BOOKS

The man behind the beard

Colin Welch

SALISBURY, THE MAN AND HIS POLICIES edited by Lord Blake and Hugh Cecil Macmillan, f29.50 What those great bushy gravy- encrusted Victorian beards conceal from us! Not just Lear's birds but the men behind them, still more the young men who were there before they grew. Look at the famous portraits of Tennyson, say, Trollope, Brahms, Rimsky-Korsakov, other beavers. Who can believe, what their works defiantly assert, that here were men who had been young, tender, ardent, full of fun, love and aspiration? The contradic- tion is painful. How could men be so belied?

Looking at the familiar photographs of the old Lord Salisbury, we are not aware of any such contradiction. His great beard seems perfectly congruous, the fitting adornment of an elder statesman, a pat- riarch or Nestor, a serious, formidable and dignified defender of tradition and (in both senses) the right. He appears grave, wise and authoritative. So he was, indeed, and so exclusively we think of him as being, as if there were not always another and more approachable and mischievous Salisbury lurking, clean-shaven in the undergrowth.

The existence of this other Salisbury should not in fact be unknown to us. He appears fitfully in Lady Gwendolen Cecil's long, masterly but incomplete and perhaps over-reticent life of her father. He shines forth in all his idiosyncratic charm in the early pages of Kenneth Rose's life- enhancing account of The Later Cecils (Weidenfeld). He appears again at inter- vals in Lord Blake and Hugh Cecil's present compilation.

This is not in the same class as Rose, by which I mean nothing derogatory. For the most part it does not seek to be. Much space is devoted to detailed and technical analyses of aspects of Salisbury's thought and activity. The inter-relationship in his mind, for instance, between domestic fi- nance and foreign policy is thoroughly discussed. His caution in both fields is attributed to his overriding concern for the threatened survival of his own landed class. Modern Tories might profitably note that he thought defence spending largely waste- ful. Some Tories may be inwardly of the same mind still, but it does not do to say so when confronted by external enemies greater than Salisbury ever knew and an Opposition which, half in league with them, eschews defence altogether.

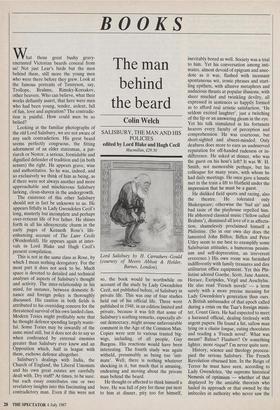

Salisbury's dealings with India, the Church of England, the Liberal Unionists and his own great estates are carefully dealt with. Dry stuff? At times, to be sure: but each essay contributes one or two revelatory insights into this fascinating and contradictory man. Even if this were not Lord Salisbury by H. Carruthers-Gould (courtesy of Messrs Abbott & Holder, Barnes, London).

so, the book would be worthwhile on account of the study by Lady Gwendolen Cecil, not published before, of Salisbury in private life. This was one of four studies held out of his official life. Three were published in 1948, in an edition limited and private, because it was felt that some of Salisbury's scathing remarks, especially ab- out democracy, might arouse unfavourable comment in the Age of the Common Man. Copies were sent to various trusted big- wigs, including, of all people, Guy Burgess. His reactions would have been interesting. The fourth study was again witheld, presumably as being too 'inti- mate'. Well, there is nothing whatever shocking in it, but much that is amusing, endearing and moving about the private man behind the beard.

He thought or affected to think himself a bore. He was full of pity for those put next to him at dinner, pity too for himself, inevitably bored as well. Society was a trial to him. Yet his conversation among inti- mates, almost devoid of epigram and anec- dote as it was, flashed with incessant spontaneous wit, ironic phrases and start- ling epithets, with allusive metaphors and audacious thrusts at popular illusions, with sheer mischief and twinkling devilry, all expressed in sentences so happily formed as to afford real artistic satisfaction. 'He seldom excited laughter', just a twitching of the lip or an answering gleam in the eye. Yet his talk stimulated in his fortunate hearers every faculty of perception and comprehension. He was courteous, but short-sighted and absent-minded. Only deafness does more to earn an undeserved reputation for off-handed rudeness or in- difference. He asked-at dinner, who was the guest on his host's left? It was W. H. Smith, not memorable perhaps, but his colleague for many years, with whom he had daily meetings. He once gave a lunatic met in the train a lift to Hatfield under the impression that he must be a guest.

He disliked field sports and racing, also the theatre. He tolerated only Shakespeare; otherwise the tad air' and bad taste of the playhouse repelled him. He abhorred classical music (`fellow called Brahms'), dismissed all love of it as affecta- tion, shamelessly proclaimed himself a Philistine. (So in our own day does the lamented John Biffen; Biffen and Peter Utley seem to me best to exemplify some Salisburian attitudes, a humorous pessim- ism and self-deprecation, an irreverent reverence.) His own room was furnished indifferently with family treasures and dire utilitarian office equipment. Yet this Phi- listine adored Goethe, Scott, Jane Austen, Horace, Euripides, Virgil and Aeschylus. He also read 'French novels' — a term surely with a more precise meaning for Lady Gwendolen's generation than ours. A British ambassador of that epoch called during a crisis on the Tsar's foreign minis- ter, Count Giers. He had expected to meet a harassed official, dealing tirelessly with urgent papers. He found a fat, sallow man lying on a chaise longue, eating chocolates and reading a 'French novel'. What was meant? Balzac? Flaubert? Or something lighter, more risque? I'm never quite sure.

History, science and theology preoccu- pied the serious Salisbury. The French Revolution obsessed him. In the Reign of Terror he must have seen, according to Lady Gwendolen, 'the supreme historical Nemesis of optimism — whether of that displayed by the amiable theorists who hailed its approach or that owned by the imbeciles in authority who never saw the storm coming till it was bursting over their heads'. This ever-present dark vision haunted Salisbury's profound pessimism. He saw himself perhaps as involved, like the Confederate General Joseph E. John- ston, in an unending rearguard action, in which vigorous counter-attacks could only lead to immediate disaster. As Ferdinand Mount has pointed out, his dogged defeat- ism would have made it impossible for him to inspire or even envisage Mrs Thatcher's popular optimistic Conservatism.

It was not for him always thus. His early journalism was full of fiery, intransigent and reactionary Hotspur rhetoric. Better a lost election, Kenneth Rose quotes him as trumpeting, than a Conservative belief compromised. He learned better, or worse; won more elections than any Con- servative Prime Minister between Lord Liverpool and Mrs Thatcher; sponsored or acquiesced in Liberal-inspired measures because they were the fashion; no arguing against them, his task only to accept defeat cordially, and to lessen the evils to which he had been 'forced to succumb'.

That early journalism was nearly all anonymous. He forbade even to his family all discussion of it, indeed any allusion to it in his presence. Why was this? Lady Gwendolen offers surmises: morbid re- serve, the reticence customary at that time, a desire to avoid 'annoyances' and con- troversy, the 'shyness' of authorship. There was certainly nothing to be ashamed of in the author's dashing and vivacious polemic style, the product of much labour and correction. Was the author perhaps nonetheless ashamed of the content? Did it become an embarrassment or inconveni- ence to the older, more cynical and worldly-wise Salisbury? Was the elder statesman shocked by what the other Salis- bury behind the beard had rashly commit- ted to paper?

The simple piety of this complex and sceptical man remains to me puzzling. It did not alleviate his pessimism — far from it. He seems to have been sceptical about scepticism itself, assuming that there are truths and beliefs beyond reason's reach. He regarded religion as more important than politics, perhaps hoped it was. History was for him meaningless without it. Reli- gion and hunger were for him the only really powerful motive forces in history (discuss: was Hitler religious or hungry?). He relied on religion alone (and not much on that) to prevent the destruction of society. Peguy declared that to value Christianity as a preservative of the social order was to insult it mortally. Sincere as he may have been in his own beliefs, Salisbury often comes perilously near to offering this insult. He is preserved from it by a gloomy consciousness that Christian- ity may destroy as well as preserve civilisa- tions, has destroyed two or three in its time, and will certainly destroy any civi- lisation which, formed under its auspices, subsequently rejects it. Kenneth Rose's readers will treasure many happy memories of Lady Gwen- dolen. They will find more gems in Hugh Cecil's affectionate memoir of her in the present volume. Her niece, Lady Harlech, found her reading in the garden on a very hot afternoon. On the table beside her lay her false teeth. 'I've taken them out,' she explained, 'one is so much cooler without them.' Unfair perhaps to list only the eccentricities of such a shrewd and percep- tive lady.

On the outbreak of the 1914 war, for instance, she wrote: I have a sneaking- pity for the Germans. }Lying made that fateful blunder in annex- ing [Alsace-Lorraine], there was no way out for them. The inevitable pressure of the growing half-barbarous Europe to East of them could have been faced alone — but not with the enduring enmity to West, & when they ask how they would be expected to wait

till the two were strong enough & for them to choose their own time for the attack, I don't feel I can answer them.

It took an exceptionally broad and de- tached mind to see things thus at that fraught moment, just as the Germans to her furious disgust were bomba'rding Lou- vain, 'the Oxford of the Low Countries'.

Lady Gwendolen, incidentally, was famous among numberless other charitable works for her sympathy for and generosity to local unmarried mothers. On Sundays she would have them in for a meal. She was unmarried and childless, though adored by her nephews and nieces. She might perhaps once have married the 15th Duke of Norfolk — photographs show her when young by no means unattractive — but, if nothing else, religion prevented her. Was there perhaps in her concern for unmarried mothers a touch of wistful unconscious envy for what had never been?

Previous page

Previous page