Chasing Getty’s ‘Youth’

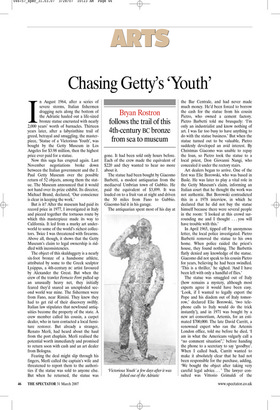

Bryan Rostron follows the trail of this 4th-century BC bronze from sea to museum In August 1964, after a series of severe storms, Italian fishermen dragging nets along the bottom of the Adriatic hauled out a life-sized bronze statue encrusted with nearly 2,000 years’ worth of barnacles. Thirteen years later, after a labyrinthine trail of greed, betrayal and smuggling, the masterpiece, ‘Statue of a Victorious Youth’, was bought by the Getty Museum in Los Angeles for $3.98 million, then the highest price ever paid for a statue.

Now this saga has erupted again. Last November negotiations broke down between the Italian government and the J. Paul Getty Museum over the possible return of 52 objects, among them the statue. The Museum announced that it would not hand over its prize exhibit. Its director, Michael Brand, declared, ‘Our conscience is clear in keeping the work.’ But is it? After the museum had paid its record price in 1977, I investigated in Italy and pieced together the tortuous route by which this masterpiece made its way to California. It led from a murky art underworld to some of the world’s richest collectors. Twice I was threatened with firearms. Above all, though, it shows that the Getty Museum’s claim to legal ownership is riddled with inconsistencies.

The object of this skulduggery is a nearly six-foot bronze of a handsome athlete, attributed by some to the Greek sculptor Lysippus, a 4th-century BC artist favoured by Alexander the Great. But when the crew of the trawler Ferrucio Ferri pulled up an unusually heavy net, they initially feared they’d snared an unexploded second world war mine. The fishermen were from Fano, near Rimini. They knew they had to get rid of their discovery swiftly. Italian law stipulates that newfound antiquities become the property of the state. A crew member called his cousin, a carpet dealer, who in turn contacted a local furniture restorer. But already a stranger, Renato Merli, had heard about the haul from the port chaplain. Merli realised the potential worth immediately and promised to return soon with cash and an art dealer from Bologna.

Fearing the deal might slip through his fingers, Merli called the captain’s wife and threatened to report them to the authorities if the statue was sold to anyone else. But when he returned, the statue was gone. It had been sold only hours before. Each of the crew made the equivalent of $220 and they wanted to hear no more about it.

The statue had been bought by Giacomo Barbetti, a modest antiquarian from the mediaeval Umbrian town of Gubbio. He paid the equivalent of $3,899. It was loaded on to a fruit van at night and driven the 50 miles from Fano to Gubbio. Giacomo hid it in his garage.

The antiquarian spent most of his day at the Bar Centrale, and had never made much money. He’d been forced to borrow the cash for the statue from his cousin Pietro, who owned a cement factory. Pietro Barbetti told me brusquely: ‘I’m only an industrialist and know nothing of art. I was far too busy to have anything to do with the statue business.’ But when the statue turned out to be valuable, Pietro suddenly developed an avid interest. By Christmas Giacomo was unable to repay the loan, so Pietro took the statue to a local priest, Don Giovanni Nangi, who concealed it under the rectory stairs.

Art dealers began to arrive. One of the first was Elie Borowski, who was based in Basle. He was later to play a vital role in the Getty Museum’s claim, informing an Italian court that he thought the work was not authentic. But Borowski contradicted this in a 1978 interview, in which he declared that he did not buy the statue himself because there were several people in the room: ‘I looked at this crowd surrounding me and I thought ... you will have trouble with this.’ In April 1965, tipped off by anonymous letter, the local police investigated. Pietro Barbetti removed the statue to his own home. When police raided the priest’s house, they found nothing. The Barbettis flatly denied any knowledge of the statue. Giacomo did not speak to his cousin Pietro for years, believing he had been swindled. ‘This is a thriller,’ he sighed. ‘And I have been left with only a handful of flies.’ The statue was smuggled out of Italy (how remains a mystery, although most experts agree it would have been easy. ‘Look, if I wanted to legally export the Pope and his diadem out of Italy tomorrow,’ declared Elie Borowski, ‘two telephone calls to Italy would do the trick instantly’), and in 1971 was bought by a new art consortium, Artemis, for an estimated $700,000. The late David Carritt, a renowned expert who ran the Artemis London office, told me before he died, ‘I am in what the Americans vulgarly call a “no comment situation”,’ before handing the phone to a secretary to say ‘goodbye’. When I called back, Carritt wanted to make it absolutely clear that he had not been responsible for the purchase, adding, ‘We bought the object after taking very careful legal advice... ’ The lawyer consulted was Vittorio Grimaldi of the influential Rome firm of Graziadei. He had not given advice on the ‘export’ from Italy but on the legality of the purchase.

The statue was shipped to Munich for restoration, which took some time, then offered to European and American museums. Various potential customers dropped out over the years, due to doubts about the legal title. The main suitor, the oil baron J. Paul Getty, who had been advised by Elie Borowski to buy it but not to pay more than $2 million, was not satisfied either that Artemis had legal title, and it was not until a year after his death, in November 1977, that the Museum trustees finally paid the record price of $3.98 million. But was this sale legal?

Recently Michael Brand wrote that the statue had been found in international waters (possible, but not proved), and that it ‘was obtained by the Museum in 1977 only after Italian courts had declared that there was no evidence that it belonged to Italy’.

These court cases, however, revolved round an audacious lie. The first trial against the Barbettis was in 1966. Their defence was that the statue had been found in international waters and that it was of no worth. A letter from Elie Borowksi informed the court that the statue was not an original and was possibly a Roman copy. The case was dismissed on account of ‘lack of proof’.

The prosecution appealed and in 1967 a Perugia court concluded that the statue had been of value and the defendants were given suspended sentences. This time the Barbettis appealed and in 1968 the case came before a higher Rome court. The Barbettis were represented by one of Italy’s top lawyers, whose defence was simple: the statue had never been produced. The Court of Cassation, which does not pass sentence but establishes legal principle, sent the case to the Rome Appeal Court with the strong recommendation that all sentences be quashed, ‘as the statue has not been presented, and therefore due to the impossibility of establishing if it was of artistic, historic or archaeological interest or had been dug up or found by chance’. In 1970, the Rome Appeal Court ruled that, owing to lack of proof, it was impossible to establish where the statue had come from or if it was of any value. As one Italian lawyer chuckled, ‘An elephant was disguised as a mouse.’ This imbroglio is aggravated by the ongoing trial in Rome of a former Getty curator, Marion True, who is charged with buying stolen Italian antiquities — terrible timing, perhaps, for the Getty Museum to stake its claim to that contested statue, for which it paid a record price, on a judgment that concluded it could not be proved to be of any worth at all. This beautiful bronze youth may now be cleansed of sea encrustations, but he’s still thoroughly shrouded in artful intrigue.

Previous page

Previous page