Cinema

4,

Kids' Stuff

By ISABEL QUIGLY Blue Jeans. (Rialto.)—Upstairs and Downstairs, (Odeon, Marble Arch.)—The Naked Maja. (Empire.)—A Private's Affair. (Carlton.) THEY don't, as far as I remem- ber; wear blue jeans all the time in Blue Jeans (director : Philip Dunne; 'X' certificate), or even mention them, but you can see what they mean by the title. The term has become an international label, even outside English-speaking countries, for teenagers, and mixed-up teenagers in particular.

Blue Jeans is mild sociology : banal, credible enough, not very illuminating because very much too obvious. You know it all already—the mixed- up families, on the surface happy enough, the gulfs between parents and children—as you know what is going to happen, since it has all happened so often in films before. From their first fumbling conversation on the subject, you know the boy and girl, both about sixteen, are going to make love pretty soon; and that the girl will become pregnant; and that they won't tell their parents, and will make frantic efforts to get an abortion. When the girl goes off in a kind of Black Maria with a bandage over her eyes and a sinister woman to guard her you know very well the boy will break down and tell his parents; and when the parents' car dashes through the night to find her you know (as clearly as in The Perils of Pauline) that they'll get there in time. When the girl, decides to leave the boy free so as not to handicap him, and run off to have her child in secret, you know again he'll follow her and (suddenly manly and decisive, instead of cowardly and floundering) insist on marriage. And so on, and so on. Just as you know the misunderstanding parents will all have changes of heart and recognise that it was all, in some way, their fault. There is absolutely nothing surprising in any of it; and no one ever does, feels or says anything in the least outside the conventions of film behaviour.

What makes rather more of it than you might expect is the acting of the two young people, Brandon de Wilde and Carol Lynley. I last saw Brandon de Wilde as a child actor, much taken up with dogs; and Carol Lynley for the first time two weeks ago, much taken up, in Holiday for Lovers, with her first taste of male admiration. They are both round-faced and very vulnerable, clearly the right age. There is, especially, a babyish pathos about Carol Lynley's fat face and rat's-tail hair that is far more effective, in this case, than beauty; and it shows one how impossible it is for actresses even a very few years too old to get the right teen- age movements, skin, attitudes. The parents seem exaggerately tiresome; or are all parents so, from a teenage point of view? That seems to me the only sobering thought about this otherwise very unprovoking and uncontroversial film.

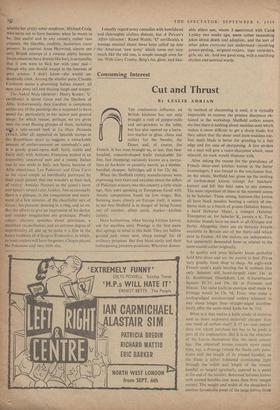

The Rank comedy, Upstairs and Downstairs (director : Ralph Thomas; 'A' certificate), is about another of those life-in-Britain-today problems : servants. Richard and Katherine get married, only to discover the perils of domestic life if you can't or won't do your own housework. Katherine has a baby, then another, and no sooner claps eyes on them than she shrieks, like the good middle-class British mummy she is : 'Help! Find me a nanpy ! ' and dashes back to her job at the BBC. So they run through every sort of domestic appliance you can think of : bibulous cook, burglarious married couple, wild woman from Wales, Italian glamour girl who calls in the US Navy, etc. etc.; and finally settle on one of those foreign girls who are not quite maids and not quite anything else and dis- rupt the domestic peace of so many families these days : gorgeous Ingrid, in this case, from Sweden. It is Ingrid who enlivens this routine little piece* (which has almost every British film face you can think of in it somewhere or other, and pretty well every British film joke as well); and gives the last half-hour a lightness, even a touching quality, noticeably missing from the rest. Mylene Demon- geot, who plays her, is quite the most attractive thing that has strayed into British films for ages, a mixture of softness, ruthlessness, gaiety, and sheer blonde juvenile good looks that almost over- whelms her pretty sober employer, Michael Craig, who turns out to have become, when he wants to be, that useful and in any country rather rare creature, the likeable, credible, humorous jeune premier. In contrast Anne Heywood, almost our only British attempt at a routine pretty heroine (most countries have dozens like her), is so metallic that if you were to flick her with your nail— though why you should, except in the interests of pure science, I don't know—she would un- doubtedly clink. Among the smaller parts, Claudia Cardinale seems a promising Italian import, all eyes and pony tail and blazing laugh and temper.

The Naked Maja (director : Henry Koster; 'U' certificate) is about Goya and the Duchess of Alba. Unfortunately Ava Gardner is completely unlike any of the paintings she is supposed to have posed for, particularly in her stance and general shape: for which reason, perhaps, we are given only the most fleeting glimpes of them, including sth a split-second look at La Maja Destutita (which. after all, appeared on Spanish stamps in the Republican days) as suggests a remarkable amount of embarrassment on somebody's part. It is gawdy grand-opera stuff, fairly risible and fairly dull; with Anthony Franciosa wasted in an impossibly conceived part and a mostly Italian cast (it was made in Italy, not Spain, because of Alba objections); Lea Padovani and Gino Cervi as the royal couple so horrifically portrayed by their court painter that one wonders at their lack of vanity: Amedeo Nazzari as the queen's lover and Spain's virtual ruler, Godoy. Just occasionally there is a glimpse, in the composition and move- ment of a few minutes, of the chcerfullcr sort of Goya : his peasants dancing in a ring, and so on. But the efforts to give an impression of his darker and madder imagination are grotesque. Plushy colour. plummy speeches about patriotism, a deathbed reconciliation, and an extreme degree of superficiality all add up to make it a film in the hoary tradition of A Song to Remember, in which, as most readers will have forgotten, Chopin played the Polonaise and very little else. I usually regard army comedies with bewildered and thoroughly civilian distaste, but A Private's Affair (director : Raoul Walsh; 'U' certificate), a teenage musical about three boys called up into the American 'new army' which turns out very much like the old one, is simple enough even for me. With Gary Crosby, Bing's fat, glum, and like- able eldest son, whom I mentioned with Carol Lynley two weeks ago, some rather nauseating jokes about death and adoption, and the sort of other jokes everyone can understand—involving potato-peeling, sergeant-majors, tape recorders, girls, etc. etc. And one good song, with a marching rhythm and satirical words.

Previous page

Previous page