Exhibitions 2

John Craxton

(Pallant House, Chichester, till 17 January)

Surprise pleasures

Andrew Lambirth John Craxton (b. 1922) is one of the hid- den treasures of English art. Although an exact contemporary of Lucian Freud, with whom he once shared a studio, he is hardly known in this country. (His evocative dust- jackets for the books of Patrick Leigh Fer- mor are often admired without this affecting his anonymity.) Admittedly, he is a very private painter, but his work is of such distinction, and so convincingly itself, that it deserves to be widely seen and appreciated. The current exhibition of some 40 paintings, dating from 1941 to the present, is an unmissable introduction to his chief concerns.

Craxton grew up on the visionary images of William Blake and Samuel Palmer, and was encouraged in his pursuit of the pas- toral by the wartime English Neo-Roman- tics. Much influenced by the landscapes of Graham Sutherland, Craxton began to paint the kind of Mediterranean terrain that he yearned for. After the war he was able to travel, and to discover his ideal landscape — in Greece. He moved to Crete in 1960, and has lived there for much of the time since. A man of considerable learning, he has appropriated those ele- ments of past art which best suit his ends, whether it be the rigorous structure of a Poussin painting or the formalism and flat- ness of 11th-century Byzantine mosaics.

One of the delights of this show is to watch such an acute intelligence working through the various possibilities and influ- ences which faced a young painter of his generation. Alongside the Neo-Romanti- cising was a keen awareness of what Mir6 and Picasso were up to. And as a necessary counterweight to the figurative tradition there was the inspiration of Mondrian and friendship with Ben Nicholson.

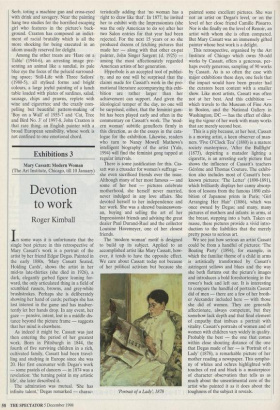

This exhibition contains some real sur- prises, not least in the early work. The frondy green spirits of nature emerge in a 1943 oil entitled 'Metamorphic Willow and Moon', but Sutherland and Mir6 are robustly paramount in the rather beautiful `Red and Yellow Landscape' of two years later. A densely worked pen and wash 'Cart Track, 1943, by John Craxton : an English painter with a broad European sensibility drawing from 1941 called 'Poet in Land- scape' features a mass of turbulent foliage threatening triffid-like to engulf the oblivi- ous reading poet, perhaps representing his dark desires or the pulsing tendrils of his imagination. Craxton's work possesses an impressive vitality of line, equally capable of great intricacy and of simple statement. Look at the extraordinary distortions of scale in 'Figure in a Grey Landscape' (1945), all drawn with such ravishing sim- plicity.

It is appropriate on two counts that John Craxton should now be exhibiting in Pal- lant House, the only Queen Anne town house in England open to the public. Its handsome spaces contain substantial bequests from two important collectors Walter Hussey and Charles Kearley — and weight the permanent collection towards Modern British. Craxton is entirely at home among works by Moore and Piper, Hitchens and Nash, while the relationship with Sutherland and Nicholson is especially close. The other reason is that Craxton came to study at the Prebendal Choir School in Chichester, 67 years ago. He already knew and loved the town, but did not take kindly to being a chorister in the cathedral. His great solace was the discov- ery of art, to which he experienced what he calls 'a Pauline conversion'. In particular, he was spiritually and emotionally upheld by two exquisite 12th-century Romanesque bas reliefs in the cathedral, on the subjects of Christ's Entry into Bethany and the Raising of Lazarus, which proved to him that great art was ageless and didn't have to mimic nature to look real.

Many of Craxton's earlier works depict imaginary landscapes. 'Cart Track' of 1943 is all violent greens and strange wart-like growths of herbage, as if the English land- scape had suddenly been subjected to a Mediterranean climate. Even the two very beautiful paintings of tree roots by a Welsh estuary (from 1943-4) are more stylised than overtly descriptive, though less angu- lar than the later work and altogether more organic. In recent years, Craxton has changed from using oil paints to acrylic tempera, achieving a drier surface, the colours somewhat chalkier. He paints the patterns of plants and trees, of stone walls, of clothing and features in a highly for- malised way. (He has a wonderfully eco- nomic means of drawing the nicks and folds of cloth or the clench of fingers.) Each object is encoded within the next to produce a lastingly harmonious effect.

Craxton is something of a hedonist, but he also wants other people to derive plea- sure from his work. The characters depict- ed in his paintings are usually sympathetic — a Cretan boy playing a lyre, sailors feast- ing or reclining at ease, shepherds or goatherds going about their daily business — but in 'Soldier with Slivovitz', painted over the last two years, he comes near to making a harsh political comment. Here Craxton has depicted an evilly squinting Serb, toting a machine gun and cross-eyed with drink and savagery. Near the painting hang two studies for the horrified escaping girl who features in the picture's back- ground. Craxton has composed an indict- ment of racial brutality which is all the more shocking for being executed in an idiom usually reserved for delight.

Among the other treats are 'Hare on a Table' (1944-6), an arresting image pre- senting an animal like a sundial, its pale blue eye the focus of the pelucid surround- ing space; 'Still-Life with Three Sailors' (1980-5), all stylised forms and bright colours, a large joyful painting of a lunch table loaded with plates of sardines, salad, sausage, chips and prawns, replete with wine and cigarettes; and the crazily com- pelling but beautiful pattern-making of `Boy on a Wall' of 1955-7 and 'Cat, Tree and Bird No. 3' of 1997-8. John Craxton is that rare thing: an English painter with a broad European sensibility, whose work is not confined to one emotional chord.

Previous page

Previous page