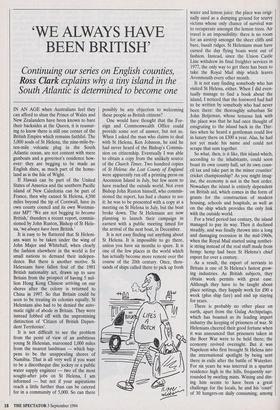

'WE ALWAYS HAVE BEEN BRITISH'

Continuing our series on English counties,

Ross Clark explains why a tiny island in the

South Atlantic is determined to become one

IN AN AGE when Australians feel they can afford to shun the Prince of Wales and New Zealanders have been known to bare their backsides at the Queen, it is reassur- ing to know there is still one corner of the British Empire which remains faithful. The 5,000 souls of St Helena, the nine-mile-by- ten-mile volcanic plug in the South Atlantic ocean, are not content with mere gunboats and a governor's residence how- ever: they are begging to be made an English shire, as much part of the home- land as is the Isle of Wight.

If Hawaii can be part of the United States of America and the southern Pacific island of New Caledonia can be part of France, then why cannot St Helena, 4,500 miles beyond the tip of Cornwall, have its own county council and its own Westmin- ster MP? 'We are not begging to become British,' thunders a recent report, commis- sioned by John Ruston, Bishop of St Hele- na, 'we always have been British.'

It is easy to be flattered that St Heleni- ans want to be taken under the wing of John Major and Whitehall, when clearly the fashion elsewhere in the world is for small nations to demand their indepen- dence. But there is another motive. St Helenians have fallen foul of the 1981 British nationality act, drawn up to save Britain from the prospect of having 5 mil- lion Hong Kong Chinese arriving on our shores after the colony is returned to China in 1997. So that Britain could be seen to be treating its colonies equally, St Helenians also had to be denied the auto- matic right of abode in Britain. They were instead fobbed off with the unpromising distinction of 'Citizen of British Depen- dent Territories'.

It is not difficult to see the problem from the point of view of an ambitious young St Hetertian, marooned 1,000 miles from the nearest landmass — which hap- pens to be the unappealing shores of Namibia. That is all very well if you want to be a discotheque disc jockey or a public water supply engineer — two of the most sought-after jobs on St Helena, I am informed — but not if your aspirations reach a little further than can be catered for in a community of 5,000. So can there possibly be any objection to welcoming these people as British citizens?

One would have thought that the For- eign and Commonwealth Office could provide some sort of answer, but not so. When I asked the man who claims to deal with St Helena, Ken Johnson, he said he had never heard of the Bishop's Commis- sion on citizenship. Eventually I was able to obtain a copy from the unlikely source of the Church Times. Two hundred copies of St Helena: the Lost County of England were apparently run off a printing press on Ascension Island in July, but few seem to have reached the outside world. Not even Bishop John Ruston himself, who commis- sioned the report, has had a chance to see it: he was to be presented with a copy at a meeting on St Helena in July, but the boat broke down. The St Helenians are now planning to launch their campaign in earnest with a public meeting timed for the arrival of the next boat, in December.

It is not easy finding out anything about St Helena. It is impossible to go there, unless you have six months to spare. It is one of the few places in the world which has actually become more remote over the course of the 20th century. Once, thou- sands of ships called there to pick up fresh water and lemon juice: the place was origi- nally used as a dumping ground for scurvy victims whose only chance of survival was to recuperate amongst the lemon trees. Air travel is an impossibility: there is no room for an airstrip amongst the sheer cliffs and bare, basalt ridges. St Helenians must have cursed the day flying boats went out of fashion. Instead, since the Union Castle Line withdrew its final freighter services in 1977, the only way to get there has been to take the Royal Mail ship which leaves Avonmouth every other month.

It is not easy finding somebody who has visited St Helena, either. When I did even- tually manage to find a book about the island, I noticed that the foreword had had to be written by somebody who had never been there: the thoroughly suburban Sir John Betjeman, whose tenuous link with the place was that he had once thought of emigrating to the island back in the Thir- ties when he heard a gentleman could live in luxury there on £300 a year. Alas, he had not yet made his name and could not scrape that sum together.

So what, then, is it like, this island which, according to the inhabitants, could soon boast its own county hall, set its own coun- cil tax and take part in the minor counties' cricket championship? As you might imag- ine, the economy is not in the best order. Nowadays the island is entirely dependent on British aid, which comes in the form of grants for the construction of modern housing, schools and hospitals, as well as on the ship which provides the only link with the outside world.

For a brief period last century, the island managed to pay its way. Then it declined steadily, and was finally thrown into a long and damaging recession in the mid-1960s, when the Royal Mail started using synthet- ic string instead of the real stuff made from hemp: hemp had been St Helena's chief export for over a century.

As a result, the export of servants to Britain is one of St Helena's fastest grow- ing industries. As British subjects, they obtain work permits with great ease. Although they have to be taught about place settings, they happily work for £90 a week (plus ship fare) and end up staying for years.

There is probably no other place on earth, apart from the Gulag Archipelago, which has boasted as its leading import industry the keeping of prisoners of war. St Helenians cheered their good fortune when it was announced that prisoners taken in the Boer War were to be held there; the economy revived overnight. But it was Napoleon who first brought St Helena into the international spotlight by being sent there in exile after the battle of Waterloo. For six years he was interred in a spartan residence high in the hills, frequently sur- rounded by swirling mists. Wining and din- ing him seems to have been a great challenge for the locals, he and his 'court' of 30 hangers-on daily consuming, among other rations, 75 lbs of beef, seven chick- ens, ten bottles of Bordeaux, two bottles of Graves, a bottle of champagne and a bottle of Madeira.

Drunkenness is not an uncommon vice on St Helena. Sailors used to call it 'the punch-house of the South Atlantic'. And by 'punch' they meant both senses of the word. Far from being a peaceful backwa- ter, Jamestown, the capital, and indeed the only town, echoed with the sound of fisticuffs until a succession of tyrannical governors began to treat itinerant sailors with the same rough-handed discipline they would have received in Portsmouth or Devonport.

As for the inhabitants, a good half of the present population is descended from slaves. Long after Britain abolished the slave trade in 1807, British ships were intercepting other slaving vessels in the mid-Atlantic and confiscating their cargos. The captured slaves were then 'freed' on St Helena, where instead of being slaves they became servants, with at least the the- oretical right to leave their labour. As they were 1,000 miles from the nearest land, very few chose to do so, and so their descendants remain to this day, many of them with delightful names such as Plato and Hercules.

Another group who inadvertently ended up on St Helena were Londoners made homeless in the Great Fire of 1666. Quite what they had done to deserve being trans- ported 5,000 miles from their former homes is difficult to guess, but whatever the reason, the East India Company felt it was doing them a favour. During this resettlement the island boomed. In 1676 the astronomer Edmund Halley came to build an observatory on St Helena, the island being the closest place to England where one could view the southern sky.

In 1834, with the British Empire about to enter its golden afternoon, control of St Helena passed from the East India Com- pany and the island became a crown colony. It is this move that St Helenians now say was an 'absent-minded mistake'. The island should never have been classi- fied as anything other than a fully-fledged part of Great Britain; it had been a fort and a staging-post for shipping, but never a proper colony. The only way to correct the mistake, claims the bishop's commis- sion, would be to declare it an ordinary English county forthwith.

If I were Douglas Hurd, constantly chal- lenged with making policy decisions relat- ing to dozens of new tin-pot nations around the world, each one claiming to have broken free from their old masters, I would jump at the chance. It is not often one gets the opportunity to annex territory at the request of the people who live there. Scotland, Wales and Ireland can do as they choose; I would rather be part of a union made up of willing peoples who know full well upon which side their bread is but- tered.

Previous page

Previous page