DEFENDING ONE'S OWN CASTLE

Gavin Stamp finds

his neighbours ignoring listed building laws

THE price of conservation is eternal vigi- lance, at least to judge by my painful experience over the past year which I now recount as an object lesson to anyone who may live in a listed building. It is a story worth telling as it is often assumed that the statutory listing of a building as of architectural or historical interest protects it from gratuitous mutilation.

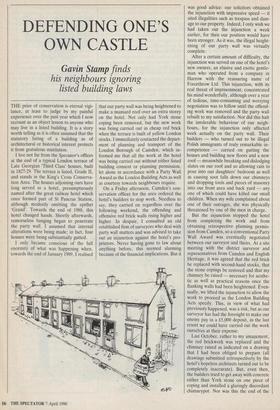

I live not far from the Spectator's offices at the end of a typical London terrace of Late Georgian 'Third Class' houses, built in 1827-29. The terrace is listed, Grade II, and stands in the King's Cross Conserva- tion Area. The houses adjoining ours have long served as a hotel, presumptuously named after the great railway hotel which once formed part of St Pancras Station, although modestly omitting the epithet 'Grand'. Towards the end of 1988, this hotel changed hands. Shortly afterwards, remorseless banging began to penetrate the party wall. I assumed that internal alterations were being made; in fact, four houses were being substantially gutted.

I only became conscious of the full enormity of what was happening when, towards the end of January 1989, I realised that our party wall was being heightened to make a mansard roof over an extra storey on the hotel. Not only had York stone coping been removed, but the new work was being carried out in cheap red brick when the terrace is built of yellow London stocks. I immediately contacted the depart- ment of planning and transport of the London Borough of Camden, which in- formed me that all the work at the hotel was being carried out without either listed building consent or planning permission, let alone in accordance with a Party Wall Award as the London Building Acts as well as courtesy towards neighbours require.

On a Friday afternoon, Camden's con- servation officer for the area ordered the hotel's builders to stop work. Needless to say, they carried on regardless over the following weekend, the offending and offensive red brick walls rising higher and higher. In despair, I consulted an old established firm of surveyors who deal with party wall matters and was advised to take out an injunction against the hotel's pro- prietors. Never having gone to law about anything before, this seemed alarming because of the financial implications. But it was good advice: our solicitors obtained the injunction with impressive speed — it sited illegalities such as trespass and dam- age to our property. Indeed, I only wish we had taken out the injunction a week earlier, for then our position would have been stronger. As it was, the illegal height- ening of our party wall was virtually complete.

After a certain amount of difficulty, the injunction was served on one of the hotel's new owners, an elusive and exotic gentle- man who operated from a company in Harrow with the reassuring name of Forcethrow Ltd. This injunction, with its real threat of imprisonment, concentrated his mind wonderfully, although over a year of tedious, time-consuming and worrying negotiation was to follow until the offend- ing work was removed and the party wall rebuilt to my satisfaction. Nor did this halt the intolerable behaviour of our neigh- bours, for the injunction only affected work actually on the party wall. Their builders — who turned out to be illegal Polish immigrants of truly remarkable in- competence — carried on gutting the houses and building new floors and a new roof — meanwhile breaking and dislodging slates on our roof and so allowing rain to pour into our daughters' bedroom as well as causing soot falls down our chimneys and dropping tools and pieces of masonry into our front area and back yard — any one of which could have killed our small children. When my wife complained about one of their outrages, she was physically threatened by one of the men in charge.

But the injunction stopped the hotel from completing the work and from obtaining retrospective planning permis- sion from Camden, so a conventional Party Wall Award was eventually negotiated between our surveyor and theirs. At a site meeting with the district surveyor and representatives from Camden and English Heritage, it was agreed that the red brick be replaced with second-hand stocks, that the stone copings be restored and that my chimney be raised — necessary for aesthe- tic as well as practical reasons once the flanking walls had been heightened. Even- tually, we lifted the injunction to allow the work to proceed as the London Building Acts specify. This, in view of what had previously happened, was a risk, but as our surveyor has had the foresight to make our enemy pay in a £5,000 deposit, in the last resort we could have carried out the work ourselves at their expense.

Last October, rather to my amazement, the red brickwork was replaced and the chimney raised as indicated on a drawing that I had been obliged to prepare (all drawings submitted retrospectively by the hotel's hopeless architects turned out to be completely inaccurate). But, even then, the builders tried to get away with concrete rather than York stone on one piece of coping and installed a glaringly discordant chimneypot. Nor was this the end of the saga, for they also managed to block the hopper at the top of our back downpipe with a piece of the red brick so that, in the torrential rain shortly before Christmas, the back wall of the house became soaked, ruining the wallpapers inside. What are, I pray, final negotiations are now proceed- ing between our two surveyors about com- pensation for our damaged roof and spoilt decorations.

Upsetting as all this has been, we have undoubtedly been lucky. As an architectu- ral historian, I knew where to go for advice and which strings to pull. Furthermore, my brother-in-law happens to be a solicitor whose firm has a specialist in planning matters. Not only did this partner defend our interests admirably but he also man- aged to extract both all costs and limited damages from the hotel — which, I gather, is a rare achievement. Fortunately, this risk of financial loss in protecting one's own interests is avoided under the Party Wall Award, for the old-established and comprehensive London Building Acts spe- cify that a surveyor's costs are to be paid by those carrying out any alterations. If our surveyor now also succeeds in obtaining satisfactory damages, I should not be much out of pocket at the end of the day. But, having gone to the trouble and expense of restoring our house as accurately as possi- ble, this is scarcely sufficient compensation for having had our work spoiled and having to endure the daily pain of the present appearance of what were once decent houses identical to ours.

What is depressing and disturbing is that had I not been around, my neighbours would undoubtedly have got away with it, for Camden Council seems not to notice most of the visual outrages that occur even just a few streets away from the Town Hall in the Euston Road. I certainly have no complaint with the council's conservation officer, whom I knew and who put up with my constant badgering and acted valiantly in my defence once I had told him what was happening. But he was constantly inhibited by his employer's policy of refus- ing to go to law and of trying to make the best of a bad job by persuasion. But my greatest complaint is with En- glish Heritage. Otherwise known as the Historic Buildings and Monuments Com- mission and set up by Michael Heseltine, this is the national statutory advisory body on historic buildings matters. Yet the only help it gave me in my battle to preserve a little piece of the nation's heritage was entirely negative. That is, the officer I spoke to on the telephone was so pessimis- tic about the possibility of ever getting illegal building work demolished that he succeeded in strengthening my resolve to take out an injunction. English Heritage is right to concentrate on important cases like No. 1 Poultry and Clause 19 of the King's Cross Railway Bill, but this should not be at the expense of the ordinary buildings of London. For, in preserving an authentic and interesting urban fabric, small details matter as much as the large and the humble as well as the special. That, after all, is why we have conservation areas — in one of which my embattled listed terraced house stands.

Things were once better managed. The old Historic Buildings Division of the Greater London Council was assiduous in protecting the authentic appearance of historic buildings and was able to call on the officers of the Planning Department. Yet the GLC's successor, the London Division of English Heritage, employs no enforcement officers although new man- agement and public relations posts have been created in the last few years. To be efficacious, all laws require both general public approval and the existence of the power to police. It seems to me that the desirability of conservation and, therefore, of the necessity for historic buildings leg- islation is generally accepted in this coun- try, but while there are people around prepared to mutilate fine buildings for commercial purposes, enforcement officers are essential. By neglecting to employ such officers to enforce the law over listed buildings and to back up feeble or spineless local planning authorities, English Herit- age is betraying our heritage and the historic fabric of London, as well as people like me.

'Okay, so where's the friendly bastard who lent me 31/2 times my annual income to buy a house?'

Previous page

Previous page