The topless towers of Manhattan

Peter J. M. Wayne

RISE OF THE NEW YORK SKYSCRAPER, 1865-1913 by Sarah Bradford Landau and Carl W. Condit Yale, £50, pp. 478 ELEGANT NEW YORK: THE BUILDERS AND THEIR BUILDINGS, 1885-1915 by John Tauranac and Christopher Little Abbeville, £49, pp. 286

And especially does the New Yorker delight in the whimsical, the inconsistent, the unexpected. He is like a child who likes to dig in the sand with a silver spoon, and to eat porridge with a toy shovel.

Joyce Kilmer 1916

These two beautiful volumes attempt to analyse the architectural fruits of such capricious predilections from the middle of the 19th century to the outbreak of the first world war. Although the authors concen- trate their not inconsiderable energies on the same city during the same era, each looks at their subject through very different eyes.

Rise of the New York Skyscraper is the architectural historians' architectural histo- ry. It deals (down to the last rivet) with the technological minutiae of construction; the evolution of the iron frame; windbracing; geological considerations (the rock base- ment of New York); fireproofing; heating; lighting; ventilation; plumbing ....

Sarah Bradford Landau tackles the foun- dations of the 700-foot Metropolitan Life Tower sunk by pneumatic caissons to bedrock of depths varying from minus 28 foot to minus 46 foot, the concrete piers under the footings transmitted at . 50,000 lbs per square foot or pronounces on the Tribune Building of 1875, whose floor arches were moulded to fit as voussoirs between beams that were uniformly 12.75 inches deep with spans that varied from 10 foot 4 inches to 14 foot 2 inches.

If you enjoy precision of this exactitude, then the Landau/Condit volume is the one for you. Thankfully, the text is relieved with a superb collection of photographs of the many now demolished masterpieces, vast commercial maisons de Wile that seem to have been picked at whim from the boule- vards of Haussmann's Paris, and trans- planted lock, stock and balcony to the gridlocked streets of Manhattan.

Tauranac's book is another story, concerned more with the social niceties of living within these buildings than with their architectural history. Crashing snob that he is, he chronicles the apportionment of Fifth Avenue with the same evident relish as Landau measures the girths of myriad wrought iron girders.

Here displayed in all their metropolitan glory are the Whitneys, the Goulds, the Rockefellers, the Carnegies, the Warburgs and of course the ubiquitous Astors and Vanderbilts. At one stage in the 1880s, the Vs occupied no less than seven properties between 51st and 58th Streets, ranging from William H. Vanderbilt's Italian renaissance 'Doge's Palace', to William K. Vanderbilt's moated neo-Loire château, and Cornelius Vanderbilt II's extravagant residence where the oak beams were inlaid with mother of pearl. In 1896, Caroline Schermerhorn Astor (the Mrs Astor) opened her Fifth Avenue mansion with a

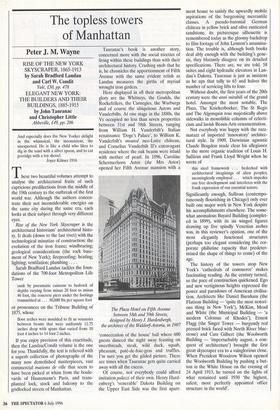

The Plaza Hotel on Fifth Avenue between 58th and 59th Streets, designed by Henry.l. Hardenbergh, the architect of the Waldotf-Astoria, in 1907 'consecration of the house' ball where 600 guests danced the night away feasting on sweetbreads, steak, wild duck, squab, pheasant, pate-de-foie-gras and truffles. I'm sure you get the gilded picture. There are times when Tauranac gets quite carried away with all the excess.

Of course, not everybody could afford imitation palazzi of their own. Henry Hard- enberg's 'venerable' Dakota Building on the Upper East Side was the first apart- ment house to satisfy the upwardly mobile aspirations of the burgeoning mercantile classes. A pseudo-baronial German château in yellow brick and olive rusticated sandstone, its picturesque silhouette is remembered today as the gloomy backdrop to film footage of John Lennon's assassina- tion. The trouble is, although both books deal ably enough with the building's gene- sis, they blatantly disagree on its detailed specifications. There are, we are told, 58 suites and eight hydraulic elevators in Lan- dau's Dakota. Tauranac is just as insistent as he ups that tally to 65. and halves the number of servicing lifts to four.

Without doubt, the first years of the 20th century were the anni mirabili of the grand hotel. Amongst the most notable, The Plaza, The Knickerbocker, The St Regis and The Algonquin rose majestically above sidewalks in monolithic columns of eclecti- cism and lavish Beaux-Arts ornamentation.

Not everybody was happy with the razz- matazz of imported 'innovatory' architec- tural style. In 1909, Darwinian agnostic Claude Bragdon made clear his allegiance to the more organic tradition of Louis H. Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright when he wrote of this steel framework ... bedecked with architectural imaginings of alien peoples, meaninglessly employed ... which impedes our free development and interferes with the frank expression of our essential nature.

Significantly enough, Sullivan (contempo- raneously flourishing in Chicago) only ever built one major work in New York despite his accomplishments elsewhere. The some- what anomalous Bayard Building (complet- ed in 1899), with its six winged figures drawing up five spindly Venetian arches was, in this reviewer's opinion, one of the most elegantly functional structures (perhaps too elegant considering the cor- porate philistine rapacity that predeter- mined the shape of things to come) of the age.

The history of the towers atop New York's `cathedrals of commerce' makes fascinating reading. As the century turned, so the pace of construction quickened. Ego and new vertiginous heights expressed the power and paradoxes of American civilisa- tion. Architects like Daniel Burnham (the Flatiron Building — 'quite the most notori- ous thing in New York'), McKim, Mead and White (the Municipal Building — 'a modern Colossus of Rhodes'), Ernest Flagg (the Singer Tower — burgundy red pressed brick faced with North River blue- stone) and Cass Gilbert (the Woolworth Building — `imperturbably august, a con- quest of architecture') brought the first great skyscraper era to a vainglorious close. When President Woodrow Wilson opened the Woolworth Building by pushing a but- ton in the White House on the evening of 24 April 1913, he turned on the lights of what remained until 1930 'the highest, safest, most perfectly appointed office structure in the world'.

Previous page

Previous page