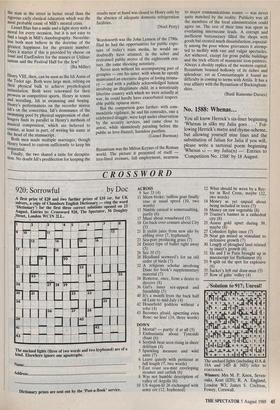

COMPETITION

Odious comparisons

Jaspistos

In Competition No. 1585 you were in- vited to supply a piece of prose beginning `Byzantium was the Milton Keynes of the Roman world' or with a similarly grotesque geographical or historical comparison.

My blurb continues: 'Paul Hetherington describes the many human elements that made up the city of Byzantium, the wise and selfish emperors . . . . the stylites per- ched for years atop their pillars, and the eunuchs who rose to positions of great power.' Rattling good history, eh? Com- petitors proved imaginative comparers. `Partridge Siding, British Columbia, is the modern Phoenicia' (Michael Heber- Percy), 'John Bunyan was the Salman Rushdie of 17th-century England' (Brian Ruth), and 'Delphi was the El Vino of ancient Greece, considered by local scribes the centre of the universe, the exact site being marked by a slate' (John O'Byrne). The best-crafted sentence came from John Digby: 'Each abounds in cats; but whilst Venice's slink and cower in every corner and alley, Docklands' float by from the upper waters of the Thames, rigid, legion and dead.'

The prizewinners below have £15 each, and the bonus bottle of Lamberhurst 1986 Seyval Blanc Dry English Wine, presented by Stephen Skelton of Lamberhurst Vineyards, goes to Andrew McEvoy.

The parallels between the careers of Edward Heath and Napoleon Bonaparte bewilder by the sheer extravagance of their proliferation. Both originated at peripheral points (Broadstairs/ Corsica) of the nations they so splendidly

Served. Both first won notice as dashing young officers. Both conquered Europe: Napoleon in the gross and vulgar sense of actually subduing it by force of arms; Heath in the more subtle and insidious fashion of insinuating the UK into the EEC after long years of frustrated importunity. Both seemed, for long, unassailable. Both were eventually undone by the machinations of General Winter: Napoleon by the ferocious, frosts and snows of Russia in 1812/1813; Heath by the fateful February of 1974, with the remorseless pickets of the NUM playing the role of the Cossacks who had harassed the Grand Army to its doom. Napoleon launched his comeback from Elba: Heath broods on his in Mompesson Close, Salisbury..

(Andrew McEvoy) John Stuart Mill is the thinking man's Lionel Blue. The same philosophy may be attributed to both these men although Mr Mill's discovery of the principle of utility was gleaned from Benth- am whereas Mr Blue absorbed his beliefs at his granny's knee. No matter. Indeed it may be argued that a kitchen philosophy would stand the man in the street in better stead than the rigorous early classical education which was the most probable cause of Mill's mental crisis.

Lionel Blue has a smile and a light story with a moral for every occasion, but it is not easy to find a laugh in Mill's Autobiography. Neverthe- less both men believe in the doctrine of the greatest happiness for the greatest number. Does it matter if this is provided by cheese on toast and EastEnders for the masses or Utilitar- ianism and the Festival Hall for the few?

(Ba Miller) Henry VIII, then, can be seen as the Idi Amin of the Tudor age. Both were large men, relying on their physical bulk to achieve psychological intimidation. Both were renowned for their prowess in competitive sports, Henry in tennis and wrestling, Idi in swimming and boxing. Henry's performances on the recorder mirror Idi's on the concertina. Idi's dominance of the swimming Pool by physical suppression of chal- lengers finds its parallel in Henry's methods of Musical composition, which are believed to consist, at least in part, of writing his name at the head of the manuscript. Both men made multiple marriages, though Henry bowed to custom sufficiently to keep his sequential.

Finally, the two shared a taste for decapita- tion. No doubt Idi's predilection for keeping the results near at hand was closed to Henry only by the absence of adequate domestic refrigeration facilities.

(Noel Petty) Wordsworth was the John Lennon of the 1790s. Had he had the opportunities for public expo- sure of today's mass media, he would un- doubtedly have attained, in the sober and restrained public mores of the eighteenth cen- tury, the same shocking notoriety. Never seen without his accompanying pair of groupies — one his sister, with whom he openly maintained an excessive degree of loving intima- cy — and with a publicly acknowledged liaison involving an illegitimate child, in a notoriously libertine country with which we were actually at war, he could hardly have exacerbated respect- able public opinion more. But the comparison goes further: with com- mendable vigilance, he and his comrades, one a celebrated druggie, were kept under observation by the security services, and came close to arrest, while shamelessly parading before the public as love-fixated, harmless pacifists, (Lionel Burman) Byzantium was the Milton Keynes of the Roman world. The picture it presented of itself tree-lined avenues, full employment, nearness

to major communications routes — was never quite matched by the reality, Publicity was all the members of the local administration could agree on. The rest of their time was spent in everlasting internecine feuds. A corrupt and inefficient bureaucracy filled the shops with goods but created much dissatisfaction, especial- ly among the poor whose grievances it attemp- ted to mollify with vast and vulgar spectacles. Art withered, except for gross public buildings and the trick effects of mannerist icon-painters. Always a shoddy replica of the western capital, Byzantium boasted hollowly of its riches and splendour; yet as Constantinople it found no difficulty in coming to terms with Attila. It has a true affinity with the Byzantium of Buckingham- shire.

(Basil Ransome-Davies)

Previous page

Previous page