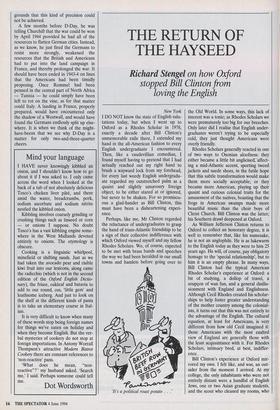

THE RETURN OF THE HAYSEED

stopped Bill Clinton from loving the English

New York I DO NOT know the state of English salu- tations today, but when I went up to Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar in 1978, exactly a decade after Bill Clinton's unmemorable exile there, I extended my hand in the all-American fashion to every English undergraduate I encountered. Then, like a vaudevillian comedian, I found myself having to pretend that I had actually reached out my right hand to brush a wayward lock from my forehead, for every last weedy English undergradu- ate regarded my outstretched palm as a quaint and slightly unsavoury foreign object, to be either stared at or ignored, but never to be shaken. For so promiscu- ous a glad-hander as Bill Clinton, this must have been a disheartening experi- ence.

Perhaps, like me, Mr Clinton regarded the reluctance of undergraduates to grasp the hand of trans-Atlantic friendship to be a sign of their collective indifference with which Oxford viewed myself and my fellow Rhodes Scholars. We, of course, expected to be met with brass bands and speeches the way we had been heralded in our small towns and hamlets before going over to `It's a political roast potato . . . the Old World. In some ways, this lack of interest was a tonic; as Rhodes Scholars we were prematurely too big for our breeches. Only later did I realise that English under- graduates weren't trying to be especially cold, they just thought Americans were overly friendly.

Rhodes Scholars generally reacted in one of two ways to Oxonian aloofness: they either became a little bit anglicised;-affect- ing a mid-Atlantic accent, sporting tweed jackets and suede shoes, in the futile hope that this subtle transformation would make them more socially acceptable; or they became more American, playing up their quaint and curious colonial traits for the amusement of the natives, boasting that the frogs in American swamps made more beautiful music than the choir boys of Christ Church. Bill Clinton was the latter; his Southern drawl deepened at Oxford.

As William Jefferson Clinton returns to Oxford to collect an honorary degree, it is well to remember that, like his namesake, he is not an anglophile. He is as lukewarm to the English today as they were to him 25 years ago. He will, of course, pay obligatory homage to the 'special relationship', but to him it is an empty phrase. In many ways, Bill Clinton had the typical American Rhodes Scholar's experience at Oxford: a bit of studying, a dollop of travel, a soupcon of wan fun, and a general disillu- sionment with England and Englishness. Although Cecil Rhodes created his scholar- ships to help foster greater understanding of the mother country among the colonial- ists, it turns out that this was not entirely to the advantage of the English. The cultural equation, at least for Americans, is very different from how old Cecil imagined it: those Americans with the most exalted view of England are generally those with the least acquaintance with it. For Rhodes Scholars, intimacy bred, at best, indiffer- ence.

Bill Clinton's experience at Oxford mir- rored my own. I felt like, and was, an out- sider from the moment I arrived. At my college, the only inhabitants who were not entirely distant were a handful of English Jews, one or two Asian graduate students, and the scout who cleaned my rooms, who informed me that I was the first person at the college to ask him his Christian name in over 20 years. Americans in general, and Rhodes Scholars in particular, formed their own social ghetto at Oxford. We ate together, travelled together, and com- plained about the Brits together.

I confess that, unlike Bill Clinton, I bought a murky brown tweed jacket and some suede shoes, and did my best to modify my New York accent. It didn't do much good; I was spotted as an impostor right away. I had never been abroad before, and to me, as a literature major, every Englishman was a lineal descendent of William Shakespeare. But my greatest American friend was a Rhodes Scholar from Oregon, who had precisely the oppo- site reaction to British stand-offishness. Although he was an extremely literate fel- low who was writing his dissertation on Tobias Smollett, he wore flannel shirts and behaved like a displaced lumberjack from the Pacific Northwest. He cursed and swore and did his best to embarrass timid English undergraduates with his mock cru- dity. 'You wouldn't say shit if you had a mouthful!' I remember him growling to a mortified undergraduate in the junior common-room.

Bill Clinton lived in a house in north Oxford with a bunch of American Rhodes Scholar cronies, quite a few of whom now hold high places in the Clinton administra- tion. He was not particularly interested in English culture or society, and there is no evidence that anything British wore off on the young man from Hope, Arkansas. In fact, by all reports he took delight in play- ing the innocent hayseed, the Mark Twain- ish naif from the South who was mystified by the highfalutin' ways of the Europeans.

In Clinton's day he was a victim of not only English cultural snobbism, but politi- cal condescension as well. In 1968, because of the Vietnam war, Americans in Oxford became political pariahs, the moral equivalent of white South Africans. For a young man like Clinton, who was already sensitive to the prejudices North- erners had about Southerners in America, and who was genuinely agonised about the war, this was an unpardonable slight.

But the truth is that, in general, Rhodes Scholars care very little about Oxford. England, alas, is the provinces. Rhodes Scholars are preternaturally ambitious creatures and, for them, the importance of a Rhodes Scholarship is not the experi- ence but the credential. That is the reason so many Rhodes Scholars, like Bill Clin- ton, don't bother to take a degree at Oxford. In America, which is the only locale they really care about, the degree or lack of one — is immaterial. Like Clin- ton, a great many Rhodes Scholars imme- diately go on to an Ivy League law school, and Oxford's legacy is little more than a few amusing anecdotes about scrambling over the college gate after curfew. For these young Americans, the two years at Oxford are a parenthesis of serendipity between teenaged precociousness and the middle decades of ladder-climbing. Oxford was a respite from responsibility, because whatever happened in the Old World didn't really matter in the new one.

Clinton once wrote home that he was impressed by the facility and fluency of English undergraduates. I was too, for a while. But I eventually learned that the sophistication was a façade. There are a great many Americans who are intimidated by an English accent, but Rhodes Scholars are not among them.

At the time, I felt that Oxford contrived to make the vices of privilege appear to be forms of virtue and that English undergrad- uates' claims to intellectual superiority, as Edmund Wilson once said, were based on identifying their inferior lives with the superior achievement of their dim ances- tors. But I no longer feel that way. I have simply become very impatient with Ameri- can anglophiles. And I suspect that Presi- dent Clinton shares my prejudice.

Richard Stengel is a contributing editor of Time magazine.

Previous page

Previous page