Exhibition

The Image of London: Views by Travellers and Emigres 1550-1920 (Barbican Art Gallery till 18 October)

Through others' eyes

Giles Auty

- o you ever wonder how somewhere you know well would look to you if you were seeing it for the first time? Probably the nearest one can get to this experience is to show such a place to strangers. By noticing what interests and excites them some of the pleasures can be relived second-hand. Clearly, the unfamiliar has a different effect on us from the known, not simply because of its visual freshness, but also through limitations in our knowledge of what we are viewing. In childhood an important part of the experience of land- scape depends on our ignorance. While we are still unaware what lies behind a certain high wall or woody hill, the unexplored terrain retains a vital element of mystery. In much the same way the sights, smells and sounds of other countries excite us at first, even as adults, simply by their strangeness. This is why most of us find the capitals of foreign countries more intri- guing and glamorous than our own. Con- versely, our national institutions and char- acteristics are probably as fascinating as any to outsiders. All this makes the present exhibition at the Barbican — of London seen through the eyes of travellers and emigres — especially interesting. For some odd reason, emigrees fail to feature among the 90-odd artists represented. Only a few years ago some student art-world sister- hood would surely have taken the exhibi- tion organisers to task for this presumed discriminatory insult to their collective sex. May we hope that those embarrassing times are now behind us?

During the 18th and 19th centuries London had two personalities in the eyes of foreigners: modern Rome or modern Babylon. The former description referred to the London rebuilt by Wren after the Great Fire of 1666 — an architecturally classical city that was also politically stable and culturally advanced. The Babylonian view was preferred primarily, I suspect, by nations with whom were were having territorial or religious fisticuffs. Interes- tingly, London was held up as the symbolic capital of vice and corruption not only by foreign artists such as Gustave Dore who made a deal of money from his sensationalist portrayals — but, closer to home, by Engels, who saw our capital as a prime showplace for the evils of capitalism.

London quadrupled in population in the century before the Great Fire. By the time of that catastrophe it boasted 400,000 citizens — roughly twice the size of present-day Plymouth. Much of the earlier work in the exhibition, by artists from the Low Countries, Italy, France and Switzer- land takes the form of unreliable topogra- phy. It was left to Wenceslaus Hollar, an artist of Bohemian origin rather than habits, to put our burgeoning capital into more accurate perspective with his com- prehensive view of 1647. Two small Rem- brandts from much the same period were conceived from other artists' images, as the master is unlikely ever to have visited this country. Both drawings feature old St Paul's, unusual views from a northern aspect. One of the five Canalettos on view, painted in London just over a century later, is of the new cathedral.

Canaletto wished on London the virtual- ly cloudless skies of his native Venice, and even distant buildings sparkle in the murk- free sunshine. Yet London probably had a worse climate then than today. Contem- porary paintings of winter 'frost fairs' held on the Thames show the river frozen to sufficient depth to allow daily commerce. The wealthier shoppers arrived in horse- drawn carriages which are shown charging over the ice in unstoppable fashion. In 1739 the Thames froze over above London Bridge from Christmas until February. Perhaps our contemporary climate is not as harsh as we imagine. The last time I remember the Thames freezing over was in 1963 — but this was as far up-river as Hampton Court. Similarly, the terrible smoke-laden London fogs which were still spreading misery up until the Fifties now mercifully seem behind us. Yet dense London fogs, along with the helpfulness of our Metropolitan policemen, remain part of the enduring myth of London as seen through foreign eyes.

Our capital's riverside mists and fogs were certainly essential to the paintings of Whistler and Monet, for powerful, if romanticised, evocations of the city. Oscar Wilde took both to task for laying it on a bit thick: 'Where, if not from the Impress- ionists, do we get those wonderful brown fogs that come creeping up our streets, blurring the gas lamps and changing the houses into monstrous shadows? . . . The extraordinary change that has taken place in the climate of London during the last ten years is entirely due to a particular school of Art.'

After 1920, the date when the last paintings in the exhibition were made, the idea of trying to paint the experience of living in other people's capitals, or even in one's own, fell into increasing disrepute among the sophisticates of the art world. Today foreigners seldom come to London to paint what they see. Many prefer to get involved in the latest supposedly interna- tional styles and to hide all evidence of their roots. They, and we, are the losers.

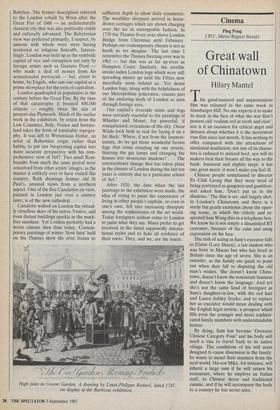

High finks in Covent Garden. A drawing by Louis-Philippe Boitard, dated 1747, on display at the Barbican exhibition.

Previous page

Previous page