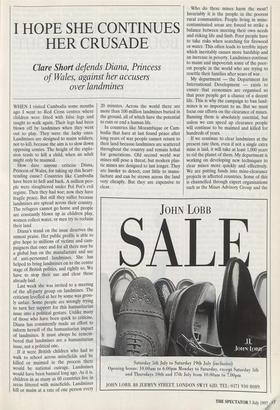

I HOPE SHE CONTINUES HER CRUSADE

Clare Short defends Diana, Princess

of Wales, against her accusers over landmines

WHEN I visited Cambodia some months ago I went to Red Cross centres where children were fitted with false legs and taught to walk again. Their legs had been blown off by landmines when they went out to play. They were the lucky ones. Landmines are designed to maim soldiers, not to kill, because the aim is to slow down opposing armies. The height of the explo- sion tends to kill a child, when an adult might only be maimed.

How dare anyone criticise Diana, Princess of Wales, for taking up this heart- rending cause? Countries like Cambodia have been to hell and back. A million peo- ple were slaughtered under Pol Pot's evil regime. Then they had war; now they have fragile peace. But still they suffer because landmines are spread across their country. The refugees cannot go home and people are constantly blown up as children play, women collect water, or men try to reclaim their land Diana's stand on the issue deserves the utmost praise. Her public profile is able to give hope to millions of victims and cam- paigners that once and for all there may be a global ban on the manufacture and use of anti-personnel landmines. She has helped to bring landmines on to the centre stage of British politics, and rightly so. We have to stop their use and clear those already laid. Last week she was invited to a meeting of the all-party group on landmines. The criticism levelled at her by some was gross- ly unfair. Some people are wrongly trying to turn her support for this humanitarian issue into a political gesture. Unlike many of those who have been quick to criticise, Diana has consistently made an effort to inform herself of the humanitarian impact of landmines. It must always be remem- bered that landmines are a humanitarian issue, not a political one. If it were British children who had to walk to school across minefields and be killed or maimed in the process there would be national outrage. Landmines would have been banned long ago. As it is, children in as many as 60 countries live in areas littered with minefields. Landmines kill ,or maim at a rate of one person every 20 minutes. Across the world there are more than 100 million landmines buried in the ground, all of which have the potential to ruin or end a human life.

In countries like Mozambique or Cam- bodia that have at last found peace after long years of war people cannot return to their land because, landmines are scattered throughout the country and remain lethal for generations. Old second world war mines still pose a threat, but modern plas- tic mines are designed to last longer. They are harder to detect, cost little to manu- facture and can be strewn across the land very cheaply. But they are expensive to clear. Who do these mines harm the most? Invariably it is the people in the poorest rural communities. People living in mine- contaminated areas are forced to strike a balance between meeting their own needs and risking life and limb. Poor people have to take risks when searching for firewood or water. This often leads to terrible injury which inevitably causes more hardship and an increase in poverty. Landmines continue to maim and impoverish some of the poor- est people in the world who are trying to resettle their families after years of war.

My department — the Department for International Development — exists to ensure that economies are organised so that poor people get a chance of a decent life. This is why the campaign to ban land- mines is so important to us. But we must focus our efforts on the clearance of mines. Banning them is absolutely essential, but unless we can speed up clearance people will continue to be maimed and killed for hundreds of years.

If we continue to clear landmines at the present rate then, even if not a single extra mine is laid, it will take at least 1,000 years to rid the planet of them. My department is working on developing new techniques to clear mines more quickly and effectively. We are putting funds into mine-clearance projects in affected countries. Some of this is channelled through expert organisations such as the Mines Advisory Group and the Halo Trust, but the most important thing we are doing is training people in mine- infested countries to clear their own mines.

The most moving thing I saw in Cambo- dia was widows and amputees engaged in the slow and painstaking process of mine clearance. I am particularly keen to ensure that the victims of landmines benefit from some of the projects we are supporting. Amputees or widows are trained in mine clearance and thus earn a living from the very instruments that blight their commu- nities. This goes a small way to breaking the cycle of poverty that landmines create.

I hope that the hostile comments of a few people will not prevent Diana from continuing her crusade against landmines. Our government has already signed up to the fastest international process towards a global ban. By December an international treaty will be in place committing signato- ries to a ban.

Diana's commitment and the hope she has been able to give have played an important part in making more countries take notice. There is still much to do because some countries like the United States have not yet signed up. Diana is to be praised, not criticised, for this brave and valuable humanitarian work.

The author is Secretary of State for Interna- tional Development.

Previous page

Previous page