Tax Credits

The poverty trap

Bruno Stein

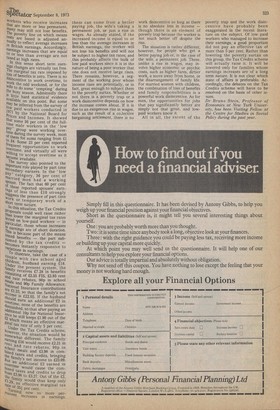

'Months of ongoing debate can be expected now that the Select Committee on Tax Credits bass submitted its report. The proposals for a tax credits scheme are aimed mainly at improving the systein for taxing incomes, and that is what the debate ought to be mainly about. But in practice much of it will also be about the limited contribution that the, proposals can make to the relief 01 poverty — and about assessments' of the nature of the so-called poverty trap, and its alleged disincentive objects. The poverty trap argument arises from the fact that, as the incomes of low-paid workers go al) benefits theoretically go down' income tax comes more into PIO and National Insurance contributions must still be paid. Calcula' tions adduced for this argument are generally made on the es; sumption that benefits respolw immediately to changes in earn' ings. An extreme case of such a calculation is the married couPle with two school-aged chilaren where the husband's earnings have gone £22 to £24. They ar parently stand to lose 34p in rent rebate and 90p in schools meals' At the same time, they have to pay an additional 70p in incoine tax and graduated insurance con' tributions. A £2 rise thus appear!. to have left the family better of' by only 6p, which is like paying a 97 per cent marginal tax rate,. Depending on one's priorities ano choice of rhetoric, this is said t° mean either that the family is trapped in poverty, since highedi earnings do not make it better er'' or that the family has no incentive to increase its work effort. Tile problem is recognised in the Green, Paper, and one of the purposes n' the Tax Credits scheme there proposed is said to be to mitigat,e the anomaly of having low NIL" workers subject to tax rates of ay, to 100 per cent. G. F. Fiegehen P. S. Lansley (National Institute Economic Review, May 1973) ha'„e indeed calculated that the Ti" Credit proposals will lower Mar: ginal tax rates in all but the lovas' income ranges. There are reasons to believe that many of the earning' increases of poor workers are in practice not caught in this waY' Many of the working poor raise their earnings by temporarli,Y increasingtheir labour supplY, forms such as overtime ant weekend work. The fact thn.,,, benefits like Family Incorli) Supplement (F1S), free sclion, meals, and rent and rate rebate,' tend to be granted for lige' periods allows these short terT changes in income to be ignorell In the circumstances, the hig„„ marginal tax rate will not CO into play. Moreover, even anion°

workers who receive increases that are more or less permanent, many may still not lose benefits. The poverty line on which means tests are based is adjusted annually to reflect average increases in British earnings. Accordingly, earnings increases that are equal to or less than average are not taxed at high rates.

In this sense short term earnings changes are virtually tax free. The marginal tax rate imposed by 1°8s of benefits is zero. There is no disincentive to work overtime, to work the odd weekend, or for the Wife to do some ' tempting ' during the busy season. Admittedly there IS little hard statistical evidence available on this point. But some 1.11, aY be inferred from the survey of 'ow paid workers conducted in 1971 by the National Board for Prices and Incomes. It showed that some 36 per cent of the fulltime male workers in the low Pay group were working overtime during the survey week, most of them for sums ranging from £1 ,1° £4. Some 23 per cent reported ,requent opportunities to work overtime, and virtually all were Willing to accept overtime as it became available. The survey also pointed to the 1mPortant role played by part time secondary earners. In the 'low Pay category, 36 per cent of Married men had a working sPouse. The fact that 60 per cent Of these reported spouses' earnings of less than £10 strongly st18gest5 the presence of part time Work or temporary work of a Short term nature.

In this situation, the Tax Credits

than could well raise rather man lower the marginal tax rates levied on low-paid workers — in ?articular, those whose increases ..r'learnings are of short duration. is because part of the means tested benefits — the part sub1-Imed by the tax credits -becomes instantly responsive to variations in earnings. To illustrate, take the case of a couple with two school aged children, husband earning £16. Under the present system, the '411111Y receives E7.28 in benefits consisting of £2.55 FIS, £2.93 rent aod rate rebates, 90p in school meals and 90p Family Allowance. National Insurance contributions are £1.23, so that the family's net I1,1corne is £22.05. If the husband Should earn an additional £2 in ,overtime, none of the benefits are ulminished, so that after paying an additional 10p for National InsurZoce he still keeps £1.90 out of the 2 which means an effective marginal tax rate of only 5 per cent. Under the Tax Credits scheme, however, the situation would be somewhat different. The family _earning £16 would receive £2.21 in rent and rate rebates, 90p in C1-11301 meals and £3.98 in combined taxes and credits, bringing `lle family's net income to £23.09. an additional £2 earned in overtime would cause the corn-,

from

taxes and credits to drop £3.98 to £3.27. Out of the £2, the emfanlily would thus keep only r an effective marginal tax of 3.51 per cent.

urning now to more perMal-lent increases in earnings, these can come from a better paying job, the wife's taking a permanent job, or just a rise in wages. As already stated, if the increased income is equal to or less than the average increases in British earnings, the worker will not lose his benefits and will not be subject to higher tax rates; and this probably affects the bulk of low paid workers since it is in the nature of being a poor worker that one does not receive large rises. There remains, however, a segment of the working poor whose income rises are potentially, or in fact, great enough to subject them to the poverty surtax. Whether or not there is a poverty trap or a work disincentive depends on how the increase comes about. If it is due to an exogenous rise in wages, such as the result of a codective bargaining settlement, there is no work disincentive so long as there is no absolute loss in income — though there is an element of poverty trap because the worker is not much better off despite the rise.

The situation is rather different, however, for people who get a better paying job or, in the case of the wife, a permanent job. These, unlike a rise in wages, may involve higher economic or psychic costs, such as higher fares, dirtier work, a move away from home, or the disarrangement of family life. For married women with children, the combination of loss of benefits and family responsibilities is a powerful work disincentive. As for men, the opportunities for jobs that pay significantly better are simply not that great, and lowpaid workers know it. All in all, the extent of the poverty trap and the work disincentive have probably been exaggerated in the recent literature on the subject. Of low paid workers who managed to increase their earnings, a good proportion did not pay an effective tax of more than 5 per cent. Rather than lowering the poverty surtax on this group, the Tax Credits scheme will actually raise it. It will be lowered only for families whose earnings increases are of a long term nature. It is not clear which state of affairs is preferable. Accordingly, the debates on the Tax Credits scheme will have to be resolved on the basis of other issues.

Dr Bruno Stein, Professor of Economics at New York University, has been Visiting Fellow at the Centre for Studies in Social Policy during the past year.

Previous page

Previous page