Jordan

Succession and security

Sandy Gall

Understandably, King Hussein's divorce from Princess Muna has had a field day in the gossip columns. The marriage of Toni Gardiner, English, blonde and only nineteen to the dashing young King in 1961 was in the best romantic tradition. The opposition of the nationalists in Jordan — because Muna was foreign and still a Christian in their eyes despite her conversion to the Moslem faith — only made the romance more intriguing. This time it's not the nationalists who are upset by the rapid divorce and remarriage, but the traditionalists. They say the King has done the wrong thing. This is his third marriage and he already has five children. He is supposed to set an example, and so on.

There is very little evidence in Jordan for the sort of interpretation that the press here has been putting on the new marriage: that it is politically inspired and that Hussein wants an heir of fully Arab blood. One of his principal advisers told me the other day in Amman that political considerations, far from being a major factor, were not even a factor in the marriage. Political advisers have their commitments and he may not have been giving me a straight answer. But then, if it were true, why not say so? It would be understandable, if ungallant, for the King to say that owing to high reasons of state and in the interests of national reconciliation, he was divorcing English-born Muna and marrying Jordanian-born Alia — the same name as his eldest daughter, incidentally.

Not very flattering to Alia? But he could always have said that, in addition, he loved her. As it is, that is all he is saying: that it is a perfectly normal love match. Certainly, when I saw him the other day, he looked very happy. Of course it is natural that journalists should look for political undertones, especially in the Middle East. And on the face of it the political ramifications are fascinating. Queen Alia comes from the prominent Toukan family. Her father is an ambassador, and a distant relative, Ahmed Toukan, was Prime Minister immediately after the 1970 war with the Palestine guerrillas. The family comes originally from Nablus, on the West Bank of Jordan, in what was originally Palestine. But Alia and her father were born in the East Bank town of Salt, north of Amman. Now many distinguished Jordanian families come from the old Palestine. The Tel family, for example, came from Haifa over 100 years ago. This did not stop Wasfi Tel, three times Prime Minister of Jordan, being assassinated by Palestine guerrillas in Cairo last year.

Deciding who is and who is not a Palestinian is not all that easy. The fact that her family have many connections on the West Bank cannot do Hussein any harm. But it is doubtful if it will do him much positive good. Israeli occupation has prised the West Bank away from Hussein economically, and politically it has probably encouraged extremism, in the shape of support for the Fatah guerrillas. It will take more than a smiling young Queen to bridge that formidable gulf. And on top of all that, the King must know that the West Bank is pretty much of a lost cause anyway.

Whatever the truth behind the reports of secret meetings between Hussein — or his envoys — and the Israelis, very little seems to have come out of them (if there have been any). Seen from Amman, the outlook is as bleak as the wintry slopes of the Judean Hills, The Jordanians will tell you that there is no sign of rapprochement, no sign of the Israelis being prepared to vacate the West Bank or East Jerusalem; in fact they are not even prepared to talk about Jerusalem. And no one can do a deal on that basis, the Jordanians say. The same goes for the Egyptians. These are the hard facts of Jordanian life and beside them the question whether Hussein's bride is an East Banker, a West Banker or a Palestinian really pales into insignificance.

There is one other misunderstanding that should be disposed of: the suggestion that Hussein wants an heir of his own who can succeed him on the throne of Jordan, his two sons by Muna being ineligible. This is just not true. Under the constitution there are only two conditions for the succession. First that the heir is in the direct line. Second, that both parents are Moslems. Abdullah and Feisal fulfil both conditions, and therefore, constitutionally, Hussein would have every right to change his mind and designate one of them as his successor if he so decides. There is only one catch. The government and Parliament have to endorse his decision, and that might cause problems.

On the other hand, Hussein usually gets his way. As one adviser put it: "Hussein is Jordan, and Jordan is Hussein." He made his younger brother Hassan his heir in the first place because if he had died or been assassinated he did not wish to be succeeded by a minor. If he has a son by Queen Alia that will still be the situation.

Being a pragmatic and not a hypothetical thinker, and given the turbulent politics of the Middle East, Hussein will probably leave things as they are. But he can always change his mind.

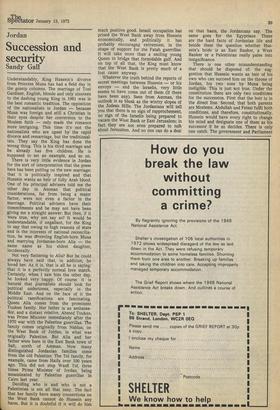

But the succession is really a red herring. Much more significant is the current swing of official thinking away from Britain and towards the United States. It is not surprising, but it has tended to be obscured by the concentra tion on palace intrigue. In its most obvious and personal form, it affects Hussein, his family and his senior officials. It's doubtful if Hussein, despite his many friends here, and his background of Harrow and Sandhurst, will visit Britain again in the foreseeable future. The reason, quite simply, is security, or lack of it.

Since the day, last summer, when Black September tried to assassinate the Jorda nian Ambassador, in broad daylight, a hundred yards from his Embassy, pumping sixty bullets into the back seat of his official car and only managing to hit him in the hand, the Jordanians have drawn their own rather bitter conclusions. The king's two sons are now in school in America, where security is said to be much tougher, and his daughter Alia is back in Jordan. All were being educated here. The Ambassador told me he would not risk coming back to London again, despite the fact that he dearly loves the place. On a more impersonal level, the Jordanians say that since our withdrawal from the Gulf, we seem to have lost interest in the Middle East, that Britain gives Jordan very little financial aid and no military aid — in the sense that they have to pay for every piece of equipment bought from us.

It is an interesting speculation that the thirty or so Centurions they recently purchased from Britain were probably paid for by Washington. Why not buy American in the first place? So when King Hussein visits President Nixon next month ,he will no doubt ask for, and receive, enough money and weapons to make his trip worthwhile, without upsetting the balance with Israel. Hussein's concern is to remain strong enough to keep order at home against any comeback by Fatah, or (with Colonel Gadaffi stoking the fires in the background) the Syrians.

Hussein knows very well that if anyone can twist the arm of the Israelis, it is President Nixon in his second and final term. He may not be able to do so. But at least it is worth being on good terms with him. Hussein is good at putting his own case, face to face.. With American money, he can also do something positive about the impecunious Jordanian economy. It was perhaps a taste of things to come that at Christmas the Jordanians invited 300 American choristers to sing Handel's Messiah before the King and his new Queen in Amman.

Previous page

Previous page