The Economy

Insurance Investment and the State

By NICHOLAS DAVENPORT

THE parts of the City most anxiously awaiting the October election result are the board rooms of the life insurance com- panies. As the Labour Party has dedicated itself to growth, which implies in- creasing the amount of the national income devoted to investment, the next Labour Government will be keen to direct that investment into the most desirable channels for the promotion of growth and in particular the growth of the manufacturing industries which can swell the export trade and cut down the ,volume of imports. The present laissez-faire system, which allows private savings to be channelled through the insurance com- panies and pension funds into the capital market without any direction at all, leads to a lot of wasteful investment and—with the help of in- discriminate investment allowances—to what Ian Little has described as 'higgledy-piggledy' growth. And it ends up in a balance of payments problem which is likely to become increasingly worse. For this reason the Labour Party pamphlet Signposts for the Sixties emphatically declared that 'a greater control over the invest- ment policies of pension funds and private in- surance companies' would be required. It is said that Mr. Harold Wilson favours the setting-up of some form of central committee to co-ordinate and direct institutional investment policy.

The boards of the insurance companies are in a vulnerable position partly because they are handling increasingly large funds the investment of which a 'planned economy' could not leave to chance, partly because they confess to having no investment policy at all other than the in- crease of their companies' income required by their actuaries. Last year their 'new money' available for investment amounted to £580 mil- lion, while the pension funds contributed a fur- ther £320 million, a total of £900 million. The amount of new business capital directly raised in the capital market was modest by compari- son-039 million. It has been pointed out that the pension funds alone invested in ordinary shares are virtually the equivalent of the total new issues of equities, which last year were unusually low at £187 million. It will be seen how important to the State the investment of these insurance and pension millions has become. They accounted last year for about half the total amount of personal savings (estimated in the White Paper at £1,993 million before depreciation, stock appreciation and tax reserves) and for nearly half the total investment in the private sector outside housing (estimated in the White Paper at £2,062 million). A Labour Government would hardly be content to leave the direction of these vast funds to the sole investment discretion of self-perpetuating boards of private directors.

In passing I would direct attention to a re- markable article in the Economist of July 25 on 'What Shape for Insurance Boards?' It argues that because insurance produces a comparatively smaller pool of trained talent from which to choose top management than most businesses, insurance companies have to adopt an unusually large number of outsiders on their boards, whose composition at first glance, it says, 'exceeds popular fantasy.' Apparently there are seventy- seven titled men among the 176 directors of our ten largest insurance companies. Among them are 'a duke, three earls, eleven viscounts, seven- teen barons, ten baronets, thirty knights and five honourables. And included in this field of the cloth of gold are three field-marshals, a general and nine Privy Councillors as well as an assorted rag-bag of pensioned courtiers, diplomats, poll- ticians• and civil servants.' It adds: 'Their "broad experience of men and affairs,” so piously intoned in the official literature, is almost uni- versally conceded as useless on an insurance board.' The awful thing is that by virtue of the directorial system these gilded but 'useless' direc- tors are self-perpetuating in office.

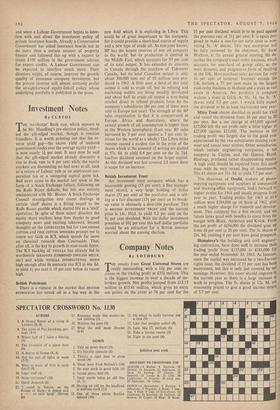

As for the investment policy of these dis- tinguished amateurs, this is usually determined by a few expert actuary-managers who swing about from gilt-edged to equities and from equities to gilt-edged according to their relative prices. From 1953 to 1961 there was a big move- ment into equities on the well-founded grounds that this class of security had been unduly de- pressed by the Labour regime of 1945-51. The success of this policy led to quite an equity cult. In 1953 the total amount of insurance funds invested in equity shares (£478.6 million) was only 121 per cent of the total. By 1961 it was £1,621 million or 22.2 per cent of the total. There v,as a slowing-down of equity investment in 1962, when share prices fell sharply, but there was a slight increase (to £1,909 million) in 1963 when it was again 22.2 per cent of the total. Successful investment in equities brings enorm- ous capital appreciation and this has encouraged the life offices to declare increasingly large bonuses on their with-profit policies. Many com- panies now draw upon their equity portfolio's capital profits solely to support bigger bonuses.

This cut-throat competition in bonuses must sooner or later have an end. When it dies down the whole question of life assurance investment is bound to be called in question. The 'with- profits' policy may be found to be too dependent on the investment whims of non-professional directors. Besides, the policy-holder is, in effect, at the mercy of the actuary who decides how much to distribute out of the confusing jumble of the balance-sheet. The public, I feel sure, will before long insist on a straightforward equity- linked policy through the medium of an inde- pendent unit trust or a separate unit trust man- aged by the insurance company. Schemes are now being advertised whereby a man or man and wife can buy a fixed-term endowment policy allowing a little over 90 per cent of the premiums to be invested in a unit trust equity portfolio (the balance going to expenses and life cover) and with the guarantee that if the husband dies suddenly his wife will get the equity units so far purchased plus cash equal to the total of the unpaid premiums. Because he obtains tax relief equivalent to £15f on every £100 paid as premium the investor in the unit trust-life schemes is in effect buying £90 or more of equity units at a discount of 51 per cent to 6 per cent. Who would prefer the unknown investments of an amateur insurance board to the certain port- folio of an equity fund which is offered at a discount on the market price and is managed by professional investment experts?

This question will be increasingly asked if

and when a Labour Government begins to inter- fere. with and direct the investment policy of private insurance boards. Already a Conservative Government has asked insurance boards not to do more than a certain amount of property finance and followed this up with a request to invest £100 million in the government scheme for export credits. A Labour Government can be expected to interfere much more. Their directors might, of course, improve the growth quality of insurance company investment, but the private investor will almost certainly prefer the straightforward equity-linked policy whose underlying portfolio is published in the press.

Previous page

Previous page