ARTS

Architecture

The spirit of '51

Alan Powers on the future of the South Bank 40 years after the Festival of Britain The 40th anniversary of the Festival of Britain, which falls this week, offers little cause for comfort or rejoicing. So many of its promises for architecture and planning failed to materialise, and its assurances that the experts knew best were so soon betrayed. The reasons for this inescapable downbeat mood are worth investigating.

English architecture (Scotland is a wholly different story) has more often than not been pulled in two contrary directions. On one hand, the austere character of abstract architectural form offers a hard and thank- less road to virtue. On the other, pic- turesque stylism, decoration and borrowed motifs can become a substitute for archi- tecture itself. The complication is that these apparent opposites are nearly always found together, one substituting for anoth- er. Thus the English Palladian movement of the 18th century, under the guise of for- mal discipline, readily became a formula lacking all the architectural vitality of Palladio himself. The Greek Revival, with a few exceptions, became tedious rhetoric rather than epic or lyric.

The circulation spaces of the Royal Festival Hall continue to demonstrate what must always have been the architectural high point of the Festival, where ratio- nal planning and spa- tial imagination worked together.

Apart from this, the Picturesque inflection of modern architec- ture was already seen as the means of angli- cising it, and the result was the soon- despised `Contem- porary Style'. Qualities that made fine exhibition architecture were too facile to be Pleasing elsewhere, although the bread- and-butter building of the Festival's model development of Lansbury in Poplar has stood the test of time remarkably well. At the cakes-and-ale extreme, the Festival Pleasure Gardens at Battersea would undoubtedly now be enjoying a cult revival had they been allowed to prosper and sur- vive. London still needs its own version of Copenhagen's Tivoli, which in Eric de Mare's words 'achieves the impossible — democratic gaiety without vulgarity'. One wishes that architects had more often defied the moralistic critics and allowed themselves liberties like the free-curved roof canopy on the top of Great Arthur House in the Golden Lane Estate, north of the Barbican.

On the South Bank site, although all the buildings except the Festival Hall were so Kitchen, by Bob Pendered and Rex Garrod: part of The Ride of Life', a masterpiece by 20 contemporary British automatists which could enliven the South Bank notoriously cleared away, they left in the national architectural memory a sowing of 'Contemporary' dragon's teeth which was reaped in the group of buildings compris- ing the Queen Elizabeth Hall, Purcell Room and Hayward Gallery, opened in 1965. These represent the younger genera- tion's reaction against the spindly mod- ernism of the Festival: black leather instead of tweed. Yet the defiance came too late, and was even more flawed by indulgence in anti-picturesqueness. The possible profit of a valid architectural reaction was side- tracked into posturing. These are amongst the least-loved buildings in London, so that when the South Bank Board employed Terry Farrell to produce schemes for wrap- ping them up as post-modern parcels, they expected widespread support.

At Farrell's presentation of his proposals for the whole South Bank site in the sum- mer of 1989, the RIBA was picketed by students with placards saying 'Save Brutalism' — a minority view, but one which recognises the continuing service- ability of these sullen monsters. The Farrell proposals, currently being resubmitted in modified form, attempt to deal both with the comfort of the public on the South Bank and the comfort of the South Bank Board's budgets by generating income from the development of shops. Local activists from the Coin Street side, and ex-GLC architects from the County Hall side, are suspicious of the commercial exploitation inherent in the scheme. Aesthetically, Farrell's claim to be reviving the colourful spirit of the Festival is equally suspect. It is a misappropriation of style — a temporary exhibition site and a permanent national cultural centre are different things. The looming presence of the Shell Centre has irrevocably altered the character of the site since 1951, and the uncertain future of County Hall pre- vents the planning of a unified scheme from Westminster to Waterloo Bridges.

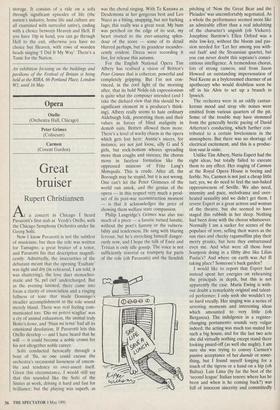

Thus the South Bank has become yet one more focus for desultory debate on the lost opportunities of the capital's archi- tecture and planning. Will the public expe- rience a net gain from the Farrell scheme, and will it seem only a piece of outdated 1980s thinking by the time it is actually built? It might be more in the spir- it of the 1951 Festival to improvise responses to the site, rather than aim for a total solution. Temporary structures and uses, art installations and performances could expand the already flourishing activi- ties inside the Festival Hall. An opportun- ity exists for providing art and entertain- ment together if it were possible to install 'The Ride of Life', a composite master- piece by contemporary British automatists, commissioned for Meadowhall Shopping Centre, Sheffield, but now languishing in

storage. It consists of a ride on a sofa through significant episodes of life (the nation's industry, home life and culture are all examined with surrealist satire), ending with a choice between Heaven and Hell. If you have 10p in hand, you can go through Hell to the exit, otherwise you have no choice but Heaven, with rows of wooden heads singing 'I Did It My Way'. There's a Tonic for the Nation.

Previous page

Previous page