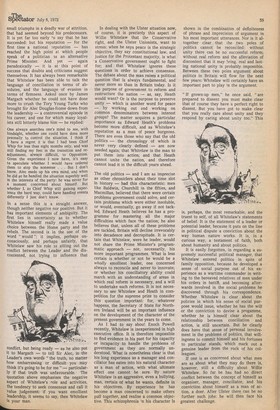

Whitelaw: a man for which season?

Patrick Cosgrave

I remember sitting once, over a few glasses, with William Whitelaw and about a dozen Tory MPs, mainly of the newer vintage. The Tories were in opposition, and the going was tough. Whitelaw had just returned from a trip to the United States and, from what he had heard and read abroad, was of the opinion that the Wilson government was on its last legs. He was surprised to find that his junior colleagues were despondent: the polls had begun to shift against them; things were going badly in the House of Commons; Harold Wilson was handling the opposition with insouciant ease — the catalogue of woes mounted. Whitelaw listened for some time, his craggy face creased ;n sympathetic and hurt attention. Then he began to speak, softly at first, but with increasing volubility and gesticulation. He asked a technical question about the balance of payments surplus of one of those present — a man who is now a junior minister — and got a highly technical answer. He picked one detail out of that answer — "The one I can understand" he pronounced jovially — and began to elaborate on its meaning in terms of popular politics. When he was finished there was scarcely a man present who did not believe that the Tories would win the next election, Ind who could not have walked the plank for Whitelaw.

I remember almost every detail of that convivial scene, yet I can scarcely remember a word of what Whitelaw said. I doubt, indeed, if — though he is capable of profundity — he said anything in any way profound or remarkable. What he did was inject the group with some of his own compulsive vitality. How he did it remains mysterious. Certainly, he has an intimate and natural understanding of the claustro

his five harrowing years as Chief Whip; the second enables him to attach men to him, and cause them to hesitate before they give him trouble, pain or offence. But the sum of his obvious qualities does not add up to the political force that he is. Nor does that sum take account of two other important aspects of his character: his energy and his vulnerability.

The energy radiates from him. When he held his first briefing of junior ministers and advisers on taking office as Secretary of State for Northern Ireland he expressed his concern that they might feel borne down by their task and in consequence become entrapped in the mesh of despair and ineffectiveness that lay over Ulster. "It may be that the situation is hopeless," he said, "but we gain absolutely nothing from admitting that, or even considering it. We must remain cheerful, and we must try to preserve an agreeable social life. If we don't keep our own spirits up, how can we get Irish hopes up? And the fact that we are cheerful and hopeful may be an important political fact in itself." The vulnerability is less evident, but there were bad moments as Chief Whip when he hated the job, because it took so much spirit out of him. There were, too, the flashes of violent temper, especially after arduous sessions with particularly recalcitrant would-be rebels. And, worst of all, there were the moments in opposition when the party and its leadership seemed to flounder and his face would appear to crumple up into its component parts with gloom and near-despair. The energy and the vulnerability combined make him more effective: for when so large and vital a man can sag and then recover completely, those he is seeking to influence feel selfish and mean if they do not respond.

Whitelaw came into Parliament in 1955. His first job was as Parliamentary Private Secretary to Peter Thorneycroft. He was then joint secretary of the 1922 Committee, secretary of the Horticulture and Transport Committees and an officer on other committees as well. He spent two years as Parliamentary Secretary to the old Ministry of Labour, was then Deputy Chief Whip and, from November 1964 until the last general election, Chief Whip. His ultimately brilliant success as an organisation man convinced those looking at his career with hindsight, and noting his bonhomie and gregariousness, that he was made for this political role. Yet his natural ebullience of temperament, and his proneness to emotionalism and temper might surely have disqualified him. He has often hungered for what his admirers called a " real " job, the challenge of detail, action and a great department of state; and he had to impose the severest curbs of self-discipline on his nature to retain both effectiveness and sanity during his time as Chief Whip. When the rumour was going around that, if elected, Heath would make him Lord President of the Council and Leader of the House of Commons — a sort of superior Chief Whip, aF one fan disgustedly put it — a senior Labour minister expostulated to his Conservative Shadow: "Ted must be mad. Willie won't be able to take much more of that conciliatory stuff, and you'd need him in a big job." The selfdiscipline and self-control which Whitelaw had cultivated had, nonetheless, to be carried on to the business of organising the government's legislative programme as Leader of the House.

It did not last. Though it was conveniently forgotten in the glow of approval which greeted the appointment to the Northern Ireland Office of a senior, widely popular, and liberal-minded politician, the gilt had been wearing somewhat thin on the gingerbread of Whitelaw's reputation as a man of conciliation during his last days as Leader of the House. He had openly lost his temper more than once, been caught out of his facts by the opposition on one embarrassing occasion, and begun to lose that acceptance on both sides which is essential for a man in his job. It was not just that he was stale: it was more than he had been playing for so long a role at odds with his natural expressiveness and hunger for action — a role at odds with his real nature — that his inner self was becoming difficult if not impossible to curb.

It was, therefore, a supreme irony that when Whitelaw got his " real " job it was one requiring the exercise of those talents which were rapidly leading him to frustration. But the end he was required to serve was far more immediate, more critical, more dangerous. It was also the case that a great deal of practical administrative and legislative work needed to be done. Whitelaw's immediate contribution was to seize on the strategic point in the situation — the necessity to restore peace — and devote himself to that, while his junior ministers proceeded with the work of reconstruction, even before the killing stopped. "The man's bloody marvellous," an Irish journalist friend told me as we approached yet another critical weekend. "He's had a rabbit out of the hat every day for the last week." Once again Whitelaw's reputation as an adroit and brilliant manoeuvrer began to boom: his humour, intelligence, humanity, and restraint were again emphasised, while one by one he achieved measures of success, small triumphs in a deadly war of attrition, that had seemed beyond his predecessors. It is yet far too early fo say that he has succeeded: but his reputation — for the first time a national reputation — has reached the high point a; which people speak of a politician as an alternative Prime Minister. And yet — again paradoxically — it is at this point of success that doubts and criticisms suggest themselves. It has always been remarkable that Whitelaw has been able to talk the language of conciliation in terms of absolutes, and the language of evasion in terms of firmness. Asked once by James Margach whether he could not have done more to crush the Tory Young Turks who brought Sir Alec Douglas-Home down from the leadership — a controversial episode in his career, and one for .which many loyalists still bitterly blame him — he replied: One always searches one's mind to see, with hindsight, whether one could have done more prsonally to control the situation. I think if I have a regret it is that I had been Chief Whip for less than eight months only, and was still finding my feet in the transition and readjustment, always difficult, to Opposition. Given the experience I now have, it's easy to speculate whether I would have ordered them to stop the nonsense . . . But I don't know. Alec made up his own mind, and when he did so he handled the situation superbly well in the interests of the party: he was never for a moment concerned about himself. But whether I, as Chief Whip still gaining experience the hard way, could have handled events differently I just don't know.

In a sense this is a straight answer, though neither negative nor positive. But it has important elements of ambiguity. The first lies in uncertainty as to whether Whitelaw himself really made a value choice between the Home party and the rebels. The second is in the use of the word "would ": it implies, perhaps unconsciously, and perhaps unfairly, that Whitelaw saw his role as sitting out the conflict between the Leader and the discontented, not trying to influence that

conflict, but being ready — as he also put It to Margach — to tell Sir Alec, in the Leader's own words "the truth, no matter how embarrassing or difficult you may think it's going to be for me " — particularly if that truth was unfavourable. The quotation above emphasises the negative aspect of Whitelaw's role and activities, the tendency to seek consensus and call it value judgement: if you want emollient leadership, it seems to say, then Whitelaw 15 your man. In dealing with the Ulster situation now, of course, it is precisely this aspect of Willie Whitelaw that the Conservative right, and the Ulster Unionists, want to stress: when he says peace is the strategic objective, they say constitutional law, and justice for the Protestant majority, is what a Conservative government ought to fight for; and that Whitelaw ignores these questions in order to achieve consensus. The debate about the man raises a political question that is always fundamental, and never more so than in Britain today. Is it the purpose of government to reform and restructure the nation -as, say, Heath would want? Or is the purpose to preserve unity — which is another word for peace — by working out and working on common denominators between interest groups? The matter acquires a particular importance as Edward Heath's problems become more difficult, and as Whitelaw's reputation as a man of peace burgeons. There are even those who say that the old politics — the chronology of which is never very clearly defined — are now needed, again; that Whitelaw is the man to put them into action; and that Heath cannot unite the nation, and therefore cannot lead it in the difficult years ahead.

The old politics — and I am as imprecise as other chroniclers about their time slot in history — had this characteristic: men like Baldwin, Churchill in the fifties, and Macmillan, believed that there were certain problems government could solve, and certain problems which were either insoluble, or would, eventually, go away if not tackled. Edward Heath believes he has a programme for mastering all the major difficulties which face the nation; he also believes that, unless all of these problems are tackled, Britain will decline irrevocably into decadence and decrepitude. It is certain that Whitelaw, were he leader, would not share the Prime Minister's programmatic approach — nor, necessarily, his more important programmes. What is less certain is whether or not he would be a wholly emollient leader, one concerned always to reconcile and never to innovate; or whether his conciliatory ability could march with an understanding of areas in which real reform is necessary, and a will to undertake such reforms. It is not necessary to see Whitelaw and Heath in competition for the supreme prize to consider this question important: for, whatever happens, the Secretary 3f State for Northern Ireland will be an important influence on the development of the character of the present government in the years to come.

As I had to say about Enoch Powell recently, Whitelaw is inexperienced in high executive office. It is therefore impossible to find evidence in his past for his capacity or incapacity to handle the problems of government as they are normally understood. What is nonetheless clear is that his long experience as a manager and conciliator has eaten into his natural character as a man of action, with what ultimate effect one cannot be sure. By nature Whitelaw is an aggressive, even a bullying, man, certain of what he wants, definite in his objectives. By experience he has become a man concerned to make others pull together, and realise a common objective. This schizophrenia ;n his character is

shown in the combination of definiteness of phrase and imprecision of argument in his most important utterances. Nor is it altogether clear that ihe two poles of politics cannot be reconciled: without unity there can be no successful reform; without real reform and the alleviation of discontent that it may ?ring. real and lasting national unity is probably impossible. Between these two poles argument about politics in Britain will flow for the next few years: Whitelaw will certainly have an important part to play in the argument.

" If grown-up men," he once said, "are prepared to dissent you must make clear that of course they have a perfect right to dissent. But you have got to make clear that you really care about unity and they respond by caring about unity too." This is, perhaps, the most remarkable, and the truest to self, of all Whitelaw's statements of belief. It is the statement of a leader or potential leader, because it puts on the line in political dispute a conviction about the way human nature works. It is, in a curious way, a testament of faith, both about humanity and about politics.

It is easily forgotten, in regarding a supremely successful political manager, that Whitelaw entered politics in spite of family opposition, because he developed a sense of social purpose out of his experience as a wartime commander in writing to the bereaved relatives of men under his orders in battlt, and becoming afterwards involved in the social problems he discovered through his correspondence. Whether Whitelaw is clear about the policies in which his sense of social purpose would issue, whether he has the will or the conviction to devise a progamme, whether he is himself clear about the relationship between conciliation and action, is still uncertain. But he clearly does have that sense of personal involvement in the problems of politics, that willingness to commit himself and his fortunes to particular stands, which mark out a genuine leader from the ruck of his colleagues.

If one is as concerned about what men are as about what they may do there is, however, still a difficulty about Willie Whitelaw. So far he has had no direct conflict between the concept of himself as organiser, manager, conciliator, and his conviction about himself as a man of action, a doer. After Ulster there can be no further such jobs: he will then face his greatest challenge.

Previous page

Previous page