BOOKS

All done with mirrors

Bevis Hillier

ON REFLECTION by Jonathan Miller National Gallery Publications, £25, pp. 224 Let's get one thing straight, right away. In Noblesse Oblige, Nancy Mitford suggest- ed that 'mirror' was non-U and that the U expression was `looking-glass'. Presumably, Snow White's stepmother was not only wicked but common as muck, because she did not say: Looking-glass, looking-glass on the wall, Who is the fairest of us all?

As far as I am concerned, the last word on the subject was a comment by that merry fellow, the late Sir kin Moncreiffe of that Ilk. He told me he had written to Nancy Mitford:

An ancestor of mine was known as 'The Mirror of Chivalry'. Do I now have to call him 'The Looking-Glass of Chivalry'?

In this review I shall use 'mirror' through- out — and to hell with it if, as a result, I'm not invited to Queen Charlotte's Ball.

The title of Dr Miller's book is nicely ambiguous, but his subject is mirrors in art — in the broadest sense of 'reflective sur- faces', including still water, shining armour and a metal coffee-pot. The book accom- panies an exhibition which opens at the National Gallery on 16 September, Mirror Image: Jonathan Miller on Reflection. It happens that the gallery owns the two most famous paintings in the world containing mirrors — Van Eyck's The Anzolfini Por- trait, and Velazquez's The Toilet of Venus, known as 'the Rokeby Venus'. This latter is the work that a suffragette slashed in 1914 in protest at the treatment of women as what would now be called 'sex objects'. In the 1970s, when Lucio Fontana was creat- ing his razor-slashed blank canvases and Vanessa Redgrave was a leading feminist, I had a vision of Redgrave rushing into the Tate Gallery with a box of oil-paints to vandalise a Fontana by painting a Rokeby Venus over the razor slash.

We all know critics whose idea of art is a canvas scarred with a razor, a sawn-up, pickled sheep or a block of ice melting in a shed, drip by drip. Such fascinating con- cepts. These people favour the smear-word `illusionistic' for representational art. Thus Leonardo is reduced to the conjuror at a children's party: the poor mutt (they imply) Just couldn't muster the imagination to do more than paint what he saw, by ignoble trickery. By taking the mirror in art as his theme, Miller presents us with an illusion within an illusion, like the play within a play in Hamlet. (Ophelia, by the way, deftly solved the Nancy Mitford predicament when she described Hamlet as 'the glass of fashion and the mould of form'.) In both a painting and a mirror, three dimensions are reduced to two — a neat trick.

Here, then, is a subject of a complexity to tax even Miller's infinitely subtle mind. Private Eye, in the days when Peter Cook felt he needed to have a dig at his old Beyond the Fringe comrade, used to portray `Dr Jonathan' as a self-important would-be Renaissance Man; but, in truth, Miller is as near to an uomo universale as you could find today. Any study of mirrors brings in science as well as art, and he is versed in both. At the very time he was capering about the stage in Beyond the Fringe, in the early Sixties, the egregious C.P. Snow was Gerald Brockhurst, Adolescence (detail), 1932, etching on paper. British Museum deploring, in Encounter, the chasm that had opened between 'the two cultures', art and science (drawing a poisoned reply from F.R. Leavis — that is to say, a reply from F.R. Leavis). Miller is the answer to the Maiden's Prayer. He has a doctorate in medicine; produces operas; makes television series; and has written several books, including The Body in Question, about the workings of the human body. Early on, he gave him- self a nursery-slopes training in 'mirrors in art' by directing a television film about Alice's adventures, with Malcolm Mug- geridge as the Gryphon and Sir Giel- gud as the Mock Turtle. You might think, therefore, that in this long illustrated essay Miller had found his ideal subject — a test- piece in which all his varied talents could be focused in one brilliant point of light.

To a large extent, he does not disap- point. Half the battle with a book of this kind is in the choice and reproduction of the pictures. Miller's selection is wonder- fully wide-ranging and the quality of the colour is good. (That is more than can be said for the letterpress, which is greyish rather than black. I have not yet reached the stage of the oldies described in Bob Monkhouse's 70th-birthday show, 'who go to an old-people's restaurant where the alphabet soup has specially large lettering', but this murky text sent me to the Optrex bottle. I know that grey is the new black, but. . . . ) Miller has corralled mirror-inclu- sive works from all over the world, though he exasperatedly notes that some of the institutions gave 'inexplicable refusals' when asked to lend to the National Gallery show. Many of the paintings will be unfa- miliar to most readers, among them a still- life of peaches reflected in rococo silverware, painted by Alexandre-Francois Desportes about 1733-34 and Johann Erd- mann Hummel's amazing scene (1831) of a vast granite bowl being polished in a work- shop, the window-lights on its surface the only indication of its shape. The latter pic- ture is in the Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin. Gerolamo Bedoli's Portrait of Anna Eleano- ra Sanvitale (1562) is in the Galleria Nazionale, Parma. Private collections are raided too. From one of them comes a glo- rious mealy-surfaced still-life by Sir William Nicholson, The Silver Casket (1919). Besides being a masterful woodcut artist, and one half of the `Beggarstaff Brothers' team which revolutionised British poster art, Nicholson was the finest still-life painter of this century. But for the fact that what seems to be a silver tea-caddy in this work is of spare neo-classical style, one could easily think this a work by Chardin, the 18th-century master of whom it was said that he painted not with brushes and colours, but with air and light.

Reading the book is rather like being guided round an exhibition by a cicerone with a good eye and an unusually fecund and allusive mind. He points out things one might easily miss: for example, that God the Father, in a 1514 Coronation of the Vir- gin, is meant to be seated in heaven, but, absurdly, the crystal orb he is holding unmistakably reflects a mullioned window. Presumably it is a studio window of the artist, Hans Suess von Kulmbach — as in, `Kulmbach, all is forgiven.' Miller engi- neers some telling juxtapositions. On facing pages we see Bedoli's Anna Eleanora San- vitale (the young girl faces us, and the beribboned back of her head is reflected in a mirror behind her) and Magritte's La Reproduction Interdite (1937), showing Edward James looking at the brilliantined back of his own head in a mirror. This one of the more witty and delicately exe- cuted of Magritte's works — is perhaps the third most famous painting incorporating a mirror: Miller calls it 'notorious'. This is what he writes about it:

The laws of optics . . . are not exactly com- mon knowledge, and yet everyone can tell that there is something unacceptably wonky about Edward James' appearance in the mir- ror. So wonky, in fact, that we are tempted to cast around for an explanation which does not require it to be a mirror. What if the frame over the mantelpiece encloses a hole in the wall and Edward James is looking at his identical twin who happens to be facing at the same direction next door? No such luck! Magritte carefully forecloses this explanation by including a perfectly orthodox reflection of the book on the mantelpiece immediately in front of the mirror. So it is a mirror after all, and we are back where we started with the problem of how it is that this particular duplication is so glaringly unacceptable as a reflection.

That is Miller at his most relaxed and engagingly colloquial. You will not find `wonky' in the art history writings of Bernard Berenson, any more than you will find Mrs Thatcher's 'wobbly', as addressed to George Bush, in the speeches of Disraeli. But at other times Miller changes gear into the kind of scientific or sociological writing that insists on stating the blindingly obvious in roundabout or fancy language.

As well as our encounters with Miller the art historian and Miller the scientist, we are treated to Miller the philosopher. In Beyond the Fringe there was a sketch in which Miller twisted his body into ever more tortured arabesques as he posed and then attempted to answer teasing questions of semantics. Some of his questions and observations in this book could have gone straight into that sketch without changing a word.

We can try without any success to see our own hindquarters, but when it comes to see- ing what we see with, the notion of trying makes no sense whatever. In fact our own head and neck are incorrigibly invisible [with- out a reflecting surface]. How then do we succeed in recognising our own reflection when we do catch sight of it? If we don't know what we look like until we see our- selves in the mirror, how can we tell, when we do see ourselves for the first time, that the reflected face is ours?

Well, of course, it is obvious that when baby sticks his finger into his ear and his reflection sticks a finger in its ear, it begins to dawn on baby that there may be some link between himself and the dribbling apparition in front of him. There was one exception to this pattern: Narcissus, who, as Miller amusingly comments, was stupid enough to fall in love with a watery reflec- tion which he believed to be somebody else — a case of homoaquaticism, if we may mix Greek with Latin. Miller is severe on Freud for mistakenly giving the label 'nar- cissism' to self-love, but I am afraid he is forgetting what he himself wrote in the Observer on 1 October 1961. In an article headed 'Can English satire draw blood?', timed to coincide with the opening of Peter Cook's club, The Establishment, he suggest- ed that the real British establishment were threatening the satire boom with 'castration by adoption'. He had noticed how, during the run of Beyond the Fringe, 'sleek Bentleys evacuate a glittering load into the foyer'.

Some of the harsh comment in the prog- ramme is greeted with shrill cries of well bred delight which reflect a self-indulgent narcissism which takes enormous pleasure in gazing at the satiric reflection.

The passage is startlingly clairvoyant: already, 37 years ago, Miller was reflecting on reflections. As for the use of `narcissim', he could reasonably claim that Freud gave the word a meaning which he, Miller, was entitled to appropriate.

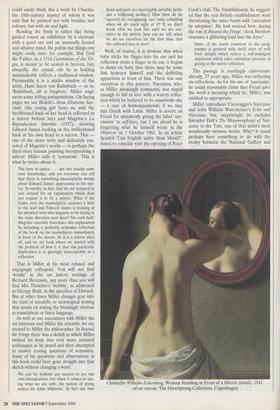

Miller reproduces Caravaggio's Narcissus and John William Waterhouse's Echo and Narcissus, but, surprisingly, he excludes Salvador Dali's The Metamorphosis of Nar- cissus in the Tate, one of that artist's most wondrously virtuoso works. Why? It could perhaps have something to do with the rivalry between the National Gallery and Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg Woman Standing in Front of a Mirror (detail), 1841, oil on canvas. The Hirschprung Collection, Copenhagen the Tate. (The National Gallery's admirable director, Neil MacGregor, tells a story about a man who vandalised a painting in the gallery. When asked why he had chosen that work, the vandal replied, 'Well, I did go into the Tate first, but I couldn't find anything worth vandalising.') But I think there is a different reason for the omission in this book not only of Dali's Narcissus, but of any mention of Dali whatever. If ever there was an artist who revelled in optical illusions and the ambiguity of reflections, it was he. But to the arts establishment today, Dali is not an okay artist. That he was a fas- cist and an inventive pervert might perhaps be overlooked. That towards the end of his life he connived at forgeries of his work by signing blank sheets of paper might even be admired: as somebody pointed out in a recent newspaper letter, it would probably have won him the Turner Prize today. No, what really bugs the arts establishment is that Dali developed a flawless painterly technique — in a word, 'illusionism'. That he put it to the service of the surreal was insufficient mitigation.

Miller is no arts apparatchik. He is far too intelligent and moral for that. He is quite prepared to cause flutters in estab- lishment dovecotes when the urge takes him, as evidenced by his recent rant about Pavarotti. But I am sure he knows that if you want to be taken seriously by the arts establishment, you do not put your chips on Dali. No, sir! I believe that a subcon- scious inhibitor may have come into play when he was deciding whom to include: it has robbed him and us of a key player.

I further believe that if Miller had been organising an exhibition of paintings of anything other than mirrors, the same acquired reflex which gave him the red light on Dali would have given him a green one on all the assorted junk of modernism — 'conceptual' art, the smudge-upon- smudge canvases of Rothko, Rachel Whiteread's inside-out sculptures, the meandering scribbles of Cy Twombley (All twombley were the borogroves. . . ). But the mirror in art has this miraculous prop- erty: it acts as a sort of antibody repelling all artistic maladies. Like the play within a play in Hamlet, it brings things to a crisis. The only way you can depict a mirror is to show it reflecting something — and that something needs to be recognisable. The mirror's incorruptible surface is a boo to all the geese. It is the prosecutor's Taccuser before which the charlatan wilts; the clear, unwinking gaze he dares not look in the eye.

Dali is the most disappointing omission, but there are other topics that one might have expected Miller, with his 'satiable curtiosity', at least to touch on, such as Leonardo's so-called 'mirror writing'; or distorting mirrors and the 18th-century Prince of Palargonia, a dwarf who filled his palace at Bagheria, Sicily, with sculptures of midgets and with distorting mirrors to cut his guests down to his own size. Miller notes that few paintings show men looking in mirrors (since men were usually doing the painting, and had the idie _fire that women are the vain sex), but misses Duncan Grant's pastiche of the `Rokeby Venus' in which a nude youth ogles his own reflection. Miller bubbles over with ideas about art and science, but seems less interested in excur- sions into literature, though the Lady of Shalott gets a look-in through having been painted by Holman Hunt. Writing on the idea of reflection as intermediary, he might have quoted Dryden's liquescent lines from `Eleanora: A Panegyrical Poem Dedicated to the late Countess of Abingdon':

But as the Sun in Water we can bear, Yet not the Sun, but his Reflection there, So let us view her here, in what she was, And take her image in this waery Glass; Yet look not ev'ry Lineament to see; Some will be cast in shades; and some will be So lamely drawn, you scarcely know, 'tis she.

Again, palindromes are an obvious liter- ary spin-off from mirrors, ranging from the `imperfect' variety, such as 'NOW STOP, MAJ- OR-GENERAL, ARE NEGRO JAM-POTS WON?'

to the 'perfect' sort in which the words themselves remain intact when read back- wards, as in 'AVID RATS GNAW ANNA WANG, STAR DIVA', or the old advertisement for an acne cream, 'STOPS SPOTS'. (There are musi- cal palindromes, also. Some have been recorded by the choir of Magdalen College, Oxford.) Clearly, too, Miller has not seen the offensive propaganda leaflet which the Nazis dropped on British troops in the sec- ond world war. It shows a pretty Aryan girl seated naked in front of a mirror and read- ing the Times, which by then had abandoned its pre-war stance of appeasement and was patriotically anti-German. From the mirror leers back a grotesque caricature, evidently intended to represent a Jewish girl, and, by some juggling with the letters 'E' and 'S', the word 'Times' is reflected as `Semit'.

I have always thought Miller clever beyond clever: a compliment, as opposed to `too clever by half. But I do wonder how many people will be queuing up to pay £25 for a book on mirrors in art. It is not a sub- ject that fits neatly into any art college syl- labus. For the person of average culture, it is wildly recherche. I suppose it might appeal to voyeurs. There are lots of luscious female nudes: with mirror-inclusive paint- ings, as with Emmanuelle-type films about lesbian lovers, you get 'two for the price of `Waiter! There's a fly on the wall in my soup!' one'. (Was Gerald Brockhurst pure in heart when he created his etching, shown here, of a pubescent girl in front of a dress- ing-table mirror? Miller is carefully non- committal, describing the image as 'a painful crisis of personal identity'.) I can imagine the less voyeuristic readers reach- ing the end of the book and wondering what was the point of the whole enterprise, many-faceted as a Come Dancing witch- ball. 'It has been like watching a man trying to unscramble an egg,' they might whinge, `awfully clever, but to what end?' They would be misguided. Miller manages to confront and address some of the most profound questions about what happens when we look at a work of art. A compell- ing salesman of his own theories, he gets at least one foot in the doors of perception.

Previous page

Previous page