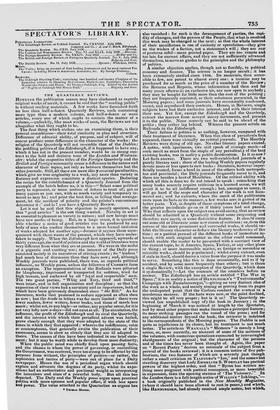

THE QUARTERLY REVIEWS.

HOWEVER the publication season may have slackened as regards original works of merit, it cannot be said that the " reading public" is without reading. materials. A few weeks have furnished forth no less than halt-a-dozen Quarterly Reviews, each containing more type than a modern volume, and half-a-dozen or more articles, every one of which ought to contain the matter of a volume,—unluckily, like most works of man, the Reviews are not altogether what they ought to be.

The first thing which strikes one on examining them, is their

general resemblance—their total similarity in plan and structure. Difference of editorial ability, of purpose, and of subject, will of course produce some difference in the character of the works: the religion of the Quarterly will not resemble that of the Dublin; the peddling politics of the Edinburgh, if it happened to have any, which it has not in the present number, would be in strong con- trast to the bold and decisive tone of the London and Westmin- ster; whilst the respective titles of the Foreign Quarterly and the British and Foreign necessarily cause a difference in the nature and character of their topics, not only as between themselves but the other journals. Still, all these are mere idio yacratical peculiarities, which give no true originality to a work, any more than variety in features and expression constitute a distinct species. Deducing the recipe for the establislummt of a Quarterly Journal from the example of the batch before us, it is this—" Select some political party to represent, or some section of letters to treat of; get as many papers as you can, with as much variety and temporary in- terest as may be; and print the best first, or failing that arrange- ment, let the accident of priority and the printer's convenience determine it :" and lo ! you have a Quarterly Review.

Let it not be said that this objection is merely specious, and that "good articles" is the tont thing wanted. Novelty in art is as essential to pleasure as variety in nature; and new beings must have new modes of being. But, in a large sense, it is question- able whether a series of good articles can be produced by any body of men who confine themselves to a mere formal imitation of works adapted for another age,—because it argues them unac- quainted with those wants of the present, which they have under- taken to supply. When the Edinburgh first appeared, upwards of thirty years ago, the world of polities and the world of literature were very different from what they are at present. We were in the midst of a gigantic and exciting war; the interest of the Daily press consisted mainly in its narratives of stirring events ; its " leaders " Lad much less of discussion than they have now ; and, although Weekly journals were published, there was, as regards political influence, no Weekly press, unless the followers of CORBETT form an exception. The representatives of the Radicals were pilloried for blasphemy, imprisoned or transported for sedition, tried for high treason, and eschewed by all "loyal and respectable' men. The two great parties, "Whig and Tory, thief and thief,"* were intact, and in full organization and discipline ; so that the exposition of their views had a certainty and an importance, both of which have been grievously diminished since "the Bill." As for literature, works that promised to endure appeared as often then as now ; but the trade in letters was far more limited : there were fewer readers, fewer writers, fewer books, and those of much less merit ; whilst art, in any high—or rather, any popular sense, for it is Dot very lofty now-a-days—did not exist at all. The circulation, the influence, the profit of the Edinburgh and its rival the Quarterly, and the interest with which their periodical advent was hailed, prove clearly enough that they were adapted to the state of the times in which they first appeared ; whereas the indifference, calm or contemptuous, that generally awaits the publication of their successors, seems to show as clearly that they are ill adapted to theirs. The causes of this have been indicated in our brief state- ment; but it may be worth while to develop them more distinctly. When the public mind was chiefly fixed upon passing facts, and the classes in whom the power of governing, or controlling the Government, was centered, were too strong to be affected by the pressure from without, the principles of politics—or rather, the sophistries and tactics of party—were out of place for a Daily newspaper. Hence the use of a periodical organ which should explain and advocate the dogmas of its party, whilst its expo- sitions had an authoritative and positional weight as interpreting the intentions and aims of a powerful body. But all this has departed. The Daily and the Weekly press argue upon practical politics with more aptness and popular effect, if with less space and power. The value attached to the Quarterlies as organs has

• Timms' Mooax.

also vanished : for such is the derangement of parties, the rapi- dity of changes, and the powers of the -People, that what is resolvect

this week may be changed in the next; so that the whole interest

of their manifestoes is one of curiosity or speculation—they give us the wishes of a faction, not a statesman's will ; they are car et preterea nihil—mere printed paper. They are too remote and too late for current affairs, and they are not sufficiently advanced themselves, to serve as guides to the principles and the philosophy of politics. A similar objection applies, though not so forcibly, to political economy and finance. The science is no longer occult ; it has

been extensively studied since 1806. Its materials, then acces- sible to few, are patent to almost every one: a treatise may be purchased for as much as the price of a number of the Review; the Returns and Reports, whose information had then and for many years aftewai tls an exclusive air, are now open to anybody ; they may be bought for little more than the cost of the printing ; they are frequently reprinted, or their substance presented, in the Morning papers ; and some journals have occasionally condensed, recast, and reproduced their contents. Hence, in Reviews, single

subjects have lost their exclusive interest, and with their interest their use. Yet few, except the Edinburgh and the Quarterly,. extract the marrow from several massy documents, and present it to the public. None scarcely can be said to be ahead of the public ; they rather lag behind. Witness the present article on. Railroads in the Edinburgh. Their failure in politics is as nothing, however, compared with their treatment of literature. When this class of periodicals first appeared, there were virtually no critical journals. The Monthly Reviews were dying of old age. No other literary papers existed. A notice, with specimens, (we still speak of average merit—of such merit as must form the staple of any periodical,) of the best existing books, was in reality a public desideratum. Is it so now ? Let facts answer. There are two well-established journals of a purely literary cast ; three of the leading Weekly papers regularly devote more or less space to new books : literature, however super- ficially treated, forms a head in most of the others both metropoli- tan and provincial; the Daily journals frequently recur to it, and there are besides a host of Monthlies. Of the critical ability with which all this is done we do not intend to speak : remarking that many books scarcely require criticism in a learned sense, we will. grant it to be all indifferent enough ; but, amongst so many, it will go hard if the scope and character of the work is not ham- mered out ; and for extracts, where the merit of the publication. rests upon its facts or its manner, a few weeks sees it gutted of its better parts. Yet, in despite of these symptoms of a total change, the greater periodicals go on as if thirty years had not passed. Who that reflects upon the subject can avoid seeing. that no review should be admitted in a Quarterly without some surpassing and therefore rare merit, or sonic distinctive feature. It should carry out some old or illustrate some new canon of criticism ; or, from the nature of the more prominent and successful works, it should ex- hibit the literary character or deduce the literary tendencies of the time ; or a patient perusal of the different books of immediate in- terest, with such original matter as the editor could command, should enable the reader to be presented with a succinct view of the current topic, be it America, Spain, Turkey, or any other place or thing ; or more inaccessible matter, as foreign or recondite or scientific works, should be popularized ; whilst every extract, even if stale in itself, should derive a value from the purpose it was made to serve. Something like this is done occasionally, and as if by accident, and by some more frequently than others ; but is there a single Review, with the exception of the Quarterly, which does it systematically?—Let the contents of the numbers before us answer. The Edinburgh has an article entitled "The War in Spain ;" it is in reality a notice of IIENNINGSEN'S "Twelvemonths' Campaign with Zumalacarregui,"—giving no very distinct idea of the work as a whole, and merely aiming at proving from its pages the undisputed point that the Carlists conduct the contest in a murderous manner. If the facts were new, or the point doubted, this might be all very proper ; but is it so? The Quarterly re- viewed (an unpublished copy of) the book in January ; in the beginning of March it was noticed at length by the Spectator, and by most other papers that make literature a principal feature; its more striking passages ran the round of the press ; and for any additional matter beyond the book, the reviewer is indebted to the correspondents of the Morning papers. The Dublin is not quite so injudicious in its choice, but its treatment is not much better. The article on WRAXALL'S " Memoirs" is merely a long notice, or, more correctly, an abstract of some of the sections of the volumes, with numerous quotations connected by intermingled abridgments of the original ; but the character of the persons and of the times has never been thought of. Again, the paper on " Recent Poetry" derives no rationale of the subject from a perusal of the books reviewed; it is a common notice of five pub- lications, the two features of which are a severely just though rather a small criticism on TALFOURD'S "Ion," and the somewhat startling discovery that Lady EMMELINE S. WORTLEY has poetical powers of the highest order, and that " Byron has written no- thing more pregnant with poetical conception, or more beautiful in expression, than the opening stanzas of 'The Visionary.— In the London there is a full-length notice of Wtstis's " a book originally published in the New Monthly Magazine, (where it should have been allowed to rest in peace,) and which, like HENNINGSEN, had already received ample notice, but which, even had its contents been less stale, possessed neither intrinsic merit nor adventitious interest to challenge notice in a Quarterly journal. The subject of COURTENAY'S " Memoirs of Temple," in the British and Foreign, is more adapted to its place; but, with the exception of a notice of the Bishop of Munster, there is nothing in the at ticlo beyond the book, or differing from what has already been said of it.

Although the numbers before us have furnished the opportu- nity for these temarks, they have not been the sole occasion of them, nor are they intended to have so limited an application. Neither have we attempted to point out the model of a new Quarterly; nor to determine whether sufficient ability exists in the country to sustain six reviews, or, if existent, is likely to be available at the terms they can afford to offer; nor shall we dis- cuss the most important point of all, whether the Miscellaneous Quarterlies have not outlived their uses and their times ?—We pass to a cursory notice of the numbers before us.

Previous page

Previous page