Six,—'Do people really think, for instance, that this country is

the worse off for having no national Paris-Match or Der Spiegel?' asks Malcolm Ruther- ford; and then goes on to assert that if anyone does, he shouldn't. I do, and I'd like to say why.

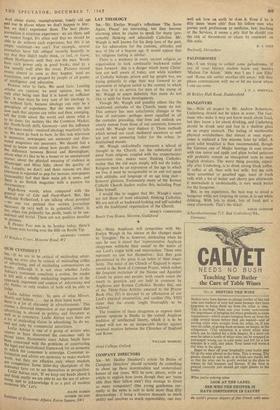

Pictures represent instants in time rather than generalisations over a period of time. Where one example clinches an argument they do a better job than words. Take Sharpeville. Ian Berry's photo- graphs show running unarmed people being shot in the back by policemen, armed with automatic weapons, standing on the roofs of armoured vehicles. Nothing qualifies these pictures. They condemn a regime, and the condemnation is irrefutably just. To argue as a consequence that pictures are so powerful that they are always misleading is saying that no photographer and no editor is honest and knowledgeable enough to weigh the facts and select the pictures that represent the facts. Such an accu- sation is refuted by the existence of Tom Hop- kinson.

Pictures are representations rather than descrip- tions of experience. Without photojournalism, we

old age and

war in places where we don't happen to live: but we don't experience them. The best photo- journalism is vicarious experience: we are there, and we cannot forget. It's often said that we should be able to do without such experience; but this is an empty sentiment—we can't. For example, several Journalists have felt obliged recently honestly to say that they didn't really think, cr feel, or know, about Hartlepools until they saw the men. Words have such power only in good books, read by a few usually well after the event. Pictures record events almost as soon as they happen, need no translation, and are grasped by people of all grades of intelligence and education. Pictures refer to facts. We need facts. Leading articles are opinion; we need opinion, too, but only after being sure that it is based on sufficient fact. A man must be very sure of his ideology to do without facts, because ideology can only be a precipitate of experience. But the times are not now such that anyone can retire and then, emerging, tell the truth about the world and about what is to be done. On matters like the Common Market, the North-South drift, Germany—and the influence of the mass media—received ideology manifestly fails us. We must go back to facts. In this task television is necessary, newspapers are necessary and illus- trated magazines are necessary. We should feel a need to know more about how people live; about the difference between Bristol and Birmingham; about what it's like to be a turner or an unemployed riveter; about the physical meaning of violence in Mississippi and Moss Side; about the quality of life. Largely, we don't, and three reasons are that television is regarded as pap for morons, newspapers (reasonably) feel that their main job is news, and ,nerc is no British magazine with a passion for documentary. High-flown words, when compared with the general run of Life and Paris-Match. But, like Malcolm Rutherford, I am talking about potential —no one can pretend that written journalism Measures up very well to its potential, either; it, too, when run primarily for profit, tends to be sen- sational and trivial. These are not qualities peculiar to pictures.

be Picture Post was in its heyday today, there'd ne fewer men turning over the filth on Bootle Tip.

33 laf • 33 laf •

Previous page

Previous page