ARTS

Exhibitions

Essential Australia

Giles Auty

Fred Williams: Paintings of the Pilbara (Serpentine Gallery, till 24 February) Looking back on the Sixties and Seven- ties, I remember thinking how inappropri- ate it was, at the time, that valuable travelling scholarships were awarded so regularly to slavish devotees of the latest, usually cerebral, international fashions. What earthly difference would it make to be in Rome, New York or New Delhi if one's eyes were resolutely closed, as an artist, to the surrounding scenic stimuli? I have already told the tale of the Minimalist who covered over the windows of his studio, which looked over one of the loveliest bays in this country, lest the perceived world distract him.

For my money, the artist who claims he is tired of the rolling green ocean, or the rolling green hills, is generally not just tired but tiresome. The optical wonders and complexities of our natural world can not only lift the spirit but also humble it. Artists who have tried, for any length of time, to come to terms with the seen, know the experience as baffling, frustrating and humiliating yet, in the long run, irreplace- ably beneficial.

The more purely cerebral or self- referential art becomes, the more gloomily introspective or arbitrary its likely nature. The impulses for Gauguin's sorties to the Marquesas, or those of Fred Williams to a remote, northwesterly corner of Australia, must mystify those brought up to believe that formal or colour relationships are the whole business of art. Such unfortunates can but surmise it is better to blunder on in some south London 'art-space', soaking up the habitual moonshine of modern art magazines, than to undergo a potentially changing and enriching experience of land- scape and culture under a foreign sun.

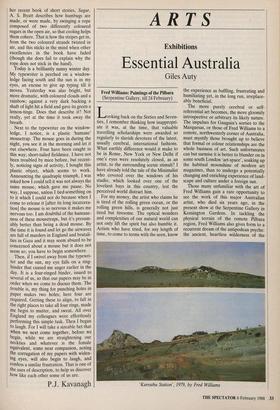

Those many unfamiliar with the art of Fred Williams gain a rare opportunity to see the work of this major Australian artist, who died six years ago, in the present show at the Serpentine Gallery in Kensington Gardens. In tackling the physical terrain of the remote Pilbara region, Fred Williams also gives form to a recurrent dream of the antipodean psyche: the ancient, heartless wilderness of the `Karratha Station', 1979, by Fred Williams Australian heartland, that inland 'outback' which many a Sydney or other coast-city surburbanite has never set eyes upon, but which is always remorselessly present in the back of their minds.

Other, archetypal Australian painters, notably Russell Drysdale and Sydney Nolan, have stamped their visions on this unforgiving interior, in similar manner perhaps to the way Constable and Gains- borough have affected our national con- sciousness of English landscape. However, in the rather shorter life-span of Australian artistic tradition, the problem of escaping from an imposed vision may have seemed to Williams weightier and more urgent.

Many modern painters try to achieve a desired originality intellectually, by creat- ing studiously constructed, art-historical niches for themselves. Naturally these niches are fabricated with a watchful eye on contemporary criticism. By now such contrived contexts have become an all too familiar part of Western artistic culture, yet their validity seems impossible to jus- tify. I suggest that only those artists who follow their innermost, idiosyncratic im- pulses are worthy of the description 'ori- ginal'. Williams's own freshness of vision grew as he abandoned himself increasingly to the experience of the outback. It is the transmission of a basically human no less than an aesthetic response which warms us to his art.

One test of an artist's success in getting to grips with the spirit of a region is the degree of desire the resultant work evokes in the viewer to go and see for himself. Williams's paintings make clear that it is outcrops and ridges of iron ore, deep gorges and harsh desert which give the Pilbara its remorseless grandeur. Williams flew over the area a number of times and worked directly from nature at ground level. He also digested and often general- ised his experiences, seeking pictorial dis- tillations.

This London exhibition makes an in- teresting contrast, as a whole, with that based on Ayer's Rock, shown in June 1986 by Williams's near contemporary, the En- glish artist Michael Andrews. The latter's images, whether of rock masses or vegeta- tion, were more directly descriptive. Wil- liams favours a more modernist, abbrevi- ated shorthand wherein dots and dabs of paint may be read as generally descriptive of scrubland, yet exist also, in their own right, as elements of an almost spaceless abstract composition.

The artist's colour is often beautiful and expressive but I could not help wondering, while looking at the exhibition, what the genius of Turner might have made of this strange, timeless landscape. The modernist simplifications of Williams's method are sometimes, but not always, an advantage. On occasions, the brashness of the artist's approach seems almost studied. Perhaps this is an inescapable part of the experience thus far, at least, of being an Australian.

Previous page

Previous page