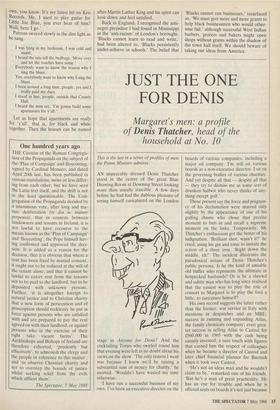

JUST THE ONE FOR DENTS

Margaret's men: a profile

of Denis Thatcher, head of the

household at No. 10

This is the last in a series of profiles of men the Prime Minister admires.

AN impeccably dressed Denis Thatcher stood in the centre of the great Blue Drawing Room at Downing Street looking more than usually irascible. A few days before he had had the dubious pleasure of seeing himself caricatured on the London stage in Anyone for Denis? And the cocktailing Tories who swirled round him that evening were left in no doubt about his views on the show. 'The only reason I went was because I knew we'd be raising a substantial sum of money for charity,' he snorted. 'Wouldn't have wasted my time otherwise.

'I have run a successful business of my own. I've been an executive director on the

boards of various companies, including a major oil company. I'm still on various boards as a non-executive director. I sit on the governing bodies of various charities. And yet despite all that — despite all that — they try to dismiss me as some sort of drunken halfwit who never thinks of any- thing except golf.'

Those present say the force and poignan- cy of his declamation were marred only slightly by the appearance of one of his golfing chums who chose that precise moment to butt in and recall a supreme moment on the links. Temporarily, Mr Thatcher's enthusiasm got the better of his indignation. 'Brilliant shot, wasn't it?' he cried, using his gin and tonic to imitate the action of a three iron. 'Right down the middle, eh?' The incident illustrates the paradoxical nature of Denis Thatcher's public persona. Is he the kind of amiable old buffer who represents the ultimate in henpecked husbands? Or is he a shrewd and subtle man who has long since realised that the easiest way to play the role of consort to Margaret is to play the fool a little, to caricature himself?

His own record suggests the latter rather than the former: war service in Italy with mentions in despatches and an MBE: success in running and expanding Atlas, the family chemicals company; even grea- ter success in selling Atlas to Castrol for £560,000 in 1965 with the cash being cannily invested; a sure touch with figures that earned him the respect of colleagues when he became a director of Castrol and later chief financial planner for Burmah when it took over Castrol.

'He's not an ideas man and he wouldn't claim to be,' remarked one of his friends. 'But he's a man of great practicality. He has an eye for trouble and when he is offered seats on boards it's not just because he is the Prime Minister's husband. He'll often put his finger on something that his colleagues just haven't seen.

'Nor are his business commitments merely to fill in time. The Thatchers are among the biggest entertainers Downing Street has ever seen and much of it is paid for out of his private account. So he needs to go on being the breadwinner.'

Denis Thatcher's career in business may not have been anything like as outstanding as his wife's has been in politics but his achievements are respectable enough and far more considerable than those of the aging and inept Hooray Henry he is often imagined to be.

Yet sometimes he seems positively to foster the image of a downtrodden male whose only comforts in a world of matriar- chal might are golf and gin. Take, for example, the time when Downing Street's cocktail chatter turned to the rearing of children and, in particular, to twins like his own Mark and Carol. 'Never had any trouble with my two,' he said proudly. 'They always got on so well together. I can think of only one occasion when we had a problem. On the road to Portsmouth, it was.' A waitress bearing a tray weighed down with every conceivable type of drink interrupted to ask if she could replace his empty glass. Mr Thatcher gave the tray a disparaging glance and shook his head.

'D'you think you could get me one of my specials, m'dear?' he coaxed. 'You know how I like it, don't you? Without lemon.' A few moments later, with a tumblerful of lemonless liquid to hand, he continued his saga.

'On the road to Portsmouth, it was,' he said. 'Carol and Mark started bickering in the back. So I put my foot down. I stopped the car and I said: "Right, you three — get out." So they got out of the car. And I said: "Right, Margaret! Deal with 'em.—

Those privileged to receive this insight into the private life of the Thatchers came away convinced that Denis must have been sending himself up. But those who know him well say part of his charm is that he has no such hidden depths. 'Denis isn't the type to send himself up,' said one. 'The secret of Denis is that he's an old-fashioned Englishman who belongs to an era that has long since passed away. He knows it, too. But he's buggered if he's going to change. Of course he'd tell Margaret to sort out the children. In his book. dealing with the children is the wife's responsibility, not his.'

Another close Thatcher-watcher com- mented: 'He's very far from being a buffoon but he is a bit of a buffer.' This assessment of Denis Thatcher as an able but somewhat blinkered traditionalist whose old-style courtesy is matched by a strong streak of male chauvinism is borne out by even his closest cronies. This raises the question of what it was that pretty Margaret Roberts, with her rather radical ideas and her boundless ambition, found so

attractive about him back in 1951 when she married him. After all, the reason Denis Thatcher is not just another successful but unknown businessman is that he persuaded one of the most remarkable women of the century to become his wife.

Perhaps it was the very fact that he was such a traditional type that appealed to her. The truth is Mrs Thatcher may be a remarkable politician but, where marriage and romance are concerned, her instincts are indistinguishable from those of millions of other women. As one denizen of Down- ing Street put it: 'When it comes to men, she goes for Mills and Boon heroes every time.'

Denis Thatcher, whatever his shortcom- ings in terms of intellectual brilliance or contemporary ideas, fits the Mills and Boon romantic stereotype to a T. He is tall, broad-shouldered, well dressed, charming, self-assured, fiercely protective of those he loves, loyal, energetic and rich. Given her Victorian ideals, it's small won- der that she fell for him.

Her Mills and Boon instincts have stood her in good stead — at least in the matter of choosing a husband. A study of some of America's most successful businesswomen found that nearly all of them had relied heavily on the help and encouragement of an older man, whether father, boss or husband. Denis, who is ten years older than his wife — and will be 73 on 10 May — has provided that same backing, both financial and moral, for Mrs Thatcher. Without him as a base, she might never have made it to the top.

Even now, when she is the most power- ful woman in the land, his desire to protect her is strong. If her phone calls show signs of becoming lengthy and acrimonious, he has no hesitation about interrupting with a peremptory shout of: 'Right, Margaret. That's enough of him.' It is an order, too, not a comment. He may not have the faintest idea which member of the Cabinet she's arguing with but he's darned if he's going to have the blighter upsetting his wife.

When crises loom on the political front and she starts becoming tearful — a not

'Of all people, P&O should have left the doors open for negotiation.'

infrequent occurrence — he is always there to comfort her and to put things into perspective with a few well chosen words. Usually along the lines of, 'Sod the lot of them.'

A man with less self-confidence would not be willing or able to play such a role. Some might say his self-confidence springs from a certain Blimpishness of outlook. Be that as it may, nobody can accuse Mar- garet's man of being a wimp. She may be Prime Minister but he is head of the family.

A newspaper once attributed a series of damning comments about the Thatcher family to one of her advisers. The young man had not said any of the things he was quoted as saying but he was terrified that the Prime Minister would be deeply upset just the same. What should he say to her? An older and wiser colleague told him not to say anything to her at all. The invented quotes constituted a personal not a politic- al attack and any explanation should be sent to the head of the family. Denis, a punctilious letter writer, replied by return thanking the young man for his note, assuring him that it was quite unnecessary and insisting that he come for tea. Mar- garet, added Denis firmly, would be look- ing forward to seeing him.

Although outspoken in private about his own, right-wing views, Denis Thatcher has always resisted the temptation to try to influence his wife's political decisions. It may be that the day-to-day realities of power politics hold little appeal for him. In any event the closest he comes to giving the Prime Minister the benefit of his political opinions is in the mornings when they are listening to the Today programme on BBC Radio Four. 'Outrageous bloody pinkoes,' he'll roar. 'Why don't they go and live in bloody Moscow?'

But such comments hardly rank as poli- tical interference. As one of his cronies remarked: 'Which of us doesn't say that to his wife in the morning? Mind you,' he added, 'there's nothing wet about Denis.'

Some would say that one of the least attractive sides of Denis Thatcher is his sympathy for white South Africa. But though he is more than capable of seeing the battle against apartheid in terms of 'the colonials getting uppity again', with him prejudice never takes precedence over good manners. And the 'colonials', as he calls them, are not immune to his charm.

It is said that at the height of the row over sanctions against South Africa, the leader of an African state was calling publicly for Mrs Thatcher's head while privately ringing Downing Street to inquire if Mr Thatcher would be free for a round of golf at the Commonwealth Conference in Canada. (Unsurprisingly, in the circum- stances, he did not feel able to accept the invitation.) There are two ways in which, by com- mon consent. Denis is held to have the advantage over his wife. One is in judging people. He is far more perceptive than she advantage over his wife. One is in judging people. He is far more perceptive than she is and it is the one area where he occa- sionally expresses an opinion and where she always listens. The second is his sense of humour — a commodity with which she is not overendowed.

The Thatchers spend Christmas at Che- quers, going to church in the morning and returning to the house for drinks at noon sharp. But one year the sermon went on so long they were a good 20 minutes late in getting home. `Ah well,' remarked Denis, as they left the church, 'There's one priest who doesn't want to be bishop.'

Those near to him say that behind the bonhomie lies an essentially lonely man. One who has known him longest reflected sadly: 'He has many, many friends and a huge number of private invitations but that's not quite the same as being with your wife at weekends or in the evenings. And of course she is always working. He's not a man to make a nuisance of himself to his cronies and I think there's a good deal of loneliness in his life.

'Mind you, any regrets are tempered by his great pride in her achievements. And though he used to grumble about how nice it would be to retire, he's given that up now. I suppose he realises that he's got a life sentence.'

Previous page

Previous page