Recent books of photographs

Christopher Howse In England by Don McCullin (Cape, £35) is, as might be expected, more gritty than pretty. Yet it is approachably humane compared with his famous war photography, where from Vietnam to Beirut the horrors are as terrible as Goya's.

McCullin escaped the London gangland of Finsbury Park by means of the photograph that forms the frontispiece of this book. It shows The Guvnors, a gang of young men with whom he had grown up, posing in the sun in their sharp Fifties Sunday suits and thin ties on the beams of a half demolished house. One of them was hanged after a policeman was knifed; McCullin sold his picture to the Observer, and set off into a wider world of war.

In England represents the gaps between foreign assignments: potato-pickers in Hertfordshire in 1961, looking for all the world like Romanian migrants today; in Whitechapel, from the same year, a headscarfed homeless woman sitting on a bed next to shabby suitcases opposite her five grubby children on a bunk; from Liverpool in the 1970s a child running over shiny black streets, between spaces where houses once stood.

Don McCullin excels in placing lone figures in desolate industrial landscapes. A solitary cyclist, leaving tracks in the coaldust by a railway line at a pithead in Doncaster (1967), stares from beneath a crooked black beret, as he grasps the handlebars, a lit cigarette deftly poised between two fingers. But even a drunk, disturbed down-and-out collapsed near an open fire in Spitalfields (the kind we used to call meths-drinkers, who seem now almost extinct) retains a human individuality through McCullin's lens.

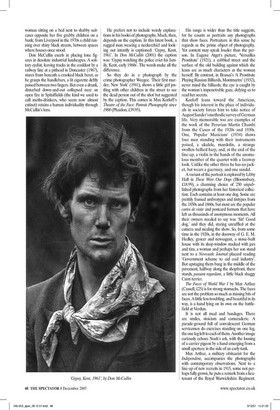

He prefers not to include wordy explanations in his books of photographs. Much, then, depends on the caption. In this latest book, a rugged man wearing a neckerchief and looking out intently is captioned: 'Gypsy, Kent, 1961'. In Don McCullin (2001) the caption was: 'Gypsy watching the police evict his family, Kent, early 1960s'. The words make all the difference.

So they do in a photograph by the crime photographer Weegee. 'Their first murder, New York' (1941), shows a little girl jostling with other children in the street to see the dead person out of the shot but suggested by the caption. This comes in Max Kozloff's Theatre of the Face: Portrait Photography since 1900 (Phaidon, £39.95).

His range is wider than the title suggests, for he counts as portraits any photographs that show faces. Portraiture in this sense he regards as the prime object of photography. Yet context may speak louder than the person. In Eugene Atget's picture, 'Versailles Prostitute' (1921), a cobbled street and the surface of the old building against which she leans are as much characters as the woman herself. By contrast, in Brassai's 'A Prostitute Playing Russian Billiards, Montmartre' (1932), never mind the billiards, the eye is caught by the woman's impenetrable gaze, defying us to read her secrets.

Kozloff leans toward the American, though his interest in the place of individuals in society forces him to take notice of August Sander's methodic survey of German life. Very memorable too are examples of the work of the Peruvian Martin Chambi from the Cusco of the 1920s and 1930s. One, 'Popular Musicians' (1934) shows four men standing with their instruments poised, a ukulele, mandolin, a strange swollen-bellied harp, and, at the end of the line-up, a violin in the hands of the anomalous member of the quartet with a faraway look. Unlike the other three he has no jacket, but wears a guernsey, and one sandal.

A variant of the portrait is explored by Libby Hall in These Were Our Dogs (Bloomsbury, £18.99), a charming choice of 250 unpublished photographs from her historical collection. Each contains at least one dog. Some are prettily framed ambrotypes and tintypes from the 1850s and 1860s, but most are the popular cartes de visite and postcard formats that have left us thousands of anonymous moments. All their owners needed to say was 'Sit! Good dog,' and they did, staring unruffled at the camera and stealing the show. So, from some time in the 1920s, in the doorway of G. E. M. Hedley, grocer and newsagent, a stone-built house with its shop-window stacked with jars and tins, a woman and perhaps her son stand next to a Newcastle Journal placard reading 'Government scheme to aid coal industry'. But upstaging them bang in the middle of the pavement, halfway along the shopfi-ont, there stands, passant regardant, a little black shaggy Cairn terrier.

The Faces of World War I by Max Arthur (Cassell, £25) is for strong stomachs. The faces are not the problem so much as missing bits of faces. A little less troubling, and beautiful in its way, is a hand lying on its own on the battlefield at Verdun.

It is not all mud and bandages. There are smiles, stoicism and camaraderie. A parade-ground full of convalescent German servicemen do exercises standing on one leg, the one leg left to each of them. Another image curiously echoes Noah's ark, with the loosing of a carrier pigeon by a hand emerging from a small aperture in the side of an early tank.

Max Arthur, a military obituarist for the Independent, accompanies the photographs with contemporary observations. Next to a line-up of new recruits in 1915, some not perhaps fully grown, he puts a remark from a lieutenant of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment.

'When they came to us they were weedy, sallow, skinny, frightened children — the refuse of our industrial system. After six months of good food, fresh air and physical exercise they changed so much their mothers wouldn't recognise them.' Nor, for many, later.

The BBC4 series The Genius of Photography reflects a wide interest in the history of photography as well as the history it depicts. Roger Taylor, in Impressed by Light: British Photographs from Paper Negatives, 1840-1860 (Yale, £45) captures the impact of surprise that the first photographs made. When in 1844 Henry Fox Talbot published The Pencil of Nature a part-work of his 'sun-pictures', he wisely included a Notice to the Reader in the second instalment to remove misunderstandings: 'The plates of the present work are impressed by the agency of Light alone, without any aid whatever from the artist's pencil.'

Unlike the daguerreotype and its successors, the paper-negative calotypes could produce multiple copies. And they were less cumbersome and fragile than the glass negatives that appeared in the 1850s. Much depended on the printing, and the best showed the Victorians things that they liked in images they had never imagined. So, among the 118 full-page examples that Taylor reproduces, there is a picturesque farmyard at Compton, Surrey (1852), by the admired Benjamin Brecknell Turner, in which the shaven sides of the haystack can almost be felt like a cat's back. Or, in 1847 sitting beside the basaltic columns of Fingal's Cave, John Muir Wood catches a mutton-chopped traveller in coat and tall silk hat. In their day these photographs were vicarious tourism, and as the name calotype was meant to suggest, they were beautiful pictures, and remain so to us.

Previous page

Previous page