Decimalisation: A U.K. Dollar

By NICHOLAS DAVENPORT THE most irritating point, you will remember, about the report of the Halsbury Committee on decimalisa- tion was that after nearly two years' rumination they could not agree. Four of them plumped for the £-

cent-f cent system and two for the 10s.-cent system and by publishing their disagreements they did their best to kill decimalisation for all time. And the sickening feature of the majority report was that they fell for all the mystique about the £ conjured up by the Bank of England, Sir Geoff- rey Crowther and the financial mandarins of the City. It was therefore heartening to read in The Statist at Christmas a realistic article by a well- known American economist, Dr. Sidney Rolfe, late of Princeton and Columbia, telling them where they all went wrong and putting forward a far better plan.

The so-called 'international case' for the £-cent-1 cent, as opposed to the 10s.-cent system which South Africa adopted and Australia and New Zealand intend, is based on the notion that the £ is part of the external image of the City of London and that tampering with it would be to run the risk of damaging the business of the City, which, they say, earns about £150 million in a good year. The Bank of England went so far as to declare that this argument was crucial —that it was not a matter of sentiment, but of livelihood. Crowther shamelessly tried to frighten the Committee by saying: 'It would be felt that if the British were now willing to alter the

value of the for one reason they might be willing enough to do it in another way for other (and perhaps more pressing) reasons'—as if deci- malisation implied devaluation. Even sillier was the argument of the British Insurance Associa- tion that 'the idea of the £ sterling was inex- tricably bound up in the minds of many foreigners, particularly in some Middle Eastern countries where a great deal of British insurance business originated, with the idea of London as solid, secure, and financially trustworthy.' Per- haps the Arab boycott committee had told them that decimalisation was really a Jewish plot. The prestige of London as a world financial centre rests, of course, on the unique facilities it offers within its one square mile for an international trader to fix up finance, insurance and shipping on signing little pieces of paper which are always honoured. As the minority report said: 'We be- lieve that the City does itself less than justice by suggesting that a large section of foreign cus- tomers might take their business elsewhere as the result [of decimalisation] and so deprive them- selves of the continued enjoyment of the in- tegrity and unrivalled services and experience which the City gives.' Incidentally, the Committee never even asked the foreign customers their opinion. The Bank of England advised them not to do so Now comes Dr. Sidney Rolfe breathing some refreshing common sense into these arid disputes. Keep the £ as the heavy unit of account, he says, and create a new smaller unit—the British dollar, currently valued at what the American dollar is worth today, namely, 7s. 2d., divided as usual into one hundred cents. This would meet better than any other system the criteria laid down in the Halsbury Committee report and would avoid most of the pitfalls of the plan recommended by the majority. It would cer- tainly provide a consistent and unbroken decimal system which the f-cent-/ cent system does not. The units of the new British dollar would be small and viable (the cent being 0.86d.)—unlike the unit of the Halsbury plan whose half-cent would be equivalent to 1.2d., which is too large for comfort or convenience. (Everything quoted in +d. would surely be rounded upwards to 1.2d.) And a feature of the Rolfe plan which 1 find attractive is that the units of the new British dollar would have no `associability' with the existing coins of our present system. It would be possible to use the half-crown, being equiva- lent to thirty-five cents, but it would be better to start with entirely new coins for one cent, five cents, ten cents, twenty-five cents and fifty cents. The less these new coins could be associated with present coins, the less confusing the change would be. The psychological tests showed that it was easier for a housewife to work in a decimal coinage for her household accounts than in £ s. d. Domestically I believe the British dollar would grow to be popular. The word dollar is already used in English slang and you will find it in Shakespeare.* Externally the Rolfe plan should please the foreigner, the City of London and even the British Insurance Association. The £ would be kept for all international transactions conducted in sterling and would probably retain its popu- larity, being a heavier international unit than the American dollar. Five pounds would be exactly equivalent to fourteen new British dollars. The £ would continue to move in the exchanges within its existing limits exactly as it does today and I see no reason why any foreigner should doubt its new status. With the new British dollar on a par with the American dollar, external confidence in our currency would surely be strengthened rather than diminished. Before long the foreigner would be saying: told you so : the American and British reserve currencies stand or fall to- gether. They are indissolubly linked together.' That is exactly what Sir George Bolton, a direc- tor of the Bank of England, chairman of the Bank of London and South America and our greatest expert on foreign exchange, has been preaching for months and months.

At the end of his article Dr. Rolfe makes a confession of his faith in Anglo-American co- operation, economic and financial. He thinks that the adoption of what amounts to a common in- ternal currency would provide the American and British economies with a common measuring rod for movements in industrial costs and prices which is not available today at factory level. Seeing that the Americans are far ahead of us in management skills and production techniques, this could be extremely useful. I agree with him that a currency reform of this kind would not only have some political significance, proclaim- ing that there is, as de Gaulle says, an Anglo- American axis, but would be a constructive move, bringing the two reserve currencies closer to- gether and linked for the final attack which we Anglo-Saxons must make on the antiquated monetary system that is hampering world trade.

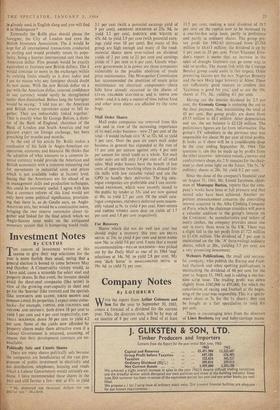

Previous page

Previous page