Liverpool's worst enemy

Gavin Stamp

Liverpool Tn a 'revolutionary situation', fine archi- tecture is of crucial importance. How dull those pictures of 1917 would be if the bodies and running figures were not set against the superb backdrop of Tsarist St Petersburg. How very favoured, then, is Liverpool. When the histories are written, the elegant ancien regime Town Hall will appear in the photographs of the great demonstration of 29 March 1984, which will mark — if the organisers are correct the beginning of the end of authoritarian Thatcherism. How thoughtful of the mer- chant princes of the city to have provided a building with a first floor portico and balcony, so allowing mob orators to harangue the crowd gathered in Castle Street.

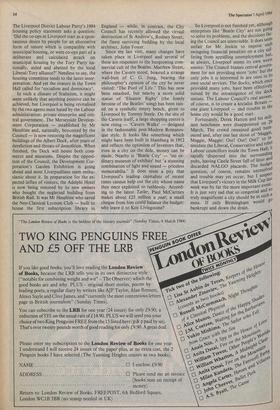

The building in which last week's acrimonious debate on the Labour ruling group's 'illegal' budget took place was begun in 1749 by John Wood of Bath and later enlarged by Wyatt. Its magnificent in- terior was the pride of Liverpudlians: as was the ancient office of Mayor until it was abolished by the Labour administration two years ago. So highly does Ken Liv- ingstone's GLC regard the building (how he would like a well-sited balcony to harangue us Londoners!) that it is prepared to buy it for ten million pounds and lease it back to Liverpool, when the Heritage Fund only had to pay eight million pounds for Belton. In earlier centuries architects knew how to combine function with civic grandeur. If Liverpool's Labour Council of the 1960s had had its way and built the planned monstrous new Civic Centre, the prelude to revolution would not look half so pictures- que.

It was an impressive sight: red flags flying above the crowd, visored cavalry waiting in the wings in case of trouble and, above the heads of the double line of helmeted policemen, speaker after speaker told us it was 'the most magnificent demonstration in the whole history of Merseyside' (the region, or the Metropolitan Council?).

'Why, this is nothing but a witch hunt!' Earlier, the demonstrators had filed Past the Corinthian colonnades of St George s Hall, past classical banks and all the visible, manifestations of Liverpool's former mercantile power and pride, waving ban- ners and chanting traditional Merseyside songs, which have words like 'Who do we hate? Tories!' and 'Maggie, Maggie, Mat gie: Out! Out! Out!' Here was the irony. Speaker after speaker condemned 'totalitarian' Thatcher for making off with 'stolen goods' which belonged to the working class which had built Liverpool, but it was capitalism which made Liverpool great: capitalism that developed the docks from which the wealth once fldwed, capitalism that produced the banks standing around the demonstrators, capitalism that needed the fine Georgian houses that Toxteth rioters delight in incin- erating, capitalism that paid for the stupen- dous cathedral. Capitalism, as such, has not failed, but Liverpool has. It is true that the move of the Cunarders to SouthamPOn was a catastrophic blow, but the liners would have disappeared anyway; it is true that, from the 1920s onwards, the middle classes deserted the city and lived elsewhere, or went south, leaving behind a working class much too dependent upon paternalist rule. But that paternalism has continued under successive Labour councils and, t° a very great extent, it is socialism that has ruined Liverpool. The Council is proposing an Mee] budget because it needs money to deal with Liverpool's appalling problems, and among the worst of the problems is housing. But the sub-standard housing is not in Victorian slums: it is in Georgian houses which the Council — the biggest landowners — are, allowing to rot and, above all, it consists or high-rise blocks of the 1960s, many 9.f which are now virtually uninhabitable. It was a Labour Council which, in the 1905' bulldozed more old houses than any other city in England and commissioned Messrs Shankland & Cox to replan Liverpool, destroying yet more buildings for projected motorways. For the unemployed of 18, of course, these catastrophes of socialist Planning belong to an earlier generation, but few lessons seem to have been learned. One ?I the most encouraging developments in housing in recent years has been the Liver- pool housing co-operatives, an attemPt to,. give tenants some control over the design or their homes and to resist the authori- tarianism of both architects and the hous- ing departments. But freedom of choice does not appeal to the Militant left which now dominates the city, and which has done its best to sabotage the co-OP projects.

The Liverpool District Labour Party's 1984 housing policy statement asks a question: `Did the co-ops in Liverpool start as a spon- taneous desire by people for an alternative form of tenure which is compatible with municipal housing, or were co-ops part of a deliberate and calculated attack on municipal housing by the Tory Party na- tionally, aided and abetted by the local Liberal/Tory alliance?' Needless to say, the housing committee tends to the latter inter- pretation. And yet the orators in the Town Hall called for 'socialism and democracy'.

In such a climate of Stalinism, it might seem unlikely that anything positive can be achieved, but Liverpool is being revitalised by the two agents most hated by the Labour administration: private enterprise and cen- tral government. The Merseyside Develop- ment Corporation — established by Mr Heseltine and, naturally, boycotted by the Council — is now restoring the magnificent buildings of the Albert Dock, after years of dereliction and threats of demolition. When finished, the Dock will house both com- merce and museums. Despite the opposi- tion of the Council, the Development Cor- poration's Garden Exhibition is going ahead and most Liverpudlians seem enthu- siastic about it. In preparation for the ex- pected influx of visitors, the Ade1phi Hotel is now being restored by its new owners who bought the neglected building from British Rail. It was Mr Heseltine who saved the Neo-Classical Lyceum Club — built to house the first subscription library in England — while, in contrast, the City Council has recently allowed the virtual destruction of St Andrew's, Rodney Street, the finest surviving building by the local architect, John Foster.

Since my last visit, many changes have taken place in Liverpool and several of these are responses to the burgeoning com- mercial cult of the Beatles. Matthew Street, where the Cavern stood, boasted a strange wall-bust of C. G. Jung, bearing the philosopher's opinion of the city he never visited: The Pool of Life.' This has now been smashed, but nearby a more solid statue of 'Eleanor Rigby' (the lonely heroine of the Beatles' song) has been rais- ed on a symbolic empty bench, given to Liverpool by Tommy Steele. On the site of the Cavern itself, a large shopping centre is now rising — 'Cavern Walks' — designed in the fashionable post-Modern Romanes- que style. It looks like something which might have been built in Hamburg in 1912 and reflects the optimism of investors that, even in a city on the dole, money can be made. Nearby is 'Beatle City' — 'no or- dinary museum of exhibits' but 'a stunning combination of light and sound — priceless memorabilia.' It does seem a pity that Liverpool's leading capitalists of recent times cannot help out the city whose name they once exploited so ruthlessly. Accord- ing to the latest Tatter, Paul McCartney makes about £25 million a year; a small cheque from him could balance the budget: why leave it to Ken Livingstone? So Liverpool is not finished yet, although enterprises like 'Beatle City' are not going to solve its problems, and the decisions fac- ing the Council are unenviable. It does seem unfair for Mr Jenkin to impose such swingeing financial penalties on a city suf- fering from appalling unemployment but, as always, Liverpool seems its own worst enemy. The Council blames central govern- ment for not providing more 'jobs' but the only jobs it is interested in are ones in its own social services. The docks, which once provided many jobs, have been effectivelY ruined by the intransigence of the dock unions. The Labour Council's real answer, of course, is to create a socialist Britain — one giant Liverpool — and trouble in the home city would be a good start. Fortunately, Derek Hatton and his mili- tant henchmen were disappointed on 29 March. The crowd remained good hum- oured and, after one last shout of 'Maggie' Maggie, Maggie: Out! Out! Out!' to in- timidate the Liberal, Conservative and rebel Labour councillors inside the Town Hall, it rapidly 'dispersed into the surrounding pubs, leaving Castle Street full of litter and discarded NALGO placards. The budget question, of course, remains unresolved and trouble may yet occur, but I suspect that Liverpool's victory in the Milk Cup last week was by far the more important event. It is just very sad that so congenial and so truly magnificent a city should be in such 3 mess. If only Birmingham would g° bankrupt and down the drain.

Previous page

Previous page