Scapegoats of history

Byron Rogers

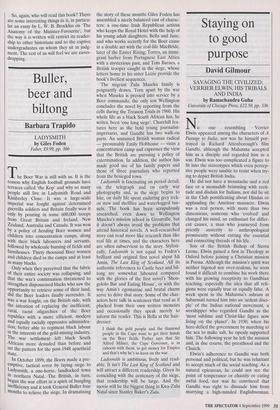

THE WORLD OF THE FAVOURITE edited by J. H. Elliott and L. W. B. Brockliss Yale, £35, pp. 320 For most of the 16th and part of the 17th century, many European states were controlled by the grandest and edgiest figures in political history, men rul- ing with no power base other than the favour of the hereditary prince who had raised and could at any moment break them. These shooting stars lived like kings, George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham by William Larkin, 1616 (National Portrait Gallery) which was a way of concealing that it all turned on charm, force of personality and the ability to make themselves seem indis- pensable. They had no army and no politi- cal party: there has never been a balancing act like theirs.

This book consists of essays by 18 profes- sors and lecturers from America to War- saw, whose specialist subject this is, and who, if assembled in one room, would know all there was to be known about Richelieu, Buckingham, et al. And they did assemble in one room, in Oxford, where they read these papers to each other. So who will read their book?

It is sad that that question even has to be asked, given its theme. Just think of the dramatic potential of the minister- favourite, a man enjoying something close to absolute power, but only at the whim of some cold dynast who had come in from the battlefields to the catwalk of his splen- did court. Mrs Thatcher lives on: the scaf- fold awaited the favourite when his prince threw him to those who hated him. And he was hated as much as any man was hated.

Even now when Richelieu appears in a film, every actor, with the exception of the strange George Arliss, has portrayed him as a baddy, while those thugs, the Musketeers, go their merry way. But then it was Richelieu who stopped the murderous duelling which was the curse of the French court but the delight of cinema audiences everywhere.

It was part of the favourite's function to be hated, to deflect attention away from the dynast whose power base he was assem- bling. The old nobility, whose power he was dismantling, hated him; parliaments, whose growing power he blocked, hated him. As Wentworth said, in his usual dour way, after the assassination of Buckingham, 'It is said at Court there is none now to impute our faults unto . . .' The irony was that he himself was to fill the role, and be judicially murdered for it.

Who were these men? Their kings were not masterful enough to pick a butcher's boy, like Henry VIII, or eccentric enough, like Louis XI, to recruit their own barbers. Richelieu and the Spaniard Olivares were already noblemen and even George Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham to be, was from the gentry, and George had legs like Naomi Campbell. But Buckingham apart, the favourites had one thing in com- mon — their capacity for work. Their care- fully chosen backcloth may have been splendid palaces and commissioned por- traits from Old Masters, but the lasting image of the favourite is the Count-Duke de Olivares scurrying around the palace, state papers stuck in his hatband, others dangling from his waist, looking like a scarecrow. Another is of Olivares kissing his master's chamber pot. These were the realities of the favourite's position, and the reasons it did not become hereditary like the shogunate in Japan.

So who will read this book? Its form is against it from the start, being papers read by historians to other historians, who already know the anecdotes. One example: some of them refer to the Day of Dupes, the most dramatic single incident in the career of a favourite, in this case Richelieu. The Queen Mother of France, having got her ailing son's promise to dismiss the Car- dinal, summoned the King to a meeting in a guarded room. But Richelieu, knowing a secret entrance, suddenly materialised in their midst. He was thrown out, but waited on the stairs where, in full view of the court, he was cut by the King. It was the moment his enemies had been waiting for, the Cardinal was finished. But that night, even as they celebrated, the King in his hunting lodge quietly sent for Richelieu to reassure him that nothing had changed. It is pure extravagant Hollywood, but it hap- pened. The only thing is that it does not happen in this book, where the historians merely feel the need to make a passing ref- erence, like old comics in a conference of their peers referring to a punch-line, the joke being already known to the assembly. Gibbon would not have passed up a chance like that.

Again you are put off by that nervous need in some historians to be nice to their colleagues. 'As Professor Bloggs has so neatly put it, echoing the trenchant case advanced by Dr Cloggs, whose points have been borne out by the research done by Professor van Dogget . . In one para- graph alone, Professor David Wootton of London University recommends the works of nine other historians, but does not say why. Presumably, again, his audience was already familiar with their papers.

Count Duke of Olivares by Diego Velazquez, c. 1625 (Hispanic Society of America, New York) Then there are the footnotes, 156 alone following Professor Blair Worden's `Favourites on the English Stage' like the trail of a comet. His essay has 15 pages of text, eight of notes, almost all of which list books, for the academic historian has to guard his back as well as patronise his col- leagues. His position has thus something in common with that of the favourite; the rewards may not compare, but his job secu- rity does. So, again, who will read this book? There are some interesting things in it, in particu- lar an essay by L. W. B. Brockliss on 'The Anatomy of the Minister-Favourite', but the way it is written will restrict its reader- ship to other historians and to the captive undergraduates on whom they sit in judg- ment. The rest of us will feel we are eaves- dropping.

Previous page

Previous page