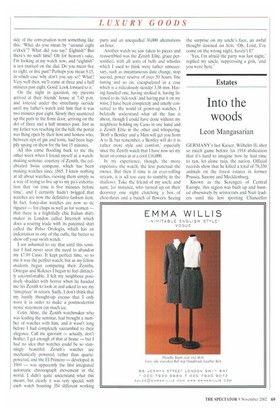

Into the woods

Leon Mangasarian

GERMANY's last Kaiser, Wilhelm II, shot so much game before his 1918 abdication that it's hard to imagine how he had time to run, let alone ruin, the nation. Official records show that he killed a total of 78,330 animals on the forest estates in former Prussia. Saxony and Mecklenburg.

Known as the Serengeti of Central Europe, this region was built up and hunted obsessively by aristocrats and Nazi leaders until the less sporting Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder moved the unified government from Bonn in 1999.

For the next two years these estates — full of red deer, moufflon sheep, fallow deer, roe deer and huge numbers of wild boar — are on sale at way below their market value. In recent years wolves have crossed over the Polish border and reestablished themselves in Saxony. and probably also in Brandenburg. Even the odd moose has turned up.

The region is as loaded with history as it is with game. Hermann Goering had a huge hunting estate north of Berlin in the Schorfheide, where he paraded about in bizarre clothes. Named after his dead wife, Carinhall hunting lodge was blown up by Goering's guards as the Red Army arrived in 1945. All that remains is the ceremonial entrance gate and spooky black-and-white photos.

The communist East German leader Erich Honecker was a passionate, if not always sporting, hunter. Gamekeepers would shoot hares in advance of state hunts, freeze them, and then discreetly add them to the ceremonial post-hunt laying out of the kill.

This is big country and — in sharp contrast to western Germany — much of it has a low human population. It is utterly unlike the packed Frankfurt, Dusseldorf, Ruhr Valley corridor, and encompasses the spruce-covered Erzgebirge Mountains along the Czech border, the Harz Mountains on the former German–German frontier, and flat expanses of pine forest in Brandenburg state, which surrounds Berlin. Towards the Baltic Sea coast in the north, the forests are a mixture of oaks, pines, spruces and beech trees bordering on fields.

There are still 300,000 hectares of woods and even more farmland to sell, but don't prevaricate — Germany's state privatisation agency, the BVVG, says that all larger forest properties will be sold by 2004. Castle and manor houses in varying states of neglect are available for next to nothing, and, although the sale of agricultural land is limited to German citizens and European Union nationals, forest sales are open to all international buyers regardless of citizenship.

The BVVG is putting up forests for sale ranging in size from 25 to 800 hectares (62 to 1,976 acres). In order to get hunting rights for a Vagdrevier", you need to buy at least 75 hectares in most states and 150 hectares in Brandenburg. The price per hectare depends on the type, age and quality of trees on the property (all properties are meant to be cropped for timber). Prices range from 500 euros to 800 euros per hectare for average forests in Brandenburg state to more than 2,000 euros per hectare in sought-after areas in Saxony and Thuringia.

If, like me, you are barely able to con

tam n your excitement, there are a few words of warning: the property being sold was seized by the communists after the Nazi defeat in 1945. Following the 1990 German unification, the former chancellor Helmut Kohl decided not to return the lands to the former owners, and only to pay a tiny, token compensation. Kohl claimed non-return was a condition set by the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev for allowing unification to go ahead, although Gorbachev later denied this in repeated interviews. In any case, what you will be buying is, in effect, stolen goods, although the sales have been sanctioned by several rulings of Germany's highest court.

The BVVG lists forest properties for sale on its Internet site (www.bvvg.de). Included is a brief description, a map showing location, types of trees and hunting status. Texts are in German. A more detailed folder on each forest can be ordered, which provides exact descriptions of the timber, soil types, more maps and the name and phone number of a local state forester who can show you the property.

Forests put up for sale remain listed for an eight-week period. After this time the property is taken off the website and bids are evaluated. The winning bid is the one which provides the best management plan for the forest over the next 20 years. But here is the catch: the successful buyer cannot sell the property for two decades.

The 20-year rule is one of the main reasons the property is sold under the market price. I paid 750 euros per hectare for the 354 hectares I bought in Brandenburg, although the current free-market price was around 2,000 euros. Bids are cost-income projections based on profits from timber offset by expenses including work needed to be done to conform with management plan, forestry laws and state forest goals. Kleinsee Forest, which I bought, consists of 88 per cent pines, and I am committed to convert ing a set number of hectares a year to oaks and a native spruce. This does not come cheap: clearing, fencing and replanting one hectare can cost 5,000 to 7,500 euros. In my case, costs are covered by annual timber sales revenue.

Also needed with the bid is an explanation of why you want to buy the forest. What's required here is a nice mixture of communing with nature, environmentally correct logging and jobs for the region. The complete management plan is generally about 25 pages long and must be submitted in German. I don't have any formal training in forestry so I turned to professional foresters, who will write up such proposals for a fee of about 1,000 euros. The same goes for running the forest once you buy it. Numerous private firms and the state forestry offices will manage the property for a fee.

Viewing the properties may be timeconsuming but it's a fine way to discover some of eastern Germany's most beautiful — and haunting — regions. I toured Biehain Forest in Saxony, near the Polish border where the Red Army stormed across the River Neisse in 1945. In the middle of the property I found a wooden cross over a sunken grave with the words 'An Unknown German Soldier'. Somebody had laid fresh flowers on the grave. Trees older than 80 years are likely to contain bomb shrapnel, the local forester warned. Because of such war legacies, sawmills in the region have metal detectors which scan logs before cutting.

Further north in Jerischke Forest the zigzag German defence lines were still evident among the pines and spruces from which the battered Wehrmacht put up its final battle with the Red Army. My German father-in-law, who as an 18-year-old fought nearby in 1945, said he and the other soldiers had been so terrified by the onslaught that they defecated in their pants. Jerischke village today is a German version of Sleepy Hollow, with wide fields sloping up to the woods lined with 250-year-old oaks. The road running through it hits the Polish border a few miles away as a dead end.

Closer to Berlin 1 discovered some of the region's least-known and most beautiful lakes, such as Oderin See. Although very attractive, I reluctantly chose not to bid for forests bordering lakes because they draw large numbers of visitors, especially at weekends.

This, indeed, is a point which should be noted. In Germany landowners are not allowed to post their property or keep out the public. Under German law, anyone has a right to hike and walk through forests and fields, ramblers don't have to stick to footpaths and are allowed to do things like collect mushrooms. Nobody would dream of asking permission. As pleasant as this may be for the public, for landowners it represents an unhappy creeping erosion of property rights

which are taken less seriously in Germany than in most Anglo-Saxon countries.

Before the final signing for the sale I spent a few sleepless nights wondering if it would not be wiser to follow my original idea, which had been to buy a woodland in New England. Oddly enough, it was a Potsdam lawyer, recommended by friends to review the contract, who told me not to wait and insisted that the current privatisation is one of the least-known and best land deals going in any stable Western country.

'It's all OK. Just sign the damn thing before anybody changes their mind,' said Christian Graf Brockdorff, who has bought forest and agricultural properties in two eastern German states. 'This is a one-time chance — I'm buying as much as I can.'

Leon Mangasarian is Berlin correspondent for the Deutsche Presse-Agentur (dpa) International Service.

Previous page

Previous page