BOOKS

How did he get the job?

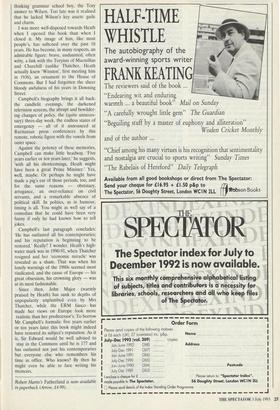

Robert Harris

EDWARD HEATH by John Campbell

Cape, £20, pp. 876

It is more than eight years since Edward Heath signed a contract and received a large advance from Lord Weidenfeld and the Sunday Times to write his memoirs. Various researchers have since picked their way through his immense archive (stored for a long time, curiously enough, in the basement of the Piccadilly Hotel), but nothing has happened. Given that Sir Edward is now 77, it is starting to look doubtful if anything ever will.

Why? His three picture books, Sailing (1975), Music (1976) and Travels (1977) sold more than 200,000 copies in hardback and earned him perhaps 000,000. Denis Healey made a small fortune out of his memoirs and Heath could reasonably expect to do the same. It is not, after all, as if money and the luxuries it buys are unimportant to him: on the contrary, he loves good wine, good food and the finer things of life. The attendant interviews, speeches and signings would give him nothing but pleasure. Yet the years pass, Lord Weidenfeld's accountants rub their hands uneasily, and no word appears.

Conventionally, politicians do not write their memoirs if they nurse hopes of a comeback. But surely even Heath — who dreamed of a return throughout the 1980s and who has still not installed his commemorative window in Chequers — even Heath must have abandoned that fantasy by now. So we are left with only one plausible explanation for his silence: he cannot bear to face the extent of his failure. Or, as John Campbell more politely puts it:

Much of what he is required to relive sits uneasily with his view of the past as he has refashioned it in his mind since 1974 . . . it is disconcerting to be faced by his assistants with speeches he would prefer to believe he had never made. It is easier to justify himself in general than in detail.

Mr Campbell struggles heroically to tie together all the contradictory strands of Heath's life — the smiling mummy's boy, the brisk army colonel, the charming chief whip, the charmless leader, the free- marketeer, the corporatist, 'the Grocer', the visionary, the Little Englander, the European, the sensitive aesthete, the rude boor — and if, at the end, he doesn't quite manage to fashion a coherent psychological whole, the attempt is honest, honourable and compelling.

It is tempting to see this massive book as a companion volume to Ben Pimlott's equally massive revisionist study of Harold Wilson, published last year. But whereas there is a strong revisionist case to be made for Wilson, and Pimlott argued it powerful- ly, Heath's premiership ended in such disaster that Campbell, although fair and generous throughout, wisely eschews advocacy.

Ever since the mid-1960s, Heath seems to have had a genius for getting it wrong, from town planning CI want to see the guts torn out of our older industrial cities and new civil centres and shopping areas built there') to the creation of 'super ministries'.

'Click. beeep . . . I'm sorry I'm out . . . please leave your. .

He clung to the idea of a post-imperial role east of Suez. He supported the saturation bombing of North Vietnam. He antagonised the unions with the Industrial Relations Act, then called on them to be patriotic, and wondered why they laughed in his face. He stoked an unsustainable economic boom and sowed hyper-inflation. He came to office pledged to reduce the size of government, and left it with 400,000 more employees. He wanted to extend the free market, yet introduced the Industry Act, giving Whitehall more powers of inter- vention than any socialist administration had ever dreamed of. He let Keith Joseph 'reform' the NHS, with disastrous results. He introduced internment in Northern Ireland, against the wishes of the Army, and played into the hands of the IRA. He sucked up to the Chinese communists (declaring Mao to have 'a delightful sense of humour') and went on doing it, even after the massacre in Tiananmen Square. He predicted ruin for the allies in the Gulf War. He underrated the significance of Mikhail Gorbachev.

Of course, all statesmen and commenta- tors make misjudgments and are mocked by events. But Heath seems to have been peculiarly inept even at the basic require- ments of his chosen trade. Hopeless on television, worse on a public platform, charmless in most social situations, 'he lacked,' in Campbell's words,

the essential quality of political leadership: the ability to communicate his vision and inspire loyalty beyond the narrow circle of his closest colleagues.

He fought four elections; he lost three. He might have retained the Tory leadership if he had submitted himself for re-election swiftly, in the autumn of 1974, but he didn't; he could certainly have prevented the Thatcherite takeover by standing down six months later in favour of Whitelaw, but he didn't. He could have been Foreign Secretary in 1979 if he had deigned to treat his successor politely; he might even have destroyed her with a devastating resignation in the early 1980s. But it all went for nothing. He was just very bad at politics.

The question is how he ever managed to become leader in the first place. Campbell answers it by wittily comparing his ascent to Stalin's. He was the Chief Whip with the card index system, the fixer who never opened his mouth, the mechanic of the party machine. His more glamorous rivals — Maudling, Macleod, Hailsham — all destroyed themselves, and so the field was left to Ted: the hard-working, modern- thinking grammar school boy, the Tory answer to Wilson. Too late was it realised that he lacked Wilson's key assets: guile and charm.

I was more well-disposed towards Heath when I opened this book than when I closed it. My image of him, like most people's, has softened over the past 18 years. He has become, in many respects, an admirable figure: brave, undaunted, often witty, a link with the Toryism of Macmillan and Churchill (unlike Thatcher, Heath actually knew 'Winston', first meeting him in 1936), an ornament to the House of Commons. But I had forgotten the sheer bloody awfulness of his years in Downing Street.

Campbell's biography brings it all back: the candlelit evenings, the darkened television screens, the abrupt and bewilder- ing changes of policy, the (quite unneces- sary) three-day week, the endless states of emergency — all of it announced at Ruritanian press conferences by this remote, robotic figure with the vowels from outer space.

Against the potency of these memories, Campbell can make little headway. 'Five years earlier or ten years later,' he suggests, 'with all his shortcomings, Heath might have been a great Prime Minister.' Yes, well, maybe. Or perhaps he might have made a pig's ear of those periods, too, and for the same reasons — obstinacy, arrogance, an over-reliance on civil servants, and a remarkable absence of political skill. In politics, as in humour, timing is all. You might as well say of a comedian that he could have been very funny if only he had known how to tell jokes.

Campbell's last paragraph concludes: 'He has outlasted all his contemporaries; and his reputation is beginning to be restored.' Really? I wonder. Heath's high- water mark was in 1990-91, when Thatcher resigned and her 'economic miracle' was revealed as a sham. That was when his lonely warnings of the 1980s seemed most vindicated, and the cause of Europe — his great obsession, his crowning glory — was at its most fashionable.

Since then, John Major (warmly praised by Heath) has sunk to depths of unpopularity unplumbed even by Mrs Thatcher, while the ERM fiasco has made her views on Europe look more realistic than her predecessor's. To borrow Mr Campbell's formula: five years earlier or ten years later this book might indeed have restored its subject's reputation. As it is, Sir Edward would be well advised to stay in the Commons until he is 177 and has outlasted not just his contemporaries but everyone else who remembers his time in office. Who knows? By then he might even be able to face writing his memoirs.

Robert Harris's Fatherland is now available in paperback (Arrow, £4.99).

Previous page

Previous page