Last Word

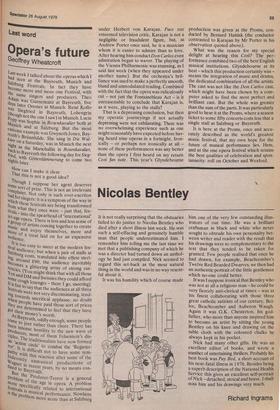

Opera's future

Geoffrey Wheatcroft

Last week I talked about the operas which I had seen at the Bayreuth, Munich and Salzburg Festivals. In fact they have become more and more one Festival, with the same singers and producers. Theo Adam was Gurnemanz at Bayreuth, five days later Orestes at Munich. Rene Kollo Was Siegfried in Bayreuth, Lohengrm (though not the one I saw) in Munich. Lucia PoPP was Sophie in Rosenkavalier both at Munich and at Salzburg. But the most extreme example was Gwyneth Jones, Bayreuth's Briinnhilde. She sang in Die Walkure on a Saturday, was in Munich the next night as the Marschallin in Rosenkavalier, back to Bayreuth the following day for Siegfried, with Gdaerdirimmerung to come two flights later.

How can I make it clear That this is not a good idea?

Though I suppose her agent deserves soMe sort of prize. This is not an irrelevant c,mtiplaint. Not only is such over-exertion oad. for singers: it is a symptom of the way in Which these festivals are being transformed 11-.°111 what they once were — just that, festivals— into the spearhead of 'international' let-age opera. There is less and less sense of gro.up of artists coming together to create In.:Isle and enjoy themselves, more and more audie of a treat laid on for an expensive It is too easy to sneer at the modern festival audience; but when a pair of stalls at `3alZbUrg costs, translated into effete sterlLing, around £90, the audience inevitably becomes a glittering array of strong currvencies. (You might think that with all those en and DM and Swissies they could afford set-ft cough lozenges — there I go, sneering). It is fair to say that the audiences at all three festivals were not very discriminating, tending towards uncritical applause: no doubt they people have paid those sort of prices "ley are determined to feel that they have got their money's worth. At Bayreuth, oddly enough, some people eLonte to jeer rather than cheer. There has been intense hostility to the new wave of Producers, most of them Felsentein's disciples. The traditionalists have now formed att 'action circle' to combat the `Regieterru r'. It is difficult not to have some symrinhy with this reaction after some of the iueously

Wa unmusical productions of li gmer in recent years, by no means conned to Bayreuth.

But the Producer-Terror is a general Problem of the age in opera. A Problem More specifically related to international festivals is musical performance. Nowhere is the problem more acute than at Salzburg

nee. under Herbert von Karajan. Pace our esteemed television critic, Karajan is not a negligible or fraudulent figure, but, as Andrew Porter once said, he is a musician whom it is easier to admire than to love. After hearing him conduct Don Carlos even admiration began to waver. The playing of the Vienna Philharmonic was stunning, as I said last week (when they appeared under another name). But the orchestra's brilliance was used to make a perfectly smooth, bland and unmodulated reading. Combined with the fact that the opera was ridiculously cut — not just the Fontainebleau Act — is it unreasonable to conclude that Karajan is, as it were, playing to the stalls?

That is a depressing conclusion, but then my operatic journeyings if not actually depressing were not exhilarating. There was no overwhelming experience such as one might reasonably have expected before having heard nine operas in a fortnight. Ironically — or perhaps not ironically at all — none of these performances was any better than the opera I first heard on my return Cosi fan rune. This year's Glyndebourne production was given at the Proms, conducted by Bernard Haitink (the conductor contrasted to Karajan by Mr Porter in his observation quoted above).

What was the reason for my special delight at hearing this Cosi? The performance combined two of the best English musical institutions. Glyndebourne at its best — which this production certainly was — means the integration of music and drama, the dedicated combination of all the artists. The cast was not like the Don Carlos cast, which might have been chosen by a computer asked to find the most perfect and brilliant cast. But the whole was greater than the sum of the parts. It was particularly good to hear it at the Proms, where a season ticket to some fifty concerts costs less that a single stall at Salzburg or Bayreuth.

It is here at the Proms, once and accurately described as the world's greatest music festival, that my own hope for the future of musical performance lies. Here, and at the one opera festival which retains the best qualities of celebration and spontanaeity: roll on October and Wexford.

Previous page

Previous page