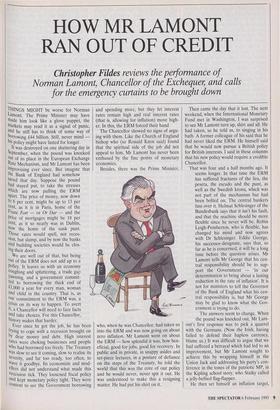

HOW MR LAMONT RAN OUT OF CREDIT

Christopher Fildes reviews the performance of

Norman Lamont, Chancellor of the Exchequer, and calls for the emergency curtains to be brought down

THINGS MIGHT be worse for Norman Lamont. The Prime Minister may have made him look like a glove puppet, the markets may read it as a signal of panic, and he still has to think of some way of borrowing £44 billion. Still, never mind his policy might have lasted for longer.

It was destroyed on one shattering day in September, when the pound was knocked out of its place in the European Exchange Rate Mechanism, and Mr Lamont has been improvising ever since. But imagine that the Bank of England had somehow saved that day. Suppose the pound had stayed put, to take the stresses which are now pulling the ERM apart. The price of money, now down to 6 per cent, might be up to 13 per cent, as it is in Paris, home of the Franc Fort — or Or Dur — and the Price of mortgages might be 18 per cent, as it so nearly was in Dublin, Those the home of the sunk punt.

nose rates would spell, not reces- sion, but slump, and by now the banks and building societies would be clos- ing their doors.

We are well out of that, but being out of the ERM does not add up to a Policy. It leaves us with an economy Coughing and spluttering, a trade gap Yawning, and a government commit- ted to borrowing the thick end of £1,000 a year for every man, woman and child in the country. That is, as our commitment to the ERM was, a crisis on its way to happen. To avert it, a Chancellor will need to face facts and take choices. For this Chancellor, history makes that harder.

Ever since he got the job, he has been

by to cope with a recession brought on oy dear money and debt. High interest rates were choking businesses and people who had borrowed too freely. The Treasury was slow to see it coming, slow to realise its severity, and far too ready, too often, to wave it goodbye. Its economists and mod- ellers did not understand what made this recession tick. They loosened fiscal policy and kept monetary policy tight. They were content to see the Government borrowing

and spending more, but they let interest rates remain high and real interest rates (that is, allowing for inflation) move high- er. In this, the ERM forced their hand.

The Chancellor showed no signs of argu- ing with them. Like the Church of England bishop who (so Ronald Knox said) found that the spiritual side of the job did not appeal to him, Mr Lamont has never been enthused by the fine points of monetary economics.

Besides, there was the Prime Minister, who, when he was Chancellor, had taken us into the ERM and was now going on about zero inflation. Mr Lamont went on about the ERM — how splendid it was, how ben- eficial, good for jobs, good for recovery. In public and in private, in snappy asides and set-piece lectures, in a posture of defiance on the steps of the Treasury, he told the world that this was the core of our policy and he would never, never spit it out. He was understood to make this a resigning matter. He had put his shirt on it. Then came the day that it lost. The next weekend, when the International Monetary Fund met in Washington, I was surprised to see Mr Lamont turn up, shirt and all. He had taken, so he told us, to singing in his bath. A former colleague of his said that he had never liked the ERM. He himself said that he would now pursue a British policy for British interests. I said in these columns that his new policy would require a credible Chancellor.

That was four and a half months ago. It seems longer. In that time the ERM has suffered fractures of the lira, the peseta, the escudo and the punt, as well as the Swedish krona, which was not part of the mechanism but had been bolted on. The central bankers fuss over it. Helmut Schlesinger of the Bundesbank says that it isn't his fault, and that the machine should be more flexible since he never will be. Robin Leigh-Pemberton, who is flexible, has changed his mind and now agrees with Dr Schlesinger. Eddie George, his successor-designate, says that, so far as he is concerned, it will be a long time before the question arises. Mr Lamont tells Mr George that his cen- tral responsibility should be to sup- port the Government — 'in our determination to bring about a lasting reduction in the rate of inflation'. It is not for ministers to tell the Governor of the Bank of England what his cen- tral responsibility is, but Mr George may be glad to know what the Gov- ernment is trying to do.

The answers seem to change. When the pound was knocked out, Mr Lam- ont's first response was to pick a quarrel with the Germans. (Now the Irish, having failed to defend their hapless currency, blame us.) It was difficult to argue that we had suffered a betrayal which had led to an improvement, but Mr Lamont sought to achieve this by wrapping himself in the Union Jack and addressing his party's con- ference in the tones of the patriotic MP, in the Kipling school story, who Stalky called a jelly-bellied flag-flapper.

He then set himself an inflation target, complete with a whole range of indicators, so that he could judge whether he was like- ly to hit it. This was a worthy attempt to replace, from domestic resources and in a less mechanical form, the discipline that we had been importing through the ERM. It meant that he and his advisers would have to decide which indicators to believe, and when — and policy-makers so placed are always apt to believe the voice that tells them what they want to hear. They scarcely had a chance to choose before they acquired a new purpose, and found them- selves committed to a strategy for growth.

What strategy? One part was, evidently, cheaper money. Bank base rates were led down from 10 per cent (their floor in the ERM) to 7 per cent, with the usual stern hint that this was now enough. The Chan- cellor and his colleagues then tried to write growth into his autumn statement. This was a strange affair. It refused to pick and choose between plans to spend public money on public projects, since all would be good for the infrastructure and for the contractors, like builders of hospitals or nuclear submarines.

The cuts, so described, would be lower increases in public sector pay. Experience does not suggest that the lid on that saucepan can be held down and kept down, or that ministers will not press for their own special cases — but even on its face value, the arithmetic of the statement was shocking. It showed that the Chancellor, who had budgeted to borrow an unprece- dented £28 billion in this financial year, would now need £37 billion, and that next year would be worse. He must in cold blood plan to borrow £44 billion.

That was enough policy-making for one year. Christmas brought a late flurry in the shops, January brought the bill, in the fig- ures for imports. The banks, routinely faulted for not lending enough, complained that their customers kept bringing money back. Unemployment carried on upwards. The Chancellor's seven new economic advisers, who could not be expected to agree on whether it was raining, agreed that interest rates were still too high. Time for the next swing of policy.

Down with a clang, last week, came bank base rates, by a full 1 per cent, to 6 per cent — their lowest since the 1970s. That was clearly a signal, even if the signal was not clear. The markets are used to the idea that interest rates go up sharply and come down slowly, a little at a time. Even a cut of 1/2 per cent now would have been part of a normal progression, leaving the markets looking forward to the other half as a chas- er with the Budget. This, though, was something else. Did it make 5 per cent the next stop? Would sterling be left to take the consequences? If it was meant as a kick-start for the economy, would the Gov- ernment go on kicking like this until it started?

The Treasury put out a notice, to say that this cut was entirely consistent with the tar-

gets it had set itself. The Prime Minister's office put out a notice, to say that he and the Chancellor and the Bank of England had all agreed on what to do, in perfect harmony. The markets were unconvinced, and so was sterling. They thought it far more likely that bad economic news most of all, unemployment — had rattled the Government into accepting that some- thing new was needed, and that the initia- tive had come, as well it might, from the Prime Minister.

That was not much help to a Chancellor six weeks away from his Budget. It is not as though Budget day will be a jolly occasion. How could it be, with a £44 billion deficit looming ahead? If he wanted to bring his Budget into balance he would have to dou- ble income tax. As things are, the word from the Government leaking machine is that the Prime Minister thinks this no time to go around raising taxes — the recovery, even if we have one, is too frail to stand it. December, with the first of the new-style budgets, would be soon enough to start cutting the deficit down to size. In March, Mr Lamont would have so little scope that he might just as well call the whole thing off and let everyone go to the Cheltenham races.

This, though, is not an evil day that can be put off indefinitely, and the longer it is left, the more evil it is likely to be. It is part of the bill for the ruinous strategy which made our monetary policy too tight and our fiscal policy too loose, in the dim hope that these two mistakes would cancel one another out. They did not. They both had to be corrected. Correcting monetary poli- cy was the easy part — cutting interest rates, letting the exchange rate fall — and we are well on with that. Correcting fiscal policy — cutting spending, raising taxes is the hard part, and has still to be faced.

We could, and on present form will try to, rub along like that, giving ourselves all the pleasure of bringing policy back towards balance but none of the pain. Short of distributing the nation's gold reserves at street corners, there is not much more that a government eager to stimulate recovery could do. That route, though, ends up in a cul-de-sac, or one of two, and To think I dodged the draft by pretending to be gay . .

with bad luck we could reach both. It leads towards trouble with the balance of pay- ments and with the financial markets where the Chancellor must raise his money. As part of Britain's contribution to the single European market, we are doing away with the trade figures. This, if not helpful, looks tactful. At their farewell appearance a fortnight ago, they showed that our bal- ance of payments on current account was in deficit to the tune of £1 billion a month at a time of deep recession, which ought to be a good time for the balance of pay- ments, if for nothing else. Heaven knows how far the trade gap will widen if, as the Chancellor with half his heart wishes, con- sumers' confidence returns, and we all stream back to the shops with our credit cards, to stock up on imports.

That in turn would make life harder for him as a borrower. There is nothing like balance-of-payments trouble for scaring the wits out of holders of sterling, and British Government stock. To borrow money on this scale a Chancellor will have do more than say please. The markets will set terms to him — borrowers cannot be choosers. Even on terms, they cannot expect to see their debt bubble on upwards, inexorably swollen by compound interest, which can be so much stronger than the debtor's will or power to repay. Lenders know that. The time comes, as Mr Lamont could tell us, when a borrower runs up against his credit limit.

There is a way out of these dead ends, and it is signposted Export. By mistake, in a public defeat for British policy, and at a direct cost estimated at £4 billion, that way was opened to us on 16 September, when the markets devalued the pound. When he opens his Budget on 16 March, Mr Lamont will have his chance to say, as he would have done better to say six months earlier, that the policy of Her Majesty's Govern- ment is to make devaluation work.

That means a once-for-all shift of resources towards our export markets. It does not mean, and would not be consis- tent with, spending at home — restored consumer confidence, more money in the shops — or with borrowing and spending by the Government, which is not an exporter and never will be. It would mean facing the unpleasant choices which, in the autumn statement, were ducked. It must mean a tight fiscal policy to go with the loosening of monetary policy that devalua- tion represents. Without that, the opportu- nity will run away into the sands of inflation, as it can too easily and has too often.

By now it is rather late for the present Chancellor to say such things, and in prac- tical terms, too late. These are policies for a bruiser, able to punch his weight in the Treasury and out of it, a Chancellor in the mould of Denis Healey or of Nigel Lawson. They are policies of austerity, which was Stafford Cripps's watchword, but CriPPs was by nature austere. They are in contra- diction to the policy that this Chancellor pursued for two years and might be pursu- ing now if the markets had let him. It is evident now (and was evident then) that the fracture of that policy was the time for a clean break. Mr Lamont, having put his credibility on the line for it, should have left the Treasury, as did Jim Callaghan in similar circumstances 25 years earlier — and it did him no harm, in the end. The Treasury, though, is a political power-base, as John Major has reason to know, and he was not going to turf out a natural ally to make room for a possible rival. The unhap- py consequence is that he and we have had to manage with a devalued Chancellor. That has been no service to anyone, and least of all a service to Norman Lamont.

Previous page

Previous page