illichatril 1101 Prorrtbingd in Parliament.

1. ALTERATION OF THE CORN LAWS.

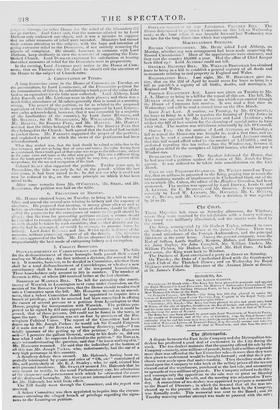

Several petitions were presented at the morning sitting of the House of Commons on Thursday, for an alteration in the Corn-laws. That which had received by far the greater number of signatures was one from Glasgow, presented by Mr. Oswald, to which no fewer than fifty-nine thousand names were appended. A number of petitions were also presented from agricultural districts, against any alteration in the present system. At the evening sitting of the House, Mr. HUME presented a petition signed by thirty-one thousand inhabitants of the Metropolis for the repeal of the Corn-laws. He also presented similar petitions from Sheffield and other places ; and, after they had been read, rose to address the House on the subject. He began by stating the great importance of the question, and the necessity of discussing it without heat or intemperance of manner. Last year, there was much personal feeling excited by the discussion ; but the Representatives of the People would best discharge their duty by taking a large view of the subject, and addressing themselves to the task of remedying the grievances of which their constituents complained. He would call attention to the parties who were interested in the decision of this question. On the one hand, was the great mass of the people ; on the other, the privileged few, who had obtained, by means of their undue influence in the Unreformed Parliament, an advantage over the rest of the community, which, at no matter what expense, they were determined to retain. He complained, on behalf of the great body of the people, of this hurtful monopoly possessed by the landed proprietary. The rights of the people had been for a long time in abeyance, but in the Reformed Parliament he trusted they would find protection. Mr. Hutne then gave in detail the history of the enactments for regulating the trade in corn, from 1660 downwards ; and pointed out their constant inefficacy to produce the result desired by those who framed them ; till the year 1815, when the commencement of the present excessively restrictive system began. The bill of 1815 had the effect of raising the price of bread in this country, but not to the extent which the landholders desired. Mr. Hume next referred to the vast increase in the population of our great manufacturing towns ; and dwelt upon the necessity of furnishing an increased supply of food for their maintenance. When so large a portion of the population were dependent upon manufactures for support—when that class of the population was so rapidly increasing—would it be possible to prevent the importation of foreign corn ? The agricultural produce of the country could not increase in any thing like the same proportion. The great disadvantage with which our manufacturers had to contend, was the low rate of wages, the consequence of the low price of food, for which labour could be had on the Continent. We had cheap cotton, and wool, and cheaper fuel, but food was dear. While the Corn-laws had failed to benefit the landed interest,the rest of the community were starved by the artificial want which they created. A reduction in the price of corn would be followed by a reduction in the price of wages. It might be asked how then would the manufacturer gain ? He would answer, that food would be proportionably cheaper; that England being the principal corn-market, would strike the average of Europe, and at the same time, by her cheaper production, secure a market against the competition of foreign manufacturers. The carrying-trade would become our own, were there a regular trade in corn established wider a fixed duty. At present, corn was imported into this country in foreign vessels ; because our shipowners, many of whom were merchants, could not calculate upon so uncertain a trade. The landed interest founded their claim for a duty on corn on the ground that land was subject in this country to peculiar burdens. There were tithes, poor-rates, county cess, local and parochial taxation, and Church-rates. But they had purchased their land subject to tithes : the impost had existed from time immemorial, and from 1700 to 1815 no claim for relief had been set up on this ground. With the regard to the others, let the Mouse look at the burdens which they laid upon towns. There were the poor-rates ; the expenses of paving, lighting, and watching ; and the Church-rates, from which the landed interest was peculiarly free. The county rates, as he could prove, pressed more heavily on the manufacturing than the agricultural counties, lie was reminded of the Malt-tax : that fell heavily upon the land, but it also fell heavily on the consumers of beer. Mr. flume then adverted to the baneful influence of our Corn-laws upon our foreign trade, and mentioned the steps now taking in Germany in retaliation of them. On the other hand, the proceedings of the people of South Carolina, and more recently of the vine-growers in the South of France, showed a determination not to submit to injurious restrictions on commerce. England should take the lead in removing these restrictions. It was most peculiarly her lute rest to do so. lie was for removing prohibitory duties also on foreign manufactures : he would get rid of the restrictive system. It was admitted by all except some ultra landed gentlemen, that the pi esent Cornlaws could not be kept up much longer. Unless trade was relieved from the pressure upon it, it would be impossible to find employment for the .millions engaged in manufactures, and bringing up to those occupations. Yet as the land was not able to mait tam n them, they must be maintained by manufactures, if at all. '1 he farmers could not be worse off than they now are : any change M ould benefit them—the few entangled in long leases only excepted. He had formerly advocated a duty of 15s. a quarter, to be reduced by one shilling a year, till it came to the point at which the agriculturists had a claim to protection in consequence of any exclusive taxation beyond what other classes were liable to. He now, however, thought that 10s. should be the point at which they should begin to reduce. Mr. Hume concluded by moving, " That this House do resolve itself into a Ccmmittee, to consider of the Corn-laws, and of substituting, instead of the resent graduated scale of duties, a fixed and moderate duty 011, the import at all times of foreign corn into the United Kingdom, and for granting a fixed and equivalent bounty on the export of corn from the United Kingdom.

Colonel TORRENS seconded the motion. He thought it was necessary to the peace and prosperity of the country to abolish every restriction on the importation of food. The agriculturists had only one argument for the support of their views : it was this—that in a country like England, so densely inhabited by a manufacturing population, it was dangerous to trust to foreign countries for a regular supply of corn and food. That was not a valid argument. Besides they argued inconsistently with their own principles : if they wished the people to be independent of foreign corn, why restrict the importation of barley ? Why object to the use of sugar and molasses instead of malt ? If barley were admitted duty free, the land now devoted to the growth of barley might be employed on the growth of corn, and thus a larger quantity of human food be produced. It was said that the home market was best for the manufacturer ; so it was for the agriculturist. There never was a rich agricultural country which had not large manufacturing towns for the sale of its produce. He warned the House of the danger of driving manufactures out of the kingdom, and enlarged upon the advantages which in a variety of ways the landlord would obtain from such a great increase of manufactures as the repeal of the Corn-laws would produce. The prosperity of the landed interest was based on that of the commercial and manufacturing interests, fie asked the supporters of the Corn-laws, whether it was likely that the great manufacturing communities would long submit to their monopoly ? Would the great towns allow the landholders to depress the wages of their population for the selfish purpose of augmenting their own rents? The intelligent and important towns who owed their greatness to manufactories, would not allow the landholders so to act. He trusted that the Irish Members would all vote for the motion. They would if they acted consistently. If corn were drawn from Poland, more would be left for Ireland : at present, the absentees drew the produce of Irish labour out of the country. The cause of Irish distress was high rents ; and nothing would tend to reduce rents in Ireland so much, as allowing England to get corn from foreign nations. Colonel Torrens expatiated on the great advantages which the possession of fuel gave this country over rival nations. Her mines of coal were far more valuable than mines of silver and gold. All we wanted was the cheap corn which the foreigner had. It was said that if the Corn-laws were abrogated the price would not fall in England. He cared not about that. If it did not fall here, it would rise on the Continent, and thus the comparative advantages which the foreigner possessed at present would be at an end.

Sir JAMES GRAHAM took the lead in opposing the motion. He would, he said, undertake to prove that the maintenance of the Conilaws was for the interest of the nation. He agreed with Mr. Hume, that the question was to be looked at as it regarded the interests of all classes. It was also very desirable that it should be settled. But Mr. Hume said it could only be settled in one way--by repealing the Corn-laws—by conceding every thing he asked for. Now, to give up the Corn-laws, was inconsistent with the preservation of a landed aristocracy. If that were of no importance, it would also destroy the farmers, and put an end to the occupation of the great body of agricultural labourers. Mr. Hume had thought proper to extend his views of the question, and refusing to limit it to a question of British policy, thought proper to consider it as one of European policy. Now be was content merely to treat it as a British question alone. Sir James then read an extract from the writings of Mr. Huskisson, the Coryphieus of free trade, in favour of the Corn-laws. The passages were written in 1815; and he asked if Mr. Huskisson had changed his opinion ?

Mr. HUME said, "Yes."

Then, Sir JAMES GRAHAM continued, he would refer to Mr. Huskisson's opinion delivered in the Agricultural Committee of 1821, by

which it appeared that his opinions were by no means altered. Mr. Huskisson always adhered to the opinion that there was much danger in depending for a supply of corn on foreign, perhaps hostile, nations. Sir James reminded the House of the great increase of exports since 1828, when the present Corn-laws were passed. He quoted the opinion of Mr. Ricardo in favour of allowing a duty on foreign corn sufficient to coun tervail the burden of tithes. The peculiar burdens affecting corn grow ing lands amounted to one third of the rent. This was stated in a protest upon the journals of the other House ; and was undoubtedly a correct though a startling assertion. Then a fixed duty was proposed as the means of allaying popular discontent : how far it was likely to have that effect, might be judged of by an extract from a leading and in

fluential journal ; and Sir James read an extract from the Times, in

which a fixed duty on corn was denounced in strong language, as a fixed evil, a fixed robbery, &e. The effect of a free trade was to produce a fluctuation • and the prices of corn from 1673 to 1791, a period during which the trade was sometimes free and sometimes fettered, proved this. The Irish Members had been appealed to for their support of this motion : he also appealed to them. Nothing could contribute more to the prosperity of Ireland than the benefit it derived from our great consumption. He wised that benefit to be increased; and I would always prefer extending it to Ireland and our own Colonies, : rather than to the European Continent. Let the state of Poland be regarded : it was a corn-growing country, yet half its land was laying

waste, for the want of such a market as England was to Ireland. He maintained that the present system was found to work well ; that the average prices of corn had not varied much during the last century. le 1792, 50s. was the average ; now it was 48s. hid. Steadiness of price as he had stated in the Agricultural Report of the Committee of' last session, was the great thing to be sought for. This Was the labourers', the tenants', not merely the landlords' question. Mr. Oliver, one of the witnesses, had told the Agricultural Committee that it was the landlords' question ; but he afterwards explained this away ; and ad.. nutted that it was a question with which the tenant and labourer had

much to do. He stated that 900,000 or 1,000,000 of individuals might. be thrown out of employ by the importation of 3,000,000 quarters of corn. It was said that these persons might find employment in manu factures ; but Sir James appealed to Mr. Cobbett to say, whether the hard and horny hand of the labourer could be fitted for the handling of silks and muslin. He admitted that he had been mistaken in supposing that the condition of the labourer would have been injured by the alteration in the standard of value ; and he referred to the comparative amount

of coopers' wages at different times in proof of his assertion that the condition of artisans was now better than formerly. Would to God he had been also wrong in his prediction that the condition of the landed interest would also be deteriorated ; but while the landowner was obliged to reduce his rents, the weight of all his previous engagements was increased by the alteration of the standard of value. Ile concluded by declaring his firm belief; that if the present motion were carried, two thirds of the land would be brought into the market. Were this motion passed, that which would be gradual would become sudden ; that which was safe would become hazardous ; it would lead to an agrarian

law ; it would not merely a class, not only impoverish a community, it would ruin the state itself.

Mr. FERGUS O'CONNOR said that the Irish Members were unanimous in opposing the motion. Mr. RICHARDS, Mr. HEATIICOTE, and Mr. LEECH also opposed the motion.

It was supported, with great vigour, by Lord Monerril, Mr. CLAY, and Mr. CHARI.ES BULLER. Lord Moaessal said, that no better means of cheating a nation could be devised, than the present restrictive laws ; for cheated a nation must always be, which was compelled to resort to a dear instead of a cheap shop. The worst injury that could befall the agriculturists was constant uncertainty and alteration. Now the Corn-laws would not be suffered to remain unassailed ; and he was satisfied there would be no rest or safety to the agricultural population until the question was settled upon a basis just to all classes. Mr. CLAY said, in reference to the opinions of Mr. Huskisson, that when he was reproached w ith not extending the principles of free trade to corn, he always admitted the cogency of the argument, and said that it was the legislature, not he, that was averse to the principle being carried out to its fair consequences.

At the end of Mr. Boiler's speech, the debate was adjourned, on the motion of Mr. EWART.

Last night the debate was resumed. Mr. EWART, Mr. POU1ETT THOMSON, Mr. W. WHITMORE, Lord Howwx, and Mr. BROTHERTON, spoke in favour of the motion ; and the Earl of DARLINGTON, Mr. BARING, Mr. HANDLEY, Mr. C. FERGCSSON, Sir GEORGE PHiturs, Lord ALTHORP, and Lord PALMERSTON against it.

Mr. EWART dwelt upon the injury of the Corn-laws to foreign commerce; and upon the undue preponderance of the landed aristocracy, who were pampered at the expense of a pauperized and uneducated people.

The Earl of DARLINGTON professed to have paid very great attention to the subject ; and expressed his conviction of the impossibility of the British farmer raising corn to compete in price with the foreigner, if deprived of the protection of the Corn-laws. Rents, he said, had been much reduced ; but if a man were required to reduce below a certain point, he might as well be compelled to give up all his property. He would not move an amendment of which he had given notice, because he had been requested by a member of the Government to abstain from doing so, in order that the opponents of Mr. Hume's motion might not be divided, and as great.a majority as possible might be induced to vote against it.

Mr. PouLErr THOMSON made the principal speech of the evening. He began by denying the correctness of Lord Darlington's statement of the interference of Ministers on this subject. The question was an open one, as was proved by the fact that he, a member of the Government, though not of the Cabinet, was prepared to speak and vote in favour of Mr. Hume's motion.

Lord DARLINGTON said that the intimation be had received was from the highest quarter—from a member of the Cabinet.

Mr. THOMSON resumed ; and addressed himself principally to the task of replying to Sir James Graham's speech, which he characterized as a good landlord's speech, calculated to catch as many votes as possible. But he was of opinion that the repeal of the Corn-laws would place the landlords in an improved position. The House had been told that land forty years ago let for 20s. an acre, and the charges were so and so ; now the land let for the same, but the charges were 6s. more, and the rents were badly instead of well paid. But it should be

recollected, that in the prosperous times there was no actual restriction

on the trade in corn, the law for that purpose being inoperative. The farmer had been the great sufferer by the Corn-laws : he had been de

luded by them : in 1815, be was told that the law would raise the price of corn to 80s.; and numbers were induced to embark their capital in land upon the faith of that representation. Then came the Corn laws of 1827 and 1828, under which they were now suffering. Mr. Can

ning then said to the farmers, "Instead of a fluctuating price, you shall have one that shall only range between 55s. and Ws." Well, on the

25th of Jauuary 1831, the price was 75s. 11d, a quarter; and at the mo

ment he was addressing the House it was only 48s. and a fraction. Had not the farmer then been deluded? Was he not deeply injured by the

operation of these laws ? Much had been made of the evidence of Mr. Oliver before the agricultural Committee : that gentleman had said that a million of individuals would be thrown out of employ by such an alteration in the Corn-laws as would throw two million of acres out

of cultivation. But what reason vas there to expect any such result from an alteration, when prices bad fallen during the last fifteen years from Iris. to 20s. a quarter, and yet no such effect as Mr. Oliver had anticipated had followed. Mr. Thomson then referred to the Agricultural Report, to prove that the condition of the farmers and of the landed interest generally was very bad. The yeoman was suffering ; the farmer was nttelly mined. This was the effect of their boasted system of protection. He described the situation of the country at the close of the last war ; when almost all the machinery, all the manufacturing skill of the world, was centered in Eegland. We were fifty years in advance of other countries. Then was the time for entering upon an unbounded field of commercial enterprise ; and then we passed the Corn-laws, which absolutely forted other nations to manufacture for themselves. He showed, by reference to the declared value of our exports, that they were less by upwards of nine millions, in the live rats ending in lb:33, than in the five years ending in rS2'2, when there Jd1,1 bitell some importation of corn. As to the arguments about Foreigo Governments not being willing to enter into a reciprocity ilston with us, he cared little about the dispositions of governments, if we could once make it the interest of their subjects to become our customers. ?Jr. Thomson then quoted passages from Mr. Huskisson's speeches, to prove that his real opinions were in favour of a free trade in corn ; and read several long passages from a prunphlet by " a Cum. berhied Landowner," as an answer to Sir James Graham's present opinionaill favour of the Corn-laws. [ Sir James afterwards explaieed, that he was not the writer of that pamphlet, though he assisted in its publivation.] lie considered that the landowner had completely the advantage over the First Lord of the Admiralty. He then adverted to the great benefit which would result to the shipping interest from the evening of the Corn-trade ; and quoted the evidence given before the !ommercial and Manufacturing Committee in support of his opiTlitiliti. If the landlords had an equitable claim to relief, he should be willing to accede . to it. Let them make out their bill of costs, and tes would help to discharge it. He maintained that now was the best time to change. If they waited till a bad harvest here or in France raised the price of bread, they might have to deal with the Corn-laws in a less respectful manner. He concluded by quoting the words of Lord Milton—" In spite of your decisions, the restrictions on the food of the people cannot be endured."

Mr. BARING reminded the House, that the distress of the agricultural interests was particularly alluded to in the King's Speech, and that Lord Althorp had declared that the Government would oppose any attempt to nher the Corn-laws. It was to this declaration that he owed his majority on the question for repealing the Malt-tax. But now it was said that one half of time 'Members connected with the Administration would vote for the motion ! Ile proceeded to argue that the present system worked well. He said the respectable classes in the city of London by no means joined in the cry against it : the articks in the journals on that subject were, he was credibly i.1,6,nned, jibrn the pens Vforeigners, who had large quantities of corn in the London graearies. He hoped that when the usuid species of political ineendial ism was attempted to be got up the cry of "cheap bread " would not again be used: for in this debate it had been :ululated, that not " clue 'I' bread," but the establishment of what was called "sound principles " was the object aimed at. It was the extension of our foreign commerce which Mr. Thomson, it appeared, expected to flow from the repeal of the Corn-laws. Ile and those with whom he acted had been taunted with not being philusepLers, by those statesmen who would legislate for an old country like this, surrounded by the old countries of Europe, as if it were the Swan River Colony. The Governments of the continent were opposed to free-trade systems ; and no sacrifices would propitiate them. " They \-ill receive you," Mr. Ifariag continued, "with great attention. Your great philosopher, Dr. Lowring, will be puffed from one end of the Continent to the other, ia their newspapers, as the greatest genius that ever came amomg them. But there they will stop." Did not Mr. Thomson and Mr. flume in themselves to the illustrious Doctor—a werthy trio—bad they aut proceeded through France and Germany ‘vithout being able to abtaia a: •y concession from the C,vernments of those countries ? Mr. Baring witerated his assertion thtJ the present system worked well. Cownolve and manufactures flourishuui. ThiTe were a million of quert:.rs of grain in bond, ready in rase of want. It was idle to argue on thetnici. with such fiwts before their eyes. He described the rein v. Nell would fall on the (ruler by the depreciation of his stout:, should the Corn-duties he repealed ; and the helpless state of the agricultural labourers, who were scattered through hill rad dale, in case of their being thrown out of their regular emsp!oyment. If the House were to go into this mad project about food, or adopt the wild vagaries spring out of the brains of theorists, they would soon feel the consequence. If this dangerous experiment were to be tried, he hoped it would be done at once, and not by degrees. To screw down the duty year by year, from 10s, to nothing., would resemble the operation of a surg, on screwing pain out of his patient, all the time he was practising agrecably to the progressive system. The count•:y was recovering from the agony of the return to cash 'etymons. He hoped that the House would not listen to this species of protracted torture recommended by Mr. Thomson.

Lord AI:1110RP said be should vote against the motion, because there was no pressing exigency for altering the Corn-laws ; which, however, in principle, he disapproved of. Agriculture was in a greatly distressed coralitioa. The effect of adopting Mr. Hume'spotion would be greatly o aggravate that distress, and would alarm farmers and landed gentlemen. All the Cabinet Ministers would vote against the motion, though there were some Members connected with Government whom they could not control. lie could not answer those with whom he theoretically agreed on the subject of the Corn-laws; and of course luc cot:hi not answer those with whom he was to vote.

Lord l'ArmritsroN opposed the motion, on the same grounds as Lord A lthorp.

llowira supported it, because be conceived the Corn-law to be

feinted on unsound principles. The agriculturists were distressed, simply because of the protection. which hung like a millstone rouud ttwir necks, and they would not disci:cumber themselves of it. Mr. HOME replied ; and the House divided : for the motion, 135; against it, 312 ; Landlords' majority, 137. There was loud cheering by the majority on the announcement of these numbers.

2. ARMY ESTIMATES.

The House of Commons on Monday resolved itself into a Committee of Supply ; and the greater part of the evening was occupied in discussing the Army Estimates. The first motion was, that a sum of 3,036,873/. be granted to defray the charges of the land forces at home and abroad, except those employed in the East Indies. Mr. COBBETT made a rather amusing speech on this motion; though he would net move to reduce the vote, as a contract had been made for the present year, which in fairness to the soldiers should be fulfilled. But he thought the pay of the soldier as compared with that of the agricultural labourer, too high. The pay of the soldier might be estimated at Is. fid. a day.

" But it is said, that the pay which the soldier receives is not too much, con. &Hering the hardships and fatigues he is obliged to endure : he is continually changing his quarters—at one tinte broiling under a burning sun, and at another Dusts bitten by cold. The Secretary at War is a very wise, sincere, able and honest man, no doubt; but lie knows nothing about what he has betll talking of—not so much as the youngest of his children, wile is now probably in the cradle. (Much laughter.) I do know something or this tuatter front expetieuee. I have not been nude. a broiling sun, it is true ; but I have been to at least as cold a region as any to which British troops are sent, and have remained there for seven years tu,gether. I happen to know the sort of life we led there; and if ever there was a pleasant liM, ours was one. ; Our summers were 'missed in fishing. shoutinor wild pigeons, rambling about the woods, anal visiting the dwellings of the Yankee gi'rls. (Laughter.) In winter, our time was spent iu skating on the river. walking about in suow-shot•s, or sitting before an excellent fire, singing.

laughing, and drinking runt at 7d. per quart. (Laughter.) we had seven is do of flour ill the week, Maar pounds of the best meat, six ounces of butter, a quartern of peas, aud a quarter:a of rice—a greater allowance than falls to the lot of any two labourers in England." Ile thought, after this statement, that the House would not be or opiniou that the condition of the British troops abroad was very arduous.

Sir HENRY HAM/INGE said, that the convicts were better fed in England than the soldiers. The former had white bread, and, as appeared from the Report of the Poor. Law Commissioners, held it up before the soldiers, who had only brown breath, in derision, asking them, how they liked their " Brown Tommy ?" It appeared also from a scale of the somparative comfort enjoyed by different classes of his Majesty's subjects, given in the Report of the Commissioners, that the soldier was the worst off alauust of all. The lowest in the scale was the independent agrieul. mural labourer; just above hint IF as the subtler ; then came the able-bodied plumper ; next tie suspected thief, then the convicted thief; and the highest in the scale—he alio enjoyed the greatest degree of comfort—was the transported felon. Ile was ready to ailndt that the state of despondency iuto which °convict was likely to fall, rendered it nicessary. pethap. to give him a greater wittily of food than was supplied to theother persons in the scale ; hut the point lw was contending to establish was, that. in reality, the soldier was a orse oil' than a person guilty of crime and septet:m.4i° transportation. Ile therefore trusted that no reduction would be tolerated in the soldier's pay. The fact %laO, that in tiflie of war, when the soldier was pot to hard work, his rations were insnflicienband it was found necessary to increase them.

Mr. Comoser said, the Poor-law Report was full of blunders. It was not to be expected that two bishops, three barristers, and two newspaper reporters, of whom the Commission consisted, could have a practical knowledge of the question.

Mr. GUEST moved a reduction of 68,7891., to be effected by placing the Life Guards on the same footing as Infantry of the Line. Mr. Dime opposed the motion ; and went into some calculations to show that the Life Guards cost less than an equal number of the Line, making an allowance for their additional penny per day to defray the extra expence of living in.London. Mr. T. Arrw000 deprecated Mr. Guest's low, paltry economy, which would screw a pitiful saving out of the small earnings of the unfortunate soldier. These pitiful, candle-end, cheese-paring savings, were inconsistent with the national honour, and the efficiency of the public service. Mr. Attwood then alluded to the Poor-law Report.

lie had been informed by a respectable Magistrate, who was well acquainted with the county of Kent, that if an attempt were made to carry the recommendations of the Commissioners into effect within that county, it would require forty thousand men to keep Kent quiet. Ile was himself sufficiently acqultrited with Birmingham to know. that if those recommendations should ever be converted into laws, twenty thousand men would not suffice to maintain tranquillity and order itt Birmingham. Ile would lell the House what was the sitttatiou of the poorer classes of the people at Birmingham. ("Question !" from the Ministerial benches.) He held at that moment in his hand a paper a Welt he had received on the 14th of Deember from one of the overseers of Birmingham. (" Vh. oh! ") That paper contained an account of the number of vier who were engaged in that parish in heaving sand rind stones. In that parish there were sixty-cue able-Ix:died paupers heaving sand. (Loud laughter from the Ministerial benches.) They were divided into four classes. (Laughter continued from the same quar(er.) It was not a laughing matter to Muir that so many of our fellow-subjects well engaged in so painful and degrading a species of labour.

These sand-heavers had to wheel a barrow of sand, weighing a hundredweight and three quarters, up a steep hill, and then to wheel it back empty again, sixteen times a day; which he calculated was equal to it march of thirty miles a day; and single men received only a shilling a day for doing all this work.

Mr. Hume made some severe remarks on Mr. Attwood's extraordinary and almost incomprehensible speech. He alluded to his opinions on the Currency question— lie that the measure which Mr. Attwood recommended as the panacea for all the distresses of the euttutry, was the most monstious proposition that had ever been brought forward by a Representative of the People; arid he was sure that whatever the honour:dd.: Mendwr might think upon the subject, his suffering constituents at. Birmingham would not thank him for objecting to reductions which were calculated to mitigate the pressure of that taxation under which they were unfortunately groaning. Ile had scarcely ever heard a speech more full of inconsistencies. They appeared at toast inconsisteueies to him. but that might be because he was not able to understand Mr. A ttiviaxl's speech or the object at %illicit he was driving. Mr. Hume then adverted to the items of which the sum proposed to be granted was made up, and which he thought might be reduced ; but would not offer any direct opposition to the vote. After some remarks in reply from Mr. ELI.ICE and Colonel Wool), the vote was agreed to.

The next motion was for 122,I43/. for the payment of the General Staff 0 ilicers, Oflieers of the Hospitals, and the Garrisons of the Cinque l'orts, Tower of London, and Windsor Castle.

A long, but very dry discussion, took place on this motion. Mr. Et.t.e.li stated that he had not complied with the suggestions of Lord Ebrington's Committee of last session, regarding the reduction of the Staff, or the consolidation of the offices of the Quartermaster and Adjutant-Generals, in consequence of a communication from Lord Bill (upon whom lie had urged the necessity of complying with the wish of time house of Commons), in which he gave sufficient reasons for keeping the Staff on its present footing, and retaining both the Quarter

• muster and AdjutantGeneral. Mr. Ellice assured the House, that ho would not spend a shilling which could be saved; and begged Mr. Hume's forbearance on these points. With respect to the Governorship of Illindsor Castle, he also entreated Mr. Hume's forbearance. The office was in fact au appanage of royalty, and necessary to its due state and dignity. However, he could not regard it as a military office, and therefore would put it under another head, and would reduce the vote to 121,84A Mr. liustE said, he was not surprised at the resistance of Lord Hill to economical reforms in the Army. He never knew an attempt to cut down the expenditure of any public department, but the head of it found innumerable reasons for maintaining it as it stood. After some remarks on the unnecessary expense of the establishment of the Horse Guards, he moved to reduce the vote for the General Staff from 27,420/. to 18,550/. as recommended before the Committee on Naval and Alilitary Expenditure by Sir Henry Parnell. This amendment was %posed by Mr. Ewer, Sir H. Hanmeec. and Lord Eintworoa, and supported by Sir HENRY PARNELL. It was rejected, on a division, by 2-13sto 59.

Two motions were then made by Mr. O'CoNNta.r. and _Nita Guesr, to adjourn ; but were negatived, by 234 to 25, and 199 to 17. Subsequently, 90,313/. was voted for the expense of the Paymaster's and other offices ; in opposition to a motion by Mr. Hume, to reduce that Stint to 81,248/. the cost of the Pay. office ; ivhieh 1w maintained was actually an impediment and no advantage to tl:e public service. Lord -Ions Russni.t. opposed the amendment, but expressed his hope; that in the next session the promised measure for the consolidation of the Civil departments of the Army would be ready. Thu sem of 6,9771. was granted, after some opposition, for the Royal Military Asylum, and the Committee then broke up.

3. IMPRESSMENT OF SEAMEN.

This subject was brought under discussion in the Howe of ComMena on Tuesday, by Mr. BretaxonAst, who moved for a Select Cominirtee to take into consideration the practicability of devising some plan by which a regular and voluntary supply of seamen may be procured for his Alajesty's Naey, without recourse to the practice of forcible impressment." Mr. Buckingham made a long and able speech in support of his motion. He enlarged upon the cruelty of the praytiee—on its illegality—its inefliciency,—and on the violent mei.ns of resistance to pressgangs, which were justified by the verdicts of juries. Ile maintained that it was an extremely expensive mode of manning the Nevy. One of its worst con:equences was the immense number of desertions which it occasioned. Every pressed sailor cost the country twenty pounds; and there were 10,000 desertions tiurive the last war. The sailors escaped by thousands to foreign shores, end maimed the fleets of our enemies. The American Commodore Decatur had told him, that America scarcely possessed a single seeutem who had not served in British vessels, and been driven away by the fear of impres,'tient. The British merchant Vessuls were left to be neamed by foreigners ; and now it was no uncommon thing for fore4unes of eight or ten different nations to be on board of the same ship. The seamen had not petitioned for the abolition of impressment in any gnat numbers, becluse, from the nature of their calling, they cueld nor, like holdsmen, meet and consult together. There could not be a public meeting on board ship ; and when on land, it was well known what thoughtless creatures sailors were. They did not the less need protection ; which the House of Commons should extend to them. He would not deny the expediency of impressment on certain occasions. Circumstances did occas:onally arise which xvarranted the suspension of certain laws— the Habeas Corpus, for example. But such cases were only exceptions to the general rule. lie wished to give the sailor the same protection, to put him on the same footing as other Englishmen. Now, in time of peace, was the fitting opportunity for devising some measure by which this could be effected. The sailor should be made to feel an interest in the service. His time of service should be limited ; a bounty should be given him ; a good system of registration should be established. It Lyn() means followed, that because bad systems had failed, a good one could not be framed.

The motion was seconded by Mr. G. F. YOUNG. It was opposed by Sir JAMES GRAHAM ; who admitted the great importance of the question, and that its early decision was most desirable. Ile zeeerted the absolute necessity of the power of impressment being sometimes exercised. It was a necessary evil. Its legality could nut be questioned. It was an undoubted part of the King's prerogative which had been recognized by repeated decisions of the Courts and by acts of Parliament. Still it was, he admitted, highly desirable that recourse should never be had to impressment except in cases of emergency, and that it was the duty of those at the head of the Naval Administration of the country to do all in their power to find a supply of men for the fleet, without having recourse to it. With this view, he had prepared a measure which would effect in reality much more towards accomplishing Mr. Buckingham's object, than a reference of the subject to a Committee of Inquiry, according to that gentleman's proposal. Sir James then stated that he intended, that the merchant seamen should be registered, and that a certain number for the Navy should be chosen by ballot. Their prize-money would be iocreased, at the expense of the shares of Captains and Admirals, from Si. to 151. each in every 10,000/. As he had before mentioned, a thousand lads had been taken into the Navy in order to be brought up as sailors. The King's ships would no longer be converted into prisons. Facilities would be afforded to parochial authorities for apprenticing boys in the service. He would also, with a view of improving the condition of the merchant seamen, provide them means of recovering arrears of wages from their masters with increased facility. He complimented Mr. Buckingham on the calm and discreet tone in which he had brought forward his motion,—very different from that which he had adopted when speaking at some public meetings during the recess : his present demeanour atoned for his former indiscretion. Sir James concluded by moving, as an amendment, for "leave to bring in a bill to consolidate and amend the laws relating to merchant seamen, and for keeping up a register of all the men engaged in that service."

This amendment WM opposed by Mr. ROBINSON, Sir EDWARD CODRINGTON, who spoke very earnestly on the question, and by Mr. HUME. It was defended by Captain Etaaorr ; who was decidedly in favour of flogging and impressment, and denied their injurious consequences. He

gave several statements in proof of his assertion that impressed sailors were not so disposed to desert from the service as volunteers. It was utterly untrue that flogging or impressment were subjects of complaint in the Navy. The sailors preferred dogging to any other mode of punishment.

Several Members,—among whom were Colonel TORRENS, Mr. WARRE, Adibiral Farettare, Mr. LYALI, and Lord A LTIIORP,-thought that the amendment of Sir JANIF:SGRAIL 31 should be adopted; and that until his plan for supplying seamen had been tried, it would be indiscreet to abolish the practice of impressment. Air. lleestNellAta, in reply, said, that if impressment were not abolished, he was certain that the sailors would consider the registration plan a mere trick to catch them mole securely, and that not a hundred seamen would be registered. l'he House then divided : for the Committee, 130; against it, 218; Ministerial majority, 8,8. • Ilreeisettases appears to IlitTe been the best speech tleliverial ia this debate. Some passages are worth extracting. He compared art impressed sailor to a slave Th • foar vrineipal eharaeteristics of slavery were—that the individual made a -lave was torn hy haw from his family and home; Rut t la was kept in a servitude which Ise 1.atheil and abhorred; tluit lie was coerc..d in that servitude by the lash, cr the fear of the lash ; mai that if he deserted In ran away, lie was liable to be pat to death, or to la• visited hy seeli other punishment as should seem goial to his ma ;lei,. Now, if tl:e chara,teristies of slavery, so were they also of improssment : for the sailor. I, hen inliwessisl. w Is a., tone!' torn away bv hum from his family and home as the Negro m as ; he ‘i as kept in a service %%Idyll lie detested as nitwit as the News) detested the sea,. ii.' or the White; he was as much coeres.i by the dish in that s-rt ice as was the sla•ii in any of our plantations; and iii the (weld • if his deserthet, he was as lial de to be shot or filing for it as any slave in thc West Indies. If this wile titic —and be the ii dile lord opposite to deny it if lie could—where it am iiiiht y ulifferellCe het wveu slavery in our Colonies a WI coerced labour on board .rir ships There was one difference, indeed, which made impresstin•nt the more galling cowl it ion of the two ; to one mho wi:s aecustomed to consider himself as a (radium Engsli-Itman, the tru•at went he received when impressed, so different hoot that exp..rietwed by the rest of his fellow-subjects. must be infinitely mone painful than a servile I ill* was 10 the Negro, whe underwent a less change in his destiny from being to it from his early years by the slavery and suffering which In saw around British juries considered resistance to a press-gang justifiable. One ease of this kind occurred at Hull. A whaler coming from the North i a was on the point Of entering the Humber, when she was descried by one or Ili, stoe:ty's Jo. Ain.ra. whiet, immediately gave chase to her. 'f he en •w or the ivietter. heti ki..ta :fig the °Neel for Witieh the Aunora was chasing their vessel, :ind beim; iiittion,(1 to madness at the paispad of being severed, it might lie for years, loan their tamales. whom they wer, cii the point of rejoining ail .T a written; voyage, uh•termilled to shad on their own defAice. n keep the captain of their vessel harnile.ei, they cotithw.1 him in his 11, II rabbi. awl arming tliemselves with the harpoons aud lances witieli t hey had ti ,d in the w hale ikluery, llwy made a stout resktance against their invaders, :Ind al,soltite!y killed t wo nom liefore they were mastered. For this altalce they were indicted and tried at York As,izes.IhliliglI the Judge appealed to the loyalty or titCrawl Jury, and the coin ii for the proseention to that of the Petty duty, a verdict of v rceonletl S r the prisoners ; a senlict •.vhielt gave great satisfietkri to the of y,,rk getwrally, awl was followed by a general rejoicing at It all,virL l•t,tu•,1 three or .ar days.

Impressment would not answer the purpose for which it was desrgw4.. Suppoa• a war to break Lint saildenly. a c •;:tain iiittiibvr iii ,hirs would bc i. iii:si_,ul,itat POI IS/11(111th Mot PiV11101101.111111e.16 Cal/tail! 1VOIlld tiatarall! to gel his complement (if men tilled up 14 Se011 as posdble. T1,, boats would iteconlit:gly be onlered to he manned. alld at evening would be sent on shore; tor t be proi.ealig, be it obiervisl, never went to work lei day •tight, on accoatit of the fii hi hi-hi daylight afforded to eseape. Supposing tlmt Dt,000 seamen Were ill aIl r( 1 KM (4 them won't prol ably it caught by the press7ang on the first night, by sweep. log wit the tav•rns, the broth...Is, awl (heather places to which sailors gcner illy re,orted. But 19,1100 %%mild esear ; and wonhleither go into the country, or disgtibe by thioa lug tiii' their Arm hats nut' black ribands, and arraying themselves a. eari•rs, Cm:ens, 111,111111ei, Sc,.. Those ii ho coiihit flt eSe:11)0, IV011iti be probvted and sheltered ny ocs kliabitants of the town where the press took place; ter titer.: never

• et was an instance in a !tuella sailor claiming protect i4,1l from the a' tack of it pressgang iMtiol a Ilthish door shut against him, or opened to his pursuers.

Sir EDWARD CODItINGTON, in the course of a very manly speech, gave instances of the hardship occasioned by impressment to good seamen.

A man who luel been originally pressed served with hint for eight or nine years : he discharged his duty dining that time in the most reputable manner possible; awl at ilki expiration of that period, frain motives that would do honour to linuttail nat,irenamely, from a desire to sapport an aged tither and mother—lie applied for his an• charge, and offered eighty g.iiiteas to obtain it. It was refused hie,

It was a matter for just complaint that sailors, in proportion to the merits of the service, were not as yell paid and rewarded as soldiers. Ii is conviction was, that if the men were not, in consequence of the existence of impressment, treated with a certain degree of harshness on board men-of-war, they would much rather enter the Navy than the merchant service.

At the battle of Trafalgar, the primest seaman which, lie had on board his ship was an impressed American. Ile haul been taken out of an American ship, I/II the pretenee that he was a British subject, brought to England, and thence transmitted to him amongst other impressed seamen. On account of his admirable conduct in the battle, he made him a warrantAuflicer. Ile afterwards told him, 1 hat he Would be glad to remain in the English service, but that he hail a wife and family in America. VIvon he Itart not seen for many years. This seaman, like many others, had been kept in ships stathawd abroad, in order to prevent theta, having been originally impressed, from getting their discharge. That was but an instance of the odium which the maintenance iif this system gut us into with foreigners.

A class of men known by the name of "civil persons" were forced on bo.trd the King's ships.

Fn.+ persons were, in other words, the rogues and vagabonds of the country; Apri %oak hey were utterly useless as effective men, they (lid much to contaminate the rest of th, crew. Ile recollected having twenty-seven such men forced on him. Ile went to the Admiralty to remonstrate on the subject ; but he was the:•i told that he must ti u. them to make up his ship's complement. Ile was not ashamed to own it, that in proceeding to sea, he took the first opportunit y that offered to man the boats with these tellows, and let them run away, thus getting rid of a parcel of vagabonds.

Captain ELLIOTT stated, in justification of impressment, that it was practised in every European country.

Certainly he admitted that in America they would find quite a different state of things in this respeet. But in Europe suet, was the practice,—in Spain, for instance ; especialiy in Hunan& where, though there was no power to press a mall for the Navy, the Government haul power to press for soldiers, and then give the pressed nwu the choice to go on board ship as a sitlor in preference to Nerving inn military caparity. In Russia, also, the power was retained of pressing whole hordes, and by these means alone was the naval service of that nation tilled up.

4. CLAIMS OF THE DISSENTERS.

A number of petitions from the Protestant Disseeters were presented on Monday in the House of Lords, by Lords Dacia:, POLTIMORE, LYTTLETON, GREY, and DURHAM. Lod DURIIA3I said, that he could not concur with those who prayed for a separation of Church and State; but with respect to every other object mentioned in the petitions, he expressed his most hearty assent to the views taken by those who signed them ; and he could not avoid deeply lamenting that the bill then iv ihrougit tile other House l'or the relief of the Dissenters did aot go further. Earl Gasv said, that the measure ulluded to by Lord Durham only embraced one object, and it was a mistake to suppose that no other measures of relief were intended. Ministers had turned their serious attention to this subject. with the hope and intention of giving extensive relief to the Diseeoters, if not entirely removing the objects of complaint. He should, however, in common with Lord Durham, keep stedfirstly in view the necessity of supporting the Established Church. Lord Dreitem expressed his satisfaction at hearing that other measures of relief for the Dissenters were in preparation. In the evening Lord A LTHORP gave notice in the House of Commons, that on Thursday the 7th April he should call the attention of the House to the subject of Church-rates.

5. COMMUTATION OF TITHES.

A long discussion arose in the House of COIOIDODS on Tuesday, on the presentation, by Lord LaaleoroN, of the Devonshire petition for the commutation of tithes, by substituting a tenth part of the valet: of the land as an equivalent for the tithe now collected. Lord Althorp, Lord John Russell, and Mr. Littleton were in their places ; and there was a much fuller attendance of Members generally than is usual at a morning sitting. The prayer of the petition, so far as related to the proposed equivalent of two shillings in the pound, was opposed by Lord E BRINGVON (who acknowledged, however, that it was supported by a majority of the landholders of the country), by Lord JOHN RUSSELL, and Mr. Bur:rests Sir H. WILLOUGHBY, Mr. WILBRAHAM, Mr. DIVETT, Mr. BENETT, Sir ROBERT PEEL, and Mr. Halter:v. Mr. HARVEY insisted that the tithes belonged to the State ; Sir ROBERT PEEL that thi y belonged to the Church : both agreed that the landlord had no right to pocket them. Mr. Reiman supported the prayer of the petition ; and explained a point in which the views of the petitioners had been !Misunderstood.

What they wished was, that the land should be valued as tithe-free in the 6rst instance, and also as being free of rates and taxes ; the value having been ascertained, then a tenth part of that value was to go to the titheowner, subject to the same rates and taxes as the other nine parts. This was a different thing from the tenth part of the rent, which might be very low, as a portion of the art produce, for the use and occupation of the laud.

Colonel SEALE also supported the petition. Twelve years ago, in Devonshire, the tithe was only 2s. 611. in the pound : within the last nine years, it had been raised to 3s : he did not see why it could not row be reduced to 2s., on the same principle on which it had been Sai.4ed to 3s.

After some remarks from Mr. O'Coarreest, Mr. SHEIL, and Mr. Sae:Demi, the petition was laid on the table.

6. PREVENTION OE BRIBERY.

Mr. Hanoiobtained leave, on Tuesday, to bring in a bill to conso. lidate and amend the several acts relating to bribery and the expense of elections. Ile proposed that treating, or money given alter as well as before an election in reference to the votes of electors, should be illegal —that the payments fin. the couveyance of voters to tler poll should be Illegal ; that the time for presenting petitions against a return should be extended to twenty-eight days after the last at of briHery; and that all 0:alt should ho taken by each candidate, that neither directly nor in directly had he at or ivould ht. at! erupt, to procure votes by bribery. Lord Jona 11 esseis. mid Mr. W ISSN spoke in flivour of the measure, without promising support of all the details. :!r. 11 aeens !harms approved of the bill. Mr. IlIME observed that the ballot was

• unquestionably the best mode of extirpating bribely aid corruption.

7. CORRUPT BOROIYGIIS.

DISFRANCHISEMENT OE CARRICKFERGUS AND STAFFORD. The bills for the disfranchisement of these boroughs both passed their secend reading on Wednesday; the first without a division, the eecond by 167 to 5. It remains, however, to be decided in Committee, whether there shall be a total disfranchisement of Carrickfergus, or whether a new constituency shall be formed out of the ten-pound householders. These householders only amount to 105 in number. The number of freemen is 885; of whom 240 received bribes at the List election.

Boaouou or, WARWICK Blue The bill for extending the constitueecy of Warwick to Leamington next came under*discussion, on the motion of Sir RONALD FERGUSON, that the House should resolve itself into a Committee upon the bill. Mr. Hateoste moved as an amendmeet, that a Select Committee should be appointed to inquire into a breach of privilege, which he asserted had been committed in affixing the rames of several persons to a petition from Leamington to that House, praying for incorporation with Warwick. The petition purported to be signed by 410 rate-payers of Leamington ; but it could be proved, that of those persons, 280 could not be found in the town, or upon the rate. The petition was set on foot by members of the Birmingham Political Union. The report of the Committee had been drawn up by Mr. Joseph Parkes: he would ask Sir Ronald Ferguson if it were not so? Sir RONALD, not hearing distinctly, said—" I ant totally ignorant of the getting up of this petition." Mr. HALCOMB mid—" I perceive the gallant General, owing to his deafn .ss, did riot hear what I said : he supposes I referred to the petition." Sir Roarnsu, again misunderstanding the question, said that "he knew nothing of it." Mr. HALCOMB resumed. He said that the individual at the bottom of all this was Air. Joseph Pal kes, who, unfortunately, had the ear of a very high personage in this country.

A desultory debate then ensued. Mr. Halcomb, having been re

peatedly interrupted by groans and cries of "Oh, oh!" complained of this, and particularly of Mr. E. J. Stanley; who, he said, treated bun -with personal insolence. Mr. STANLEY assured Mr. Halcomb that he only meant to testify, in the usual Parliamentary way, his admiration of the eloquence and perseverance with which he advocated the cause of the distresaed boroughs. Mr. GOULBURN interceded more than once for Mr. Halcomb, but with little effect.

The Bill finally went through the Committee, and the,report was received. A Select Committee was then appointed to inquire into the eircumstauces attending the elleged breach of privilege regarding the signatures to the Leamington petition. OISIRAN. • THE LIVERPOOL FREEMEN BILL The

House determined to s.;;) into a Committee on this bill on Wednesday next; as tha hour when it was brought forward last Wednesday was too late for the long discussion which was expected.

MISCELLANEOUS SUBJECTS.

RECORD COMMISSIONERS. Mr. Ht7ME asked Lord Althorp, on Monday, whether any new arrangement had been made respecting the Record Commission ? Most of the appointments were sinecures, and they cost the country 10,000/. a year. Had the office of Chief Keeper been filled up ? Lord ALTHORP could not tell.

GENERAL REGISTRY BILL. Mr. WILLIAM BROUGHAM has obtained leave to bring in a bill to establish a general registry of all deeds and instruments relating to real property in England and Wales.

REGISTRATION Blue Last night, Mr. IV. BROUGHAM gave notice, that on the 22d of April he would move for leave to bring in a bill to establish a registry of all births, deaths, and marriages, in England and Wales.

FOREIGN ENLISTMENT ACT. Leave Was given on Tuesday to Mr. J. A. Murray to bring in a bill for the repeal of this act. The bill, Mr. MURRAY st tted, was the same as the one which was carried through time house a Commons last session. It was read a first time on Wednesday, and will be read a second time on the 31st March.

IRISH Jetty LAW. A motion, on Tuesday, by Mr. O'CossarEts, for leave to bring in a bill to regulate the forming of Petty Juries in Ireland, was opposed by Mr. LrerraeroN and Lord ALTHORP ; who wished the bill of last session for the choosing of special juries to have a fair trial. The motion was withdrawn reluctantly by Mr. O'Connell.

1lor7se Tax. On the motion of' Lord Au-Hoar, on Thursday, a bill to repeal the House-tax was brought it), read a first times and ordered to be read a second time on Monday. Lord A Urlione stated, that this bill would afford relief to the amount of 1,17000/. ; and he preferred repealing this tax rather than the Window. tax, because it would give relief to the occupiers of 62,000 houses, who did not pay a Window-tax.

DCNGARVON Esecnosr. The Speaker informed the House, that he had received a petition against the return of Mr. Jacob for Dungarvon. It was ordered to be taken into consideration on the 15th March.

CASE OF THE BRIGHTON GUARDIAN. Mr. WIGNEY moved on Tuesday, that an address be presented to the King, praying him to remit the two remaining months of imprisomnent in Chelmsford Gaol, out of the six to which Mr. Cohen, the editor of the Briylul a Guardian, had been sentenced. The motion was opposed by Lord Homes, Lords G. and A. LENNOX, Sir C. BURRELL, and Mr. GORING. It Was supported earnestly by Lerd W. Leareoss, Mr. HAWKINS, Mr. C. 111:1.1.r.n, Sir C. RixxT, and Mr. CUBTE:S. Oa a divisive, it was rejected by 58 to 21.

Previous page

Previous page