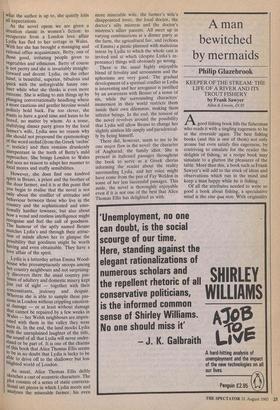

A man bewitched by mermaids

Philip Glazebrook

KEEPER OF THE STREAM: THE LIFE OF A RIVER AND ITS TROUT FISHERY by Frank Sawyer

Allen & Unwin, £9.95

Agood fishing book fills the fisherman who reads it with a tingling eagerness to be at the riverside again. The best fishing books (and this is one of them) not only arouse but even satisfy this eagerness, by contriving to simulate for the reader the delights of fishing, as a recipe book may simulate to a glutton the pleasures of the table. More than this, a book such as Frank Sawyer's will add to the stock of ideas and observations which run in the mind and keep a man happy while he is fishing.

Of all the attributes needed to write so good a book about fishing, a speculative mind is the sine qua non. With originality and freshness Sawyer wonders about the natural world. Why will trout sometimes take the artificial fly so greedily in the mayfly season, and sometimes refuse it? With the question in his mind, Sawyer watches with patience and observes with exactness, his head under water if need be. Then he makes his deduction. Is it that there are times, during a hatch of fly, when weather or temperature prevent the female laying her eggs on the river and drifting down its current dead, in which case the trout expect, and eat, only the fluttering live fly as it emerges from its nymph-case and dries its wings before flying into the air? If conditions change, and the dead females fall in quantities upon the water, then will the trout take the lifeless artifi- cials they mistake for them? He may be right or wrong, but he has carried us with him to the chalk stream on stormy and still June evenings to share his observations; and we will carry him with us, testing his ideas, reflecting on his insights, beside the river on future summer days.

His enquiries would not stay in the memory, however, had he not developed a perfectly lucid prose style to express them, rare accomplishment in a fisherman, espe- cially in a dry-fly man. Too often Surtees' Pomponius Ego begat the fishing writer — Eftsoons brimmed my creel with the spot- ted beauties of unblushful Hippocrene' — who obliges us to wade through seas of treacle to get at the point. Sawyer writes extremely well. Clear in the exposition of technicalities, his style is allowed the touch of lyricism which is needed where a love of wild life is to be conveyed and vigorous or pathetic images of the natural world put into the reader's mind. Sawyer's account of a flood well displays his power as a writer in ranging between its wide views of general inundation and its particular vig- nettes of mole or shrew facing catastrophe. It is notable that his metaphors, by refer- ring the reader's mind only to other natural scenes — a rise of trout, for instance, he compares to 'a flock of lambs in a field of clover' — keep the reader within the author's own boundaries, and give a unity of outlook to the book. Such an open-air book about chalk- stream fishing is uncommon, for it is a bookish sport with a history of literary polemics. But Sawyer mentions only one book, a work of Skues. He relied entirely on his own observations and deductions. Once he begins 'According to scientists' but soon returns to the surer ground of `Pondering this' or 'I have given much thought to the matter'. Here lies the originality of the book over, say, J. W. Hills' life of the Stockbridge keeper, Lunn, in which the spontaneity of the river- keeper is filtered through Hills' wider reading and greater sophistication. And here, too, in this independence, lies the weakness of some of Sawyer's theorising, for he is not aware, it seems, that his questions (on the origin of dry-fly fishing for instance) may be satisfactorily answered by reference to fishing's vast literature. Not that he is opinionated: one of the charms of the book is that he is ready to write 'For some natural reason of which I had no knowledge' as the preface to a description (of toads).

Though we learn little about him directly from the book, he lets drop one or two hints as to his inner self. 'The most insignificant of river life [he writes] has a coloration and symmetry that far surpasses anything that lives in the open air.' Here is a man bewitched by mermaids. No doubt he developed the fishing of the underwater nymph as a magic casement opening into that underwater kingdom towards which he seems to have longed, for in that 'most fascinating' of sports the angler in a chalk stream sees every movement of trout and fly with a closeness and clarity which draws him down under the surface of the stream as no other form of fishing does.

Of his terrestrial self away from the river we hear almost nothing. He is discreet, even distant, in the proper tradition of keepers and stalkers and ghillies towards `rod' or 'rifle' or 'gun' whom they ostens- ibly serve. Although as carefully polite towards 'gentlemen' as he is towards the opinions of scientists, Sawyer expects little good of them. 'I have spent whole days with fishermen [he says], seeing them rise and miss fish after fish, and put down many others they might have risen had they exercised a little more control over their emotions.' The tone has the affectionate contempt of a member of the Junior Ganymede for a member of the Drones.

I might have felt a proper object of such contempt beside Sawyer on the Avon, but I read his book with pure delight. A boy at school kept from his passion for the river, or an old man past fishing, may feel the rod spring again in his hand as he reads, and whoever has walked by running water will hear again in this book its glorious clear elapse which filters all cares from the mind. There are not many books which will achieve so much, and when a classic such as this reappears, it should be bought at once.

Previous page

Previous page