TREASURY SWITCH

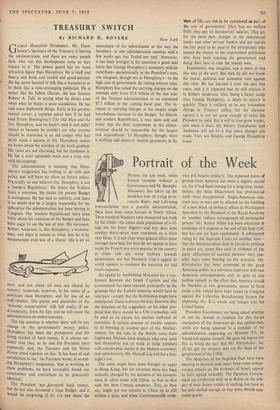

By RICHARD GEORGE MAGOFFIN HUMPHREY, Mr. Eisen- hower's Secretary of the Treasury, is leaving the administration, and there are many people here who rue this development even as they rejoice in it. The palace guard has no more attractive figure than Humphrey. He is bluff and hearty and brisk and candid and good-natured. He has never learned to talk like a bureaucrat or to think like a vote-scrounging politician. He is rather like his fellow Ohioan, the late Senator Robert A. Taft, in saying what he thinks even when what he thinks is quite scandalous. He has said some deplorable things. Early in his govern- mental career, a reporter asked him if he had read Ernest Hemingway's The Old Man and the Sea. Humphrey said he hadn't read it and didn't intend to because he couldn't see why anyone should be interested in an old codger who had never made a success in life. Humphrey makes no bones about his worship of the bitch goddess. His views are not charming, but his frankness is. He has a most agreeable smile and a crisp way with the language.

The administration is insisting that Hum- phrey's resignation has nothing to do with past policy and will have no effect on future policy. Practically no one believes this. Humphrey is not a 'modern Republican.' He thinks the Welfare State is nonsense. He thinks the present Budget is outrageous. He has said so publicly, and there is no doubt that he is largely responsible for the difficulties the administration has been having in Congress. The `modern Republicans' have been bitter about his criticisms of the Budget and have been eager to see the last of him. His successor, Robert Anderson, is, like Humphrey, a business- man, and there is reason to think that he is by temperament even less of a liberal. (He is an oil man, and not many oil men are liberal by nature.) Anderson, however, is far more of a politician than Humphrey and far less of an individualist. The pieties and platitudes of the `dynamic conservatives' will .fall easily, if un- dynamically,.from his lips, and he will cause the administration no embarrassment.

The big question is whether there will be any change in the government's money policy. Humphrey has been the protagonist and the living symbol of hard money. It is almost cer- tainly true that, as he and the President have repeatedly said, the Treasury and the White House stood together on this. `It has been of real satisfaction to me,' the President wrote, in accept- ing Humphrey's resignation, `that in working on these problems, we have invariably found our conclusions and convictions to be practically identical.'

The President has 4favoured hard money, but he has also favoured a huge Budget, and it would be surprising if he did not share the annoyance of his subordinates at the way the Secretary, as one administration member said a few weeks ago, has 'fouled our nest.' Moreover, it has been brought to his attention a good deal lately that George Humphrey's monetary policies contribute—paradoxically in the President's eyes, one imagines, though not in Humphrey's—to the high cost of government. By raising interest rates, Humphrey has raised the carrying charges on the national debt from $5.8 billion in the last year of the Truman administration to an estimated $7.3 billion in the coming fiscal year. The in- crease in carrying charges is the largest single non-defence increase in the Budget. To liberals and modern Republicans, it may seem odd and ironic that the chief economiser in the admin- istration should be responsible for the largest new expenditures. To Humphrey, though, there is nothing odd about it; interest payments, in his view of life, are not to be considered as part of the cost of government. They buy no welfare frills; they pay no bureaucrats' salaries. They go, for the most part, straight to the commercial banks and other private lenders and are merely the fair price to be paid to the enterprisers who loaned the money to the improvident politicians who have been running the government and doing their best to ruin the money men.

Eisenhower, one imagines, saw it more or less this way at the start. But then he did not knoi the moral, political and economic case against this view. He has learned it over the past five years, and it is expected that he will explain it to Robert Anderson, who, being a faster study than George Humphrey, is likely to absorb it quickly. There is unlikely to be any immediate change in Treasury policy, for the clamour against it is not yet great enough to cause the President to yield. But it will in time grow louder, and when it does, the Messrs. Eisenhower and Anderson will see to it that some changes are made. They are flexible, and George Humphrcy is not.

Previous page

Previous page