Exhibitions 2

Builder of Towers: William Beckford and Lansdown Tower (Christie's, 8 King Street, until 3 February)

Wayward child of fortune

Ruth Guilding

Some people drink to forget their unhappiness. I do not drink — I build.' William Beckford, the reclusive millionaire who inherited his millions at the age of nine, devoted his long life to works which amply justified this remark. Of the monu- ments created during his life, however, lit- tle has survived intact: one collapsed tower remains of the great Gothic abbey of Fonthill, his libraries and precious objects are dispersed throughout museums and private collections worldwide and the prop- erties and gardens which he pieced togeth- er in Bath have been broken up and developed. The secret of the great 'unhap- piness', which fuelled Beckford's compul- sion, has been decently cloaked beneath the respectful mantles of architectural criti- cism, literary biography and art history.

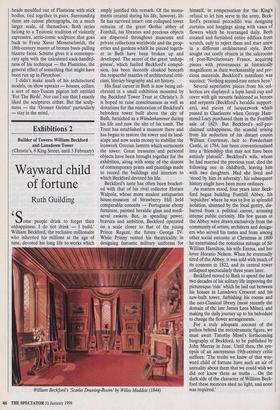

His final career in Bath is now being cel- ebrated in a small exhibition mounted by the Beckford Tower Trust at Christie's. It is hoped to raise consciousness as well as donations for the restoration of Beckford's belvedere tower built above the city of Bath, furnished as a Wiinderlcammer during his life and now the site of his tomb. The Trust has established a museum there and has begun to restore the tower and its land- scape and now seeks money to stabilise the ironwork Grecian lantern which surmounts the tower. Great treasures and personal objects have been brought together for the exhibition, along with some of the dozens of contemporary prints and paintings made to record the buildings and interiors to which Beckford devoted his life.

Beckford's taste has often been bracket- ed with that of his rival collector Horace Walpole, whose more modest antiquarian house-museum of Strawberry Hill held comparable conceits — Portuguese ebony furniture, painted heraldic glass and medi- aeval caskets. But, in spending power, bravura and ambition, Beckford operated on a scale closer to that of the young Prince Regent, the future George IV. While Primly vented his theatricality in designing fantastic military uniforms for William Beckford's 'Scarlet Drawing-Room' by Willes Maddox (1844) himself, in compensation for the King's refusal to let him serve in the army, Beck- ford's personal peccadillo was designing curtains and hangings along with vases of flowers which he rearranged daily. Both created and furnished entire edifices from scratch, only to reject them and start anew in a different architectural style. Both sought out costly objects in the salerooms of post-Revolutionary France, acquiring pieces with provenances as historically magnificent as their workmanship and pre- cious materials. Beckford's manifesto was succinct: 'Nothing second-rate enters here.'

Several superlative pieces from his col- lection are displayed: a lapis lazuli cup and cover with gilt mounts fashioned as herons and serpents (Beckford's heraldic support- ers), and pieces of lacquerwork which passed to Charlecote when George Ham- mond Lucy purchased them in the Fonthill sale of 1823. But Beckford's self-pro- claimed unhappiness, the scandal arising from his seduction of his distant cousin William Courtenay, heir to Powderham Castle, in 1784, has been conventionalised into a 'friendship that may not have been entirely platonic'. Beckford's wife, whom he had married the previous year, died the following one in childbirth, leaving him with two daughters. Had she lived and 'stood by him in adversity', his subsequent history might have been more ordinary.

As matters stood, four years later Beck- ford began building Fonthill Abbey, his 'sepulchre' where he was to live in splendid isolation, shunned by the local gentry, dis- barred from a political career, arousing intense public curiosity. His few guests at the Abbey were drawn exclusively from the community of artists, architects and design- ers who served his tastes and from among other social outcasts: at Christmas in 1800 he entertained the notorious ménage of Sir William Hamilton, his wife Emma, and her lover Horatio Nelson. When he eventually tired of the Abbey, it was sold with much of its contents in 1822, and its central tower collapsed spectacularly three years later.

Beckford moved to Bath to spend the last two decades of his solitary life improving the picturesque 'ride' which he laid out between his houses in Lansdown Crescent and his new-built tower, furbishing his rooms and the neo-Classical library (most recently the domain of the late James Lees Milne), and making the daily journey up to his belvedere to change the flower arrangements.

For a truly adequate account of the pathos behind the melodramatic figure, we must await Timothy Mowl's forthcoming biography of Beckford, to be published by John Murray in June. Until then, the syn- opsis of an anonymous 19th-century critic suffices: 'The truths we know of that way- ward child of fortune have such an air of unreality about them that we could wish we did not know them as truths. On the dark side of the character of William Beek- ford these memoirs shed no light, and none was required.'

Previous page

Previous page