Cinema

Pret-a-Porter (`15', selected cinemas) The River Wild ('l2', selected cinemas)

No room for jokes

Mark Steyn

To those of us who admired Short Cuts, fret-a-Porter is a shocking reminder of the limitations of the Robert Altman school of film-making. To begin with, you can't satirise industries that are inherently self- satirising: they make all the best jokes themselves. For example, no savage indict- ment by a left-wing dramatist would have cooked up a 28-year old trader who in three days sends the City's oldest bank into a billion dollar meltdown. All you can do with such groups is flatter 'em — as the insider audiences at Caryl Churchill's Seri- ous Money or the Hollywood acclaim for Altman's The Player illustrate.

The problem with his take on the fashion world is that it isn't knowing enough: it looks as if he just switched on Channel 73, saw some airhead reporter at the Paris col- lections and scoffed, 'Jcez, this gets more ridiculous every year.' But the guy on the next bar stool can tell you that; you don't need Altman to do it. Undeterred, the inci- sive ironist — accompanied by Julia Roberts, Sophia Loren, Marcello Mas- troianni, Kim Basinger, Lauren Bacall, Tim Robbins, Anouk Aimee, Cher and more heads for Paris, takes a sledge-hammer to a powder puff and emerges with the amazing revelation that the fashion industry is bitchy and shallow. Let he who is without sin cast the first stone.

Instead, Altman casts the first star: Basinger as, lees see, a TV bimbo; then

Stephen Rea as an Irish snapper; and, hmm Roberts and Robbins as press reporters; and Tracey Ullman, Sally Keller- man and Linda Hunt as editors of Vogue, Harper's and Elle. Just as folks go to Paris fashion week because it's chic to be seen there, so stars flock to Robert Altman movies because they're chic to be seen in: you can just swan around and nobody pays much attention to the clothes. In fact, as the dramatis personae indicates, Altman couldn't give a hoot about hemlines: he's interested in how the media cover fashion. So there are lots of excruciatingly inept interviews from Basinger and her roving mike. Except that this star's idea of a crass reporter is itself crass. Watching Holly- wood's aristocracy pretending to be the poor bloody infantry of the entertainment world is a bit like catching the Royal Fami- ly doing impressions of their servants: every character is patronised, caricatured, so that ten minutes into the picture there's nowhere to go.

Don't take it so seriously, says Altman, it's a farce. But farce is the most disciplined of forms, and Altman is too fond of his own indulgences to learn it. Farce is tightly plotted and hound by its own ruthless logic; Altman prefers plotless, loosely linked montages. Farce has taut, heightened dia- logue driving the situation onward; Altman threw out Barbara Shulgasser's script and opted for the usual overlapped, inaudible, improvised dialogue. But you can't ad lib a farce, particularly when you're shooting it during fashion week and have, more or less, to do it in real time. There are too many moments in this film when you can see the actors trying to think of what to say next, and in those multiple split-seconds the crucial ingredients of farce — tempo and energy — bleed away.

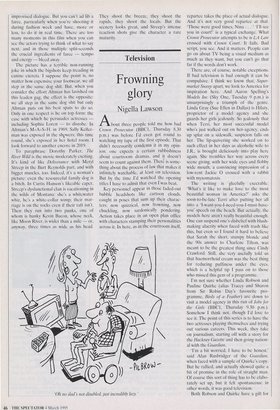

The picture has a terrible non-running joke in which the bigshots keep treading in canine excreta. I suppose the point is, no matter how expensive your footwear, we all step in the same dog shit. But, when you consider the effort Altman has lavished on this leaden gag, the effect is the opposite: we all step in the same dog shit but only Altman puts on his best spats to do so. Only in one respect is he on top form: the ease with which he persuades actresses including Sophia Loren — to disrobe. In Altman's M*A*S*H. in 1969, Sally Keller- man was exposed in the shovers; this time round, she's exposed in her hotel room. I look forward to another encore in 2019.

To paraphrase Dorothy Parker, The River Wild is the movie moderately exciting. It's kind of like Deliverance with Meryl Strccp in the Burt Reynolds part, and with bigger muscles, too. Indeed, it's a woman's picture: even the resourceful family dog is a bitch. In Curtis Hanson's likeable caper, Streep's dysfunctional clan is vacationing in the wilds of Montana: she's a whitewater whiz, lie's a white-collar wimp; their mar- riage is on the rocks even if their raft isn't. Then they run into two punks, one of whom is hunky Kevin Bacon, whose neck, like Moon River, is wider than a mile — or, anyway, three times as wide as his head.

They shoot the breeze, they shoot the rapids, they shoot the locals. But the scenery looks great, and Streep's intense reaction shots give the character a rare maturity.

Previous page

Previous page