UKRAINIAN POWDERKEG

Russian experiments in Ukraine have destroyed a nation and a culture

reports Anne Applebaum WHEN the Chernobyl nuclear reactor first began to overheat, it was because a few engineers were experimenting, quite nor- mally, with the control levers. Very quick- ly, things got out of hand. Very quickly. In only four seconds the reactor reached a temperature one hundred times higher than normal. Then it exploded.

In Kiev, the capital of Ukraine, they should know about the dangers of ex- perimenting with control levers, because Kiev lies downstream from Chernobyl on the Dnieper river. The memory of Cher- nobyl floats in the city's air like an invisible radiation cloud, but now, in Kiev, there is a whole new experiment going on. This experiment has several names: perestroika, glasnost, the Shatalin Plan, 'Reform in 500 days', Ukrainian independence. This week, it took the form of an all-Ukrainian pro-independence strike. Moscow started it, allowing Ukrainian communists to back a hollow declaration of sovereignty, but Moscow doesn't seem to have realised quite how dangerous Ukraine has become politically, how difficult to reform econo- mically, how easily it will explode.

Or, more precisely, Moscow doesn't realise quite how dangerous and difficult they — the Russians — have made it. It took 350 years of Czarist domination, several decades of Stalinist purges, two collectivisation-induced mass famines, two world wars, and the refusal to teach Ukrainian children how to speak Ukrai- nian, along with the systematic elimination of anyone who might be thought a leader, an intellectual, a capitalist, or even a wealthy peasant. But they did it. The Russians have managed to rob 53 million people of their culture, to impoverish an economy which supplies one-third of the Soviet Union's food and one-fifth of its industrial products, and in effect to destroy the largest nation in the world without its own state. They aren't apologising, they aren't going to take the blame for whatever new civil war or famine or nuclear disaster results from the latest games. Even Alex- ander Solzhenitsyn, in his first essay to be printed in the motherland since he was expelled from the Soviet Union, writes that Kiev Ukraine does not exist at all: 'Ukraine is a product of Mongol invasions and Polish colonialism.'

The Ukrainian economy, which shares its problems with the rest of the Soviet Union, is only the most recent casualty. At a motorcycle factory in Kiev, the Director for Socialist Development sits up straight in his chair and explains how well he fulfilled last year's central plan, how up-to- date are his motorcycles, how good things look for the future. What he doesn't say is that the central planning system has ceased to exist, his motorcycles are outdated copies of the German wartime BMW (complete with sidecar) and about 800 of them are sitting on his shop floor, incom- plete. Parts are not arriving from Lening- rad, from Kazakhstan, from Poland, from Sweden. The Soviet Republics, afraid of shortages, no longer ship anything outside their own jurisdiction, Comecon trade has ceased to exist, no Western firm wants to trade with Ukraine, knowing it will be months before it sees any money, channel- led via Moscow. 'We are not interested in a joint venture,' says the Director for Social- ist Development. 'We are so successful, we do not need joint ventures.'

In Kiev, national pride takes many other unusual forms. At an open meeting of Rukh, the Ukrainian independence move- ment, the speaker reads out a list of demands: close the remaining Chernobyl reactors, bring in a free market economy, establish Ukrainian currency and Ukrai- nian banks, establish sovereignty over Ukrainian borders and . . . take charge of the Ukraine's nuclear weapons. 'So why shouldn't we control them?'

Behind the speaker's podium lurks a Lenin effigy of obscene height. Midway through the speeches a troop of makeshift cossacks marches across its pedestal. The cossacks seem to be wearing theatrical costumes from a production of Arabian Nights: no self-respecting, sabre-carrying, 19th-century Ukrainian cossack would have worn pink harem trousers. The crowd cheers anyway. In the countryside, things ground to a halt long ago. Looking for relief from the irradiated city, I show my driver a place on the map with a pretty name: Baleya Tserkev, 'White Church', She shakes her head. 'It is not nice village. No more white church.' I say! want nice, old and nice. She nods vigorously.

We arrive in Obuxov. The driver waves her arm across the flat central square. 'Old and nice,' she says. An empty grocery store, a town hall with boards over the windows, and another unidentifiable build- ing, probably the party headquarters, make up the square. All of the buildings are rectangular, flat-roofed, without de- coration or windows, built of the same whitish-grey brick, probably from ' the 1930s. The driver waves her arm at another Lenin, this time lifting his arm above the square, deserted at mid-day. 'Old and nice,' she says. . . Just a short walk from Obuxov there is a collective farm. The path is paved with cobblestones, and lined with linden trees. The remains of an estate? From one of the grimy outbuildings, a peasant appears, ears of corn protruding from the apron she holds up over her chest. 'What was here before this kolkhoz?' She is blank-faced, incredulous.

'Another kolkhoz. There has always been a kolkhoz here.'

'And before the Revolution?'

'Always a kolkhoz.' She smiles curious- ly. Memory reaches back no further.

In the fields, piles of hay are rotting in the autumn sunlight. No one has collected them because the combine has broken down and there are no parts to fix it. Nearby, the skeletons of ten vast green- houses stretch over acres of weed. There is no glass to fill in the skeletons, and the greenhouse generators are going to rust.

No, I explain to the driver, returning to the car, I want a real Ukrainian village.

Wooden churches. Peasant cottages. Women in flowered headscarves. 'Yes, yes,' she nods, know just where to find that.' We visit a skansen, near Kiev. A skansen is a special park, a place where 'ancient Ukrainian culture' has been preserved for the enjoyment of the urban proletariat. Exhibits of charming native architecture — wooden churches, peasant cottages — are lined neatly in rows. They have been uprooted from places like Obuxov, and reassembled here. Samples of Ukrainian 'Folk Art' — mass-produced wooden spoons and crudely painted matrushka dolls — are for sale at exorbitant dollar prices, despite the notable absence of dollar-carrying Western tourists. Elaborate signs describe the geographical and socio- economic origins of the peasants who once lived in this style of hut or that version of thatched cottage. In one of the churches, there is even a real service. A renegade sect of the Ukrainian autocephalous Orthodox Church, fed up with the intimacy between Orthodox patriarchs and com- munism, has decided to meet here. It is the closest thing they can find to authenticity. Children run back and forth outside, shouting to be given ice cream. There is a television equivalent to the skansen. At a hotel restaurant in Kiev, I watch a balalaika concert, brought to the airwaves courtesy of the Ukrainian Minis- try of Culture. Fat factory workers in synthetic flowered skirts play baleful tunes, all the time affecting the 'cultured' facial expressions of an opera singer. The bar- man curls his lip at the low-grade prosti- tutes and wants 14 dollars for a beer. If Solzhenitsyn is correct — if the Ukraine is no longer a nation — it means that the Russians who invented this system have no right to call themselves a state, or at least not a European one.

On the surface, things seem better in the western Ukraine, the strip of land which the Red Army took over from Poland in 1939 and never gave back. Like the Baltic States, the western Ukraine has suffered only 50 years of Soviet communism instead of 70. There is something left here, an occasional graceful curve to the road, the odd onion dome on a village church. Opposition has a different flavour too, both more radical and at the same time more realistic. And the last round of local elections was democratic, whereas Kiev lies under the shadow of the Communist Party, as well as Chernobyl.

In the city of Lvov — once half-Polish and half-Jewish, now all-Ukrainian — the new town council has already removed Lenin from the central square, expressly against the wishes of the Parliament in Kiev. Five days later, crowds of nervous onlookers still stand clustered around the empty pedestal, as if waiting for something to happen. The pedestal itself, the wreck- ers have discovered, was made from gravestones taken from a Jewish cemetery, destroyed by the Nazis.

'The statue was blocking the view,' explains Ivan Hel gleefully, deputy mayor of Lvov, a member of Runkh, another Ukrainian who spent 18 years in prison camp. The Lvov town council is now planning to take down all the city's Lenin statues — Lenin sitting, standing, walking, speaking, reading — put them in a park, and make their own skansen. Money earned from gate fees will be used to build flats. In Lvov, there are 850,000 people on the waiting list for flats.

In case this doesn't work, the town council has another plan: develop trade links with the West. That is, barter Ukrai- nian eggs for Polish bricks. So far the Poles are cool towards the idea. The Ukrainians want two eggs to one brick, the Poles want three. Meanwhile, in a chemists' shop in central Lvov, a sullen sales lady rings up an order on an ancient cash register marked 'National Cash Registers, Inc, made in Dayton, Ohio'. Once upon a time, Lvov was part of the big, capitalist world.

At the turn of the century, American petroleum companies even drilled for oil south of Lvov, creating a small boom in the town of Drohobycz nearby. Bruno Schulz, a Polish-Jewish writer shot by the Nazis in 1942, also lived in Drohobycz. Schulz was not kind to his home town. He once wrote that he had discovered its dark secret: 'Nothing ever succeeds there, nothing can ever reach a definite conclusion. Gestures hang in the air, movements are premature- ly exhausted and cannot overcome a cer- tain inertia . .

Failure still hangs over the town's dusty streets. Schultz's house is marked with a plaque. A woman walks out of the front door, and says she has never read his books, they aren't translated into Ukrai- nian. But at the old Polish Catholic Church, a small man — born in Dro hobycz, expelled after the war, now resi- dent in Poznan — shouts in Polish that he knows another secret about Drohobycz. Babbling inconclusively about soldiers and 1939 and blood running into his garden, he leads us round and about the city until we arrive at the back of the old Austrian courthouse.

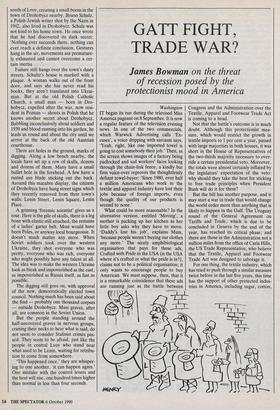

There are holes in the ground, marks of digging. Along a low bench nearby, the locals have set up a row of skulls, dozens and dozens of them. Many have a small bullet hole in the forehead. A few have a rusted axe blade sticking out the back. Around this macabre display, the citizens of Drohobycz have hung street signs which they recently removed from their town's walls: Lenin Street, Lenin Square, Lenin Place.

A grinning 'forensic scientist' gives us a tour. Here is the pile of skulls, there is a leg bone with elastic still attached, the remains of a ladies' garter belt. Most would have been Poles, or anyway local bourgeoisie. It doesn't much matter any more. When Soviet soldiers took over the western Ukraine, they shot everyone who was pretty, everyone who was rich, everyone who might possibly have any talent at all. The idea was to make the western Ukraine look as bleak and impoverished as the east, as impoverished as Russia itself, as fast as possible.

The digging still goes on, with approval of the new, democratically elected town council. Nothing much has been said about the find — probably one thousand corpses — outside Drohobycz. Mass graves, after all, are common in the Soviet Union.

But the people standing around the half-uncovered graves in nervous groups, craning their necks to hear what is said, do not seem to consider Stalinist crimes pas- sed. They seem to be afraid, just like the people in central Lvov who stand near what used to be Lenin, waiting for retribu- tion to come from somewhere.

'This happened once,' they are whisper- ing to one another, 'it can happen again.' One mistake with the control levers and the heat will rise, one hundred times higher than normal in less than four seconds.

Previous page

Previous page