery thought and said. I would only comment that I personally would pay more attention on this issue to the views of a branch chair- man of the Young Conservatives or of the Trade Unionist Advisory Committee than to those of Lord Montgomery.

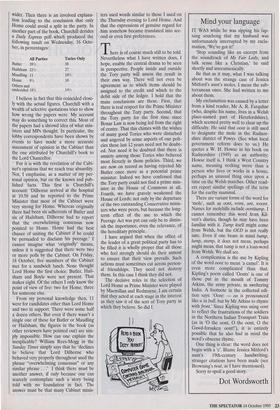

The point of view of the constituency associations at Blackpool is put forward in Churchill's book as 60 per cent for Hail- sham and 40 per cent for Butler. This doesn't seem to leave much for the rest of us and the spread was of course much wider. Then there is an involved explana- tion leading to the conclusion that only Home could avoid a split in the party. In another part of the book, Churchill derides a Daily Express poll which produced the following result on Wednesday, 16 Octo- ber, in percentages:

All Parties Tories Only

Butler 391/2

38 Hailsham 2P/2 27 Maudling 11 10I/2 Home 9'/, 10 Others and undecided 18'/2 14V2

I believe in fact that this coincided close- ly with the actual figures. Churchill with a wealth of selective quotations tries to show how wrong the papers were. My account may do something to correct this. Most of the papers had a shrewd idea of what min- isters and MPs thought. In particular, the lobby correspondents have been shown by events to have made a more accurate assessment of opinion in the Cabinet than the one attributed by Churchill's book to the Lord Chancellor.

For it is with the revelation of the Cabi- net's opinions that we reach true absurdity. Not, I emphasise, as a matter of my per- sonal opinion, but on the known and pub- lished facts. This first is Churchill's account: Dilhorne arrived at the hospital at 10.56 and he reported to the Prime Minister that most of the Cabinet were very strong for Home. Whereas originally there had been six adherents of Butler and six of Hailsham, Dilhorne had to report that the overwhelming consensus now pointed to Home. Home had the best chance of uniting the Cabinet if he could be persuaded to disclaim his peerage.' I cannot imagine what 'originally' means, unless it is suggested that there were two or more polls by the Cabinet. On Friday, 18 October, five members of the Cabinet met for a sandwich lunch. None thought Lord Home the first choice. Butler, Hail- sham and Boyle were not present. That makes eight. Of the others I only know the point of view of five: two for Home, three for someone else.

From my personal knowledge then, 11 were for candidates other than Lord Home and two in support. There were some half a dozen others. But even if there wasn't a single one of these for Butler or Maudling or Hailsham, the figures in the book (as other reviewers have pointed out) are sim- ply impossible. How can one explain the inexplicable? William Rees-Mogg in the Sunday Times simply says that he `declines to believe that Lord Dilhorne who behaved very properly throughout used the phrase "overwhelming consensus" or any similar phrase . .' I think there must be another answer, if only because one can scarcely contemplate such a story being told with no foundation in fact. The answer must be that many Cabinet minis- ters used words similar to those I used on the Thursday evening to Lord Home. And that the expressions of genuine regard for him somehow became translated into sec- ond or even first preferences.

There is of course much still to be told. Nevertheless what I have written does, I hope, enable the central drama to be seen in perspective. People inside and outside the Tory party will assess the result in their own way. There will not even be agreement as to which items should be assigned to the credit and which to the debit side of the ledger. I hold that the main conclusions are these. First, that there is real respect for the Prime Minister throughout the Tory party. Second, that the Tory party for the first time since Bonar Law is now being led from the right of centre. That this chimes with the wishes of many good Tories who were disturbed and angered by some aspects of our poli- cies these last 12 years need not be doubt- ed. Nor need it be doubted that there is anxiety among those Tories who believed most fiercely in those policies. Third, we are now on record as having rejected Mr Butler once more as a potential prime minister. Indeed we have confessed that the Tory party could not find a prime min- ister in the House of Commons at all. Fourth, we have gravely weakened the House of Lords; not only by the departure of the two outstanding Conservative minis- ters who were peers, but because the long- term effect of the use to which the Peerage Act was put can only be to dimin- ish the importance, even the relevance, of the hereditary principle.

I have argued that when the office of the leader of a great political party has to be filled it is wholly proper that all those who feel strongly should do their utmost to ensure that their view prevails. Such actions must sometimes cut across person- al friendships. They need not destroy them. In this case I think they did not.

The decisive roles in the selection of Lord Home as Prime Minister were played by Macmillan and Redmayne. I am certain that they acted at each stage in the interest as they saw it of the sort of Tory party in which they believe. So did I.

Previous page

Previous page