Days and Nights on Service. By Major A. E. De

Cosson. (John Murray.)—There is no need for the somewhat apologetic tone of Major De Cosson's preface. He tells us exactly what we want to bear, the daily details of a soldier's life on service. They are things which we, "who sit at home at ease" (if there be such a thing as ease with General Elections twice a year, and books pouring from the Press by hundreds), are never wearied of. Major De Cosson reached Suakim early in the March of last year, and he left it on May 22nd, invalided. The time included is little more than ten weeks, but into these ten weeks were crowded the labours and sufferings of a long campaign. The story of these labours and sufferings is not a subject for criticism ; when we have said that it is told in excellent English—the writer is, iudeed, no novice with his pen—in a modest, manly fashion, we have done all that can be ex- pected from a reviewer,—exoept, indeed, it be to give our readers a hearty recommendation to make acquaintance with the volume for

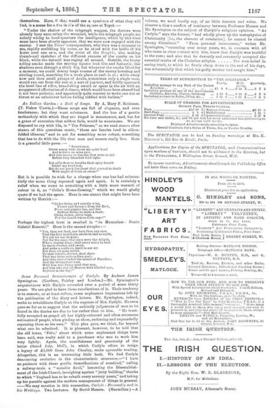

themselves. Here, if they would see a speciamn of what they will End, is a scene from the in dee of the striate at Topek :—

"Under the shelter of the telegraph waggon, the doctors were already busy encomring the wounded, while the telegraph people sat calmly wiring to bead-quarters the intelligence, which by this time must have been clearly apparent, that we were now engaged with the enemy. I saw the Times' correspondent, who then was a stranger to me, rapidly scribbling his notes, as he stood with the bridle of his horse over one arm, and the artist of the Graphic, also making thumb-nail sketches of the different corners of the zareba on his block, while the turmoil was raging all around. Outside, the heavy rolling smoke made the moving figures look dim and fantastic, like shadows seen through a thick fog, but whenever the smoke lifted for a moment, we could descry large masses of the enemy hovering and circling round, searching for a weak place to rush in at ; while every now and then small groups of Arabs, sometimes only a single man, would run out from the rest at a sort of jog-trot, and boldly approach the level line of rifles, brandishing sword or spear in the air with an exaggerated affectation of defiance, which would have been absurd had it not been pathetic, and apparently quite content to make one cut or thrust at an unbeliever before falling riddled with bullets."

Previous page

Previous page