A Dictionary that is New

WEBSTER'S NEW WORLD DICTIONARY. (Macmillan, 70s.)

THE newness of any dictionary, especially of English, is compara- tive: most new dictionaries are not new at all, being mere adapta- tions or modifications. We in Britain and the British dominions and colonies are so fortunate as to possess the greatest dictionary ever published anywhere; The Oxford English Dictionary merits that adjective secondarily and incidentally by its size and primarily and purposely by its quality, for, although it owes something to Littre's dictionary of French, it owes far more to the planners and editors, two of the latter. Sir William Craigie and Dr. C. T. Onions, being still with us. 'The OED' probably owes a little to Noah Webster's American Dictionary of the English Language, published in 1828 and revised by its remarkable editor and then by a succession of scholars, until, in 1934, there appeared the splendid recension of Webster's New International Dictionary. In his turn, Webster had owed much to Dr. Johnson, Johnson to Nathan Bailey, Bailey to the earlier lexicographers.

What particularly concerns us here is that genus of American dictionary which consists of works standing roughly midway between 'the Shorter Oxford' and 'the Concise Oxford' : something to which we have no native counterpart in Britain. Many curious and prudent persons have, of course, sensibly procured a copy either of Webster's Collegiate Dictionary or of The American College Dictionary, which, not misleadingly described as 'a larger Concise,' is slightly less literary, but certainly no less scholarly than that exemplary work.

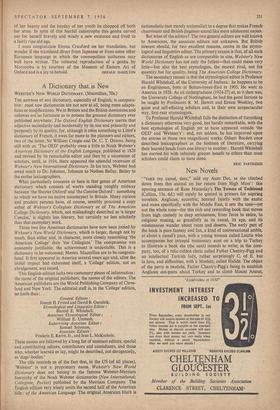

Those two fine American dictionaries have now been joined by

Webster's New World Dictionary, which is larger, though not by much, than either and, in character, more closely resembling 'the American College' than 'the Collegiate.' The compromise was eminently justifiable; the achievement is undeniable. This is a dictionary to be welcomed; Messrs. Macmillan are to be congratu- lated. It first appeared in America several years ago and, after the initial impact had exhausted itself, a 'College' edition, not an abridgement, was issued.

This English edition lacks two customary pieces of information : the name of the original publishers; the names of the editors. The American publishers are the World Publishing Company of Cleve- land and New York. The editorial staff is, in the 'College' edition, set forth thus : General Editors : Joseph H. Friend and David B. Guralnik. Etymological and Linguistics Editor :

Harold E. Whitehall.

Associate Etymological Editor: William E. Umbach.

Supervising Associate Editor : Samuel Solomon. Associate Editors : Frederic E. Reeve, Jr., and Jean L. McKechnie.

These names are followed by a long list of assistant editors, special and contributing editors, contributors and consultants, and those who, whether learned or lay, might be described, not derogatorily, as `dogs'-bodies.'

The title reminds us of the fact that, in the US (of all places), 'Webster' is not a proprietary name. Webster's New World Dictionary does not belong to the famous Webster-Merriam hierarchy of the Noah Webster dictionaries (New International; Collegiate; Pocket) published by the Merriam Company. The

English edition very wisely omits the second half of the American title : of the American Language. The original American blurb is

nationalistic (not merely nationalist) to a degree that makes French chauvinism and British jingoism sound like mere adolescent excess.

But what of the editors? The two general editors are well known to Americans, the associate editors not unknown. But British interest should, for two excellent reasons, centre in the etymo- logical and linguistics editor. The primary reason is that, of all such dictionaries of English as are comparable in size, Webster's New World Dictionary has not only the fullest—that could mean very little—but also the best etymologies, the nearest rival, not for quantity but for quality, being The American College Dictionary.

The secondary reason is that the etymological editor is Professor Harold Whitehall, of the University of Indiana : he happens to be an Englishman, born at Bolton-lower-End in 1905. He went to America in 1928. As an undergraduate (1924-27) at, as it then was, the University College of Nottingham, he had the good fortune to be taught by Professors R. M. Hewitt and Ernest Weekley, two quiet and self-effacing scholars and, in their own unspectacular way, first-rate etymologists.

To Professor Harold Whitehall falls the distinction of furnishing a dictionary otherwise very good, but hardly remarkable, with the best etymologies of English yet to have appeared outside 'the OED' and 'Webster's': and, not seldom, he has improved upon the entries in those two magnificent works. Osbert Burdett once described lexicographers as the hodmen of literature, carrying their learned heads from one library to another : Harold Whitehall has carried his with infinitely greater benefit to others than most scholars could claim to have done.

ERIC PARTRIDGE

Previous page

Previous page