THE ECONOMY & THE CITY

Advice to Mr. Callaghan

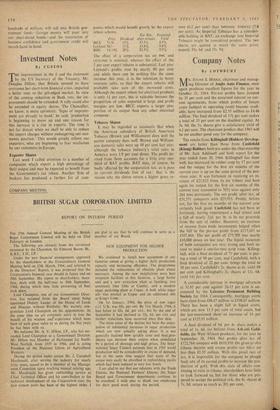

By NICHOLAS DAVENPORT rr tits article is respectfully intended to per-

suade Mr. Callaghan not to make a bloomer next April. The talk is that he feels shOrt of revenue, that the wicked Tories had committed the Government to a prodigal increase in public expenditure and were relying on a 4 per cent growth in the economy (which will no longer be realised) to provide the extra revenue, that the Estimates, even after pruning, will be much higher than last year's, and that he must there- fore raise fresh taxation, although—God help us all!—he is putting up income tax from 7s. 9d. to 8s. 3d. and introducing a corporation tax which could either soak the companies or strip the shareholders. The rumour is that he is being egged on by the Treasury establishment, which, as usual, is terrified of inflation, of over- employment, of overheated industries, of wages chasing prices and of wage-drift upsetting' the incomes policy. The danger is that Mr. Callaghan will be pushed into concocting a too deflationary budget with an excessively large surplus which will bring the expansion of the country to a halt. I want to save him from making the ghastly mistake of Mr. Selwyn Lloyd, who applied a severe deflation to an economy which was already turning down.

I would first warn him against the neurotic over-conservatism in budget-making which is endemic in the Treasury. For nine years up to Mr. Maudling's first budget, the Treasury suc- ceeded in exacting forced savings from the public at the rate or£357 million a year! That was the average annual size of the unreasonably large budget surplus. In April 1963, the Chancellor estimated a borrowing requirement which turned out to be greatly excessive, expenditure being put too high (to the extent of £158 million) and revenue too low (to the extent of £51 million). An error of £209 million is being followed by a worse error for 1964-65. Expenditure is less and revenue much more than Mr. Maudling had anticipated. Mr. Callaghan has said : 'Present in- dications are that, before allowing for the tax changes, the overall deficit (that is, the borrowing requirement) would have been £250 million less than my, predecessor's estimate.'

These mistakes are a very serious matter. The growth of the economy has long been slowed down by over-taxation. And Mr. Callaghan is being pressed to repeat the same deadly error of over-conservative finance.

Is Mr. Callaghan really scared of inflation? if so, is it a wage-cost inflation or a demand infla- tion? This year, allowing for the wage agreements negotiated at the end of 1964 (including a 9 per cent increase for railwaymen), we can expect a rise in wage rates of at least 6 per cent. But as the manufacturers and retailds are already put- ting up their prices to offset their profits squeeze before Mr. George Brown's incomes commission can influence them—it cannot stop them—we may rest assured that the increase in consumer demand in real terms will be modest. Incidentally, if Mr. Callaghan still believes in a wage-cost in- flation he is not crediting Mr. Brown with any success in his incomes policy.

As for a demand inflation, the estimated re- sources which will be available should be sufficient to take care of the increase in exports and investment, especially as investment is

bound to be cut back by the sharp rise in borrow- ing rates and the shock to business confidence which Mr. Callaghan's measures have caused. The Chancellor has, therefore, only to worry about government spending and this he can cut back without having to resort to extra taxation. Indeed, he told the Overseas Bankers' Club on Monday that 'my aim is to keep public expendi- ture within a definite limit, so as to prevent the total demand made upon our resources from becoming excessive.'

This is sound policy. I have no doubt that he will secure some worthwhile economies. He does not have to use the blunted axe of dear money and excessive taxation.

We all know that the government spending programme falls heavily on the building and contracting industries, which are already over- strained. Here again it is not necessary to relieve the pressure by keeping Bank rate up to 7 per cent or income tax up to 8s. 3d. or corporation tax up to 40: per cent. The housing programmes of the local authorities are already subject to Mr. Crossman's approval at the Ministry of Housing. The office- and flat-building projects of private enterprise can be equally subjected to central control by requiring them to obtain an industrial certificate at the Board of Trade. Even private building can be checked by instructing the local surveyors not to pass building plans above, say, the 1963-64 level. When I recommend these simple and pradticable forms of building control, I do not know whether I am preaching to the converted or to the lapsed. A building con- trol used to be an essential of Labour's economic policy. Mr. Callaghan would be wise to return to it and forswear the apparatus of Treasury deflationary budgeting with its false estimates and over-conservatism.

Here is a final word of advice which I hope Mr. Callaghan 1\ ill not ignore. He has it within his power to restore confidence in the City and the business world by an act of grace and understanding. The time is favourable. The £ is stronger, the trade returns are better, the spring revival in domestic trade is not far off and the hour approaches when Bank rate can be reduced to 6 per cent and the import surcharge to 121 per cent (or_even 10 per cent). But the people who use, make and earn money are still suspicious because Mr. Callaghan has threatened their livelihood and their net profits. What is more, the vast funds of the life assurance com- panies, whose net increment is at the rate of £12 million a week, are not being employed in the gilt-edged market as they should because Mr. Callaghan cannot yet define their taxation because he is waiting on the words of wisdom which may fall from the academic oracle at Somerset House. Is the London money market to stand still while Cambridge thinks? Is gov- ernment long-term credit to remain at 61 per cent and the biggest housing authority in the world —the LCC--forced to borrow at 61 per cent be- cause a highly complicated question of taxation —which no one outside the 'actuarial world can understand—cannot be settled in a rush? I im- plore Mr. Callaghan to use his common sense and tell the life assurance managers that it will be April 1966 before the 'special consideration' he has promised them can be completed. Then many

hundreds of millions will roll into British gov- ernment funds-foreign money will pour into our short-dated bonds-and the restoration of business confidence and government credit will march hand in hand.

Previous page

Previous page