Mrs Thatcher and the press

Stephen Fay

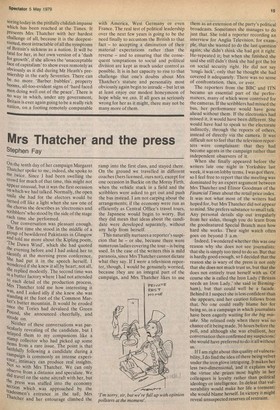

On the tenth day of her campaign Margaret Thatcher spoke to me; indeed, she spoke to me twice. Since I had been swelling the crowd for much of that time, this might not aPPear unusual, but it was the first occasion on which we had talked. Normally, the open smile she had for the electors would be turned off like a light when she saw one of the chorus she describes as 'electronics and scribblers' who stood by the side of the stage each time she performed. Our conversation was pleasant enough. The first time she stood in the middle of a group of bewildered Pakistanis in Glasgow (and told me more about the Kipling poem, The Dawn Wind', which she had quoted the evening before and I had asked her to identify at the morning press conference. She had put it in the speech herself. I Wondered if she knew it all by heart; not all, She replied modestly. The second time was in a butter factory where I had not attended to each detail of the production process. Mrs Thatcher told me how interesting it Was, and I asked idly if she knew she was standing at the foot of the Common Market's butter mountain. It would be eroded once the Tories had devalued the Green Pound, she announced cheerfully, and strode on. Neither of these conversations was particularly revealing of the candidate, but I relayed them to my companions like a s.tamP collector who had picked up some Items from a rare issue. The point is that faithfully following a candidate during a campaign is commonly an intense experience; intimacy can produce real insights. Not so with Mrs Thatcher. We can only serve from a distance and speculate. We did travel on the same aircraft with her, but the press was stuffed into the economy section which was approached by the tradesmen's entrance in the tail; Mrs Thatcher and her entourage climbed the ramp into the first class, and stayed there. On the ground we travelled in different coaches (hers licensed, ours not), except for one occasion in Buckie on the Moray Firth, when the vehicle stuck in a field and the scribblers were asked to get out and push the bus instead. I am not carping about the arrangements; if the economy were run as efficiently as Central Office's travel tours, the Japanese would begin to worry. But they did mean that ideas about the candidate were developed separately, without any help from herself.

This naturally nurtures a reporter's suspicion that he — or she, because there were numerous ladies covering the tour — is being used. In the case of the writers this is mild paranoia, since Mrs Thatcher cannot dictate what they say. If! were a television reporter, though, I would be genuinely worried, because they are an integral part of the campaign, and Mrs Thatcher likes to use them as an extension of the party's political broadcasts. Sometimes ihe manages to do just that. She told a reporter recording an interview for Anglia Television, for exam-, ple,.that she wanted to do the last question again; she didn't think she had got it right. He-repeated it; but when she finished she said she still didn't think she had got the bit on social security right. He did not say 'tough luck', only that he thought she had covered it adequately. There was no sense of confrontation, then, or ever.

The reporters from the BBC and ITN became an essential part of the performances, many of which were contrived for the cameras. If the scribblers had missed the bus, her performance would have gone ahead without them. If the electronics had missed it, it would have been different. She would have had to speak to the electorate indirectly, through the reports of others, instead of directly via the camera. It was difficult not to feel that the television reporters were complaisant: that they had become agents in the campaign rather than independent observers of it.

When she finally appeared before the writers late one night in Yorkshire last week, it was on lobby terms. I was Qot there, so I feel free to report that the meeling was dominated by an expert argument between Mrs Thatcher and Elinor Goodman of the Financial Times about the retail price index. It was not what most of the writers had hoped for, but Mrs Thatcher did not appear to mind. She prefers substance to small talk. Any personal details slip out irregularly from her aides, though you do learn from the goodnatured Special Branch men how hard she works. Their night watch often goes on beyond 3 a.m.

Indeed, I wondered whether this was one reason why she does not see journalists: that she is simply too tired to do so. But that is hardly good enough, so I decided that the reason she is wary of the press is not only that she does not much trust us, but that she does not entirely trust herself with us. Of course she is called the Iron Lady ('Britain needs an Iron Lady,' she said in Birmingham), but that could well be a facade. Behind it I suspect she is less confident than she appears, and her caution follows from that. No one could really blame her for being so, in a campaign in which journalists have been eagerly waiting for the big mistake. She relaxed only when there was no chance of it being made, 36 hours before the poll, and although she was ebullient, her conversation then confirmed my suspicions: she would have preferred to do it all without us.

If I am right about this quality of vulnerability, I do find the idea of there being velvet under the iron glove intriguing. It makes her less two-dimensional, and it explains why the virtue she prizes most highly in her colleagues is loyalty rather than political ideology or intelligence. In defeat that vulnerability would make her life a torment: she would blame herself. In victory it might reveal unsuspected reserves of restraint.

Previous page

Previous page