Garden show

Ursula Buchan

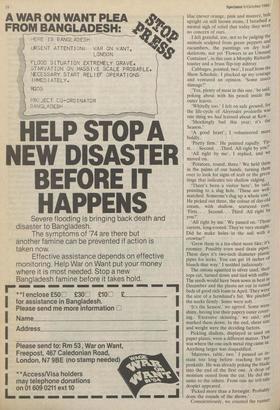

What's it going to do today?' I asked my fellow judge, as we shook hands, rough palm rasping against rough palm.

'The barograph has been steady since yesterday,' he replied. 'Hot this afternoon, I should think.' He was the head gardener on a large estate, open to visitors, which ran to rain gauges and barographs. I felt in my pockets for penknife, soft tape mea- sure, one-inch-diameter metal ring, and copy of The Horticultural Show Handbook 1981. Our province was the vegetables.

The Handbook, the bible for exhibitors and judges, is not only comprehensive technically but also adopts a forthright and high moral tone. For the competitor out for easy glory in a category where there is little or no opposition there is a section headed 'Prizes not Everything'. To those inclined to blame others for their own horticultural shortcomings, it urges, under

the title 'Be a Sportsman', that: 'An exhibitor who has failed to get a prize and cannot at once see why, should search calmly and patiently for the cause of his competitors' success so that he, himself, may be successful another time.' Should this advice fall on deaf ears, there is a section entitled 'Protests'. It was not our job, however, to award points for the Corinthian spirit.

Inside the grey canvas tent, already hot and airless and filled with the smell of jam tarts and late summer roses, other judges leaned over the central tables, cutting open scones, peering at crochet doilies and sniffing purposefully at bottles of marrow rum. Against the tent walls stood trestles of vegetables, fruit, flower arrangements and thin-waisted vases of spiky dahlias: 'Anemone-flowered', 'Collerette', 'Cac- tus', 'Semi-Cactus' and 'Pompon', their improbable flowers of flame, carmine and lilac (never orange, pink and mauve), bolt upright on still brown stems. I breathed a mental sigh of relief that today they were no concern of ours.

I felt grateful, too, not to be judging the animals sculpted from green peppers and cucumbers, the paintings on dry leaf skeletons, nor yet 'Flowers in an Unusual Container', in this case a Morphy Richards toaster and a brass flip-top ashtray. Cabbages, pointed, two', I read from the Show Schedule. I plucked up my courage and ventured an opinion. 'Some insect damage?' 'Yes, plenty of meat in this one,' he said, poking about with his pencil inside the outer leaves.

`Whitefly too.' I felt on safe ground, for the life-cycle of Aleyrodes proletella was one thing we had learned about at Kew. 'Shockingly bad this year; it's the Season.'

'A good heart', I volunteered more boldly. 'Pretty firm.' He pointed rapidly. fir," St. . . Second. . .Third. All right by you?

'All right by me', I replied, and we moved on.

'Potatoes, round, three.' We held them in the palms of our hands, turning them over to look for signs of scab or the green tinge that indicates too shallow ridging.. 'There's been a visitor here', he said, pointing to a slug hole. 'These are well; matched. Someone's dug up a whole row. He picked out three, the colour of day-old cream, with shallow, scattered eyes. 'First. . . Second. . . Third. All right by you?'

'All right by me.' We passed on. 'Three carrots, long-rooted. They're very straight. Did he make holes in the soil with a crowbar?'

'Grew them in a tea-chest more like; it roomier. Possibly even used drain pipes. These days it's two-inch diameter plastic pipes for leeks. You can get 18 inches of blanch that way.' I nodded judiciously.

The onions squatted in silver sand, their tops cut, turned down and tied with raffia. The seeds would have been sown in heat in December and the plants set out in raised beds of good rich loam in April. They were the size of a farmhand's fist. We pinched the necks firmly. Some were soft.

'It's the Season,' we agreed. Some were shiny, having lost their papery outer cover- ing. 'Excessive skinning.' we said, and marked them down. In the end, sheer size and weight were the deciding factors. Pickling shallots, displayed in sand on paper plates, were a different matter. That was where the one-inch metal ring came in. Anything larger was disqualified. 'Marrows, table, two.' I paused an in- stant too long before reaching for mY penknife. He was already poking the blade into the end of the first one. A drop of moisture oozed from the cut. He did the same to the others. From one no tell-tale droplet appeared.

'Picked more than a fortnight. ProbablY done the rounds of the shows.'

Conscientiously, we counted the runner beans, 30 gooseberries, and, the judge's nightmare, 36 brussels sprouts. The tomatoes, too, were casualties of the nightmare, 36 Brussels sprouts. The tomatoes too, were casualties of the Season. Many were soft, and some none too fresh, judging by the way the calyces curled in.

Finally, we came to rest in front of the Collections. 'Eight varieties, to be display- ed in a box measuring not more than 33 inches by 20 inches.' The tape measures Were unwound again. There was no doubt who had won: huge, scrubbed parsnips lay on black velvet, flanked by ruler-straight runner beans and glossy tomatoes; every strand of leek-root had been cleaned and

straightened. We were in the presence of a master. But we went through the motions. 'Maximum points, dwarf French beans 15, cabbages 15, leeks 20, lettuces 15 'First. . . Second. . . Third. All right by you?'

'All right by me'.

We parted amicably, pleased to have done the task without disagreement and in the time allowed, for, as usual, the entries were down on last year: no surprise when so many allotments are neglected or ploughed for cereals.

`Will you be at the — Show next week?' he inquired.

'Yes', I replied. 'It's the Season.'

Previous page

Previous page