Exhibitions

The Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center (Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia, USA)

Weighty implications

Giles Auty

Mindful of my deeply Eurocentric nature, I approached a recent three-week stay in Virginia with the determination to be a perfect ambassador of my country. After all, we share a common language. My resolve lasted well into the second day, when a waiter in rather a pretentious restaurant asked if I would care for my potatoes tawg rattin'. Regrettably, in an anxiety to understand, my mind flew at once to the porcine renown of the state, for Virginian ham is justly famous. During a lengthy impasse, the last thing to occur to me was that the waiter might have been trying to speak French: au gratin. My attempted diplomacy had failed miserably at the first hurdle. For much of my adult life I seem to have been trying to under- stand all things American with similar lack of success. Yet for anyone connected with the visual arts, to try remains essential, because the influence of the USA on con- temporary art during the past 40 years has been little less than colossal. Why a large list of American artists have acquired great fame remains incomprehensible to me, but I continue my quest.

Driving through Virginia on a damp day, it would be easy to imagine one was pass- ing through Surrey, with only the occasion- al butterfly of pocket handkerchief size to dispel the illusion. Once away from the Blue Ridge mountains and approaching the coast, I encountered fireflies, humming birds, pelicans and curious cicadas which whirr like band-saws — sure signs of a cli-

mate much hotter than England's in an area of land almost exactly the same. Nor- mally only five million people live in the state of Virginia, but their numbers are swollen in summer by scores of thousands of visitors. Just how they are swollen may not seem altogether appropriate to an art critic's column, but I would argue that observation of almost any kind can offer relevant insights. To understand a nation's art properly it is necessary to look further afield than the walls of its galleries.

A recent American President voiced public concern that many of his fellow countrymen were overweight. I seem to recall the figure of 20 lbs being mentioned. Today this figure would be appropriate only to American children. A remarkably high percentage even of quite young Amer- ican women I saw were 30-50 lbs in excess of anything either healthy or natural, while their menfolk were no less regularly 40-70 lbs over the odds. Beside the James river, at one of the first sites of British settlement in America, the three youngish couples preceding me up a slope were positive Titans. What would their ancestors have made of such 200 and 250 lb monsters? Ironically, Virginia is the state where the Confederacy was finally starved as well as blockaded and beaten into submission dur- ing the Civil War. When assaulting Yankee positions, the Confederate soldiers were often inspired by the thought of the rations they might seize. The Confederacy boasted wonderful cavalry, for its agile, self-reliant woodsmen and country boys made excel- lent horsemen. Yet mere horses could not begin to move under the weight of the shuddering sea elephants in shorts who were among my fellow visitors to the his- 'Deborah Glen, 1739, by an unknown artist toric Civil War sites of Bull Run, New Mar- ket and Appomattox.

If current Americans do not see or care about what is happening to their bodies, is it any likelier they can observe or act upon what is occurring to their art? I fear that along with bodily flab may have come a concomitant loss of intellectual agility. Modern art has become a subject of which most Americans stand now simply in rever- ential awe. Indeed, the nation's art critics seem to exist only to praise it in all its man- ifestations or to massage an ailing market in avant-garde artefacts. It has taken an Australian, Robert Hughes, writing for Time magazine, to take the living art of America to task. Of late, the claims made for current American artists such as Holz- er, Schnabel and Salle have been as inflat- ed as the waistlines of so many of the country's inhabitants.

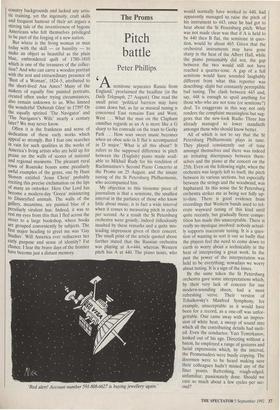

On the credit side, on a number of the wetter days of my holiday, I visited muse- ums and other centres devoted to historical record or reconstruction which were uni- formly excellent. These included the Muse- um of American Frontier Culture at Staunton, the Museum of the Confederacy at Richmond, the site of an early 17th- century settlement at Carter's Grove and the site of Robert E. Lee's historic surren- der, which concluded the Civil War, at Appomattox. Most of the historic attrac- tions of Colonial Williamsburg are set out with similar intelligence and thoroughness, none more so than the town's two major museums. I found the Dewitt Wallace Dec- orative Arts Gallery, which shows English and American furniture, textiles, prints, ceramics, glass and metals hard to praise too highly both in its displays and organisa- tion. No less interesting, not least in the provision of interesting historical insights, is the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center, which is also part of the restored and reconstructed seat of 18th-century British government at Williamsburg. I have no especial liking of folk art, yet the vast range of examples on view at the Folk Art Center reveals the growth of a vital, self-reliant and independent-minded people. Here is art full of honesty, tough- ness and humour, at the furthest possible remove from the flaccid, fashionable and self-obsessed variety which throngs so many American museums of modern art today. The men and women who created extraordinarily beautiful weather-vanes and decoys, shop-signs and quilts did not even consider themselves to be artists, yet were closer to achieving such status, in their absence of pretence, than many contempo- rary Americans who consider themselves masters of an artistic calling. Historic America holds up a looking-glass to a living nation which has tragically lost sight of itself. Present material comfort has brought complacency; by contrast, many of those who created the wonderful objects in the Folk Art Center were poor or itinerant. Indeed, many came from uneducated,

country backgrounds and lacked any artis- tic training, yet the ingenuity, craft skills and frequent humour of their art argues a stirring tale of the inventiveness of bygone Americans who felt themselves privileged to be part of the forging of a new nation.

But where is the living woman or man today with the skill — or humility — to make an object as beautiful as the plain blue, embroidered quilt of 1780-1810 which is one of the treasures of the collec- tion? And who can carve a wooden portrait with the zest and extraordinary presence of `Bust of a Woman', 1824-5, attributed to the short-lived Asa Ames? Many of the makers of equally fine painted portraits, created often under trying circumstances, also remain unknown to us. Who limned the wonderful 'Deborah Glen' in 1739? Or the equally spirited 'The Navigator' and The Navigator's Wife' nearly a century later? We may never know. Often it is the frankness and sense of dedication of these early works which appeal so strongly. But I fear one searches in vain for such qualities in the works of America's living artists who are held up for praise on the walls of scores of national and regional museums. The pleasant rural town of Roanoke boasts some peculiarly awful examples of the genre, one by Hunt Slonem entitled 'Jesus Christ' probably exciting this precise exclamation on the lips of many an onlooker. Here Our Lord has become a modern-day 'Green' ministering to Disneyfied animals. The walls of the gallery, meantime, are painted blue of a peculiarly virulent hue. Indeed, it was to rest my eyes from this that I fled across the street to a large bookshop, where books are grouped conveniently by subjects. The first major heading to greet me was 'Gay Studies'. Will America ever rediscover her early purpose and sense of identity? Fat chance. I fear the brave days of the frontier have become just a distant memory.

Previous page

Previous page