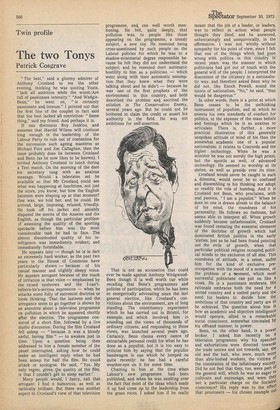

The two Tonys

Patrick Cosgrave

"The best," said a gloomy admirer of Anthony Crosland to me the other evening, thinking he was quoting Yeats, "lack all ambition while the worst/Are full of passionate intensity." "And WedgieBenn," he went on, "is certainly passionate and, intense." I pointed out that the first line of the couplet in fact said that the best lacked all conviction: "Same thing," said my friend. And perhaps it is.

If one discounts Roy Jenkins, and assumes that Harold Wilson will continue long enough in the leadership of the Labour Party to rule out of contention for the succession such ageing maestros as Michael Foot and Jim Callaghan, then the issue probably does lie between Crosland and Benn (as he now likes to be known). I invited Anthony Crosland to lunch during a Test match. On the morning of the date his secretary rang with an anxious message. Would a television set be available so that Mr Crosland could see what was happening at lunchtime, not just the score, you know, but how the English batsmen were shaping up at that moment? One was, we told her, and he could. He arrived, large, imposing, relaxed, friendly. He took off his jacket and amiably disputed the merits of the Aussies and the English, as though the particular problem assessing the quality of the sporting spectacle before him was the most considerable task he had to face. The almost disembodied quality of his intelligence was immediately evident; and immediately formidable.

He appears lazy — though he is in fact an extremely hard worker, as the past two years in the House of Commons have particularly shown — because of his casual manner and slightly sleepy voice. He appears arrogant because of the touch of irritation in that voice — emphasised by the raised eyebrows and the I-can'tbelieve-he's-serious expression — when he attacks some folly of extremist doctrine or loose thinking. That the laziness and the arrogance seem to go together is shown by an anecdote about a television programme on pollution in which he appeared shortly after the election. The programme consisted of a short film, followed by a live studio discussion. During the film Crosland fell asleep — "because it was a bloody awful, boring film" — to awaken just in time. Upon a question being then addressed to him a female member of the panel interrupted, asking how he could make an intelligent reply when he had been asleep for half the film. He could attack or apologise. He said, "Yes. My only regret, given che quality of the film, is that I couldn't get to sleep earlier."

Many people would, I fancy, call that arrogant: I find it humorous, as well as tactically brilliant. But there was another aspect to Crosland's view of that television programme, and one well worth mentioning. He felt, quite deeply, that pollution was, to people like those appearing on the programme, a trendy subject, a new toy. He resented being cross-questioned by such people on the Labour policies for which he was to a shadow-ministerial degree responsible because he felt they did not understand the subject; and he resented their automatic hostility to him as a politician — which went along with their automatic assumption that they knew what they were talking about and he didn't — because he was one of the first prophets of the environment in this country, and both described the problem and ascribed the solution in The Conservative Enemy, several years ago. But he could not be bothered to claim the credit or assert his authority in the field. He was not ambitious for self-assertion.

That is not an accusation that could ever be made against Anthony WedgwoodBenn though it is well worth our while recalling that Benn's programmes and policies of participation, which he has been so energetically advocating since the last general election, like Crosland's convictions about the environment, are of long standing. The constituency experiment which he has carried out in Bristol, for example, and which involved him in sounding out the views of thousands of ,ordinary citizens, and responding to those views, was launched several years ago. Certainly, Benn claims every ounce of extractable personal credit for what he has done as a populist; but it is too easy to criticise him by saying that the populist bandwagon is one which he jumped on quite recently: he has had a careful weather-eye on it for some time.

Chatting to him at the time when Labour's new programme had been published, and when he was exulting over the fact that most of the ideas which made it up had come up to the leadership from the grass roots, I asked him if he really meant that the job of a leader, or leaders, was to reflect in action what people thought they liked, and he answered, unhesitatingly and unequivocally, in the affirmative. I was not wholly without sympathy for his point of view, since I felt that one of the things which had gone wrong with politics in this country in recent years was the manner in which politicians had got out of touch with the general will of the people. I interpreted the discontent of the citizenry in a nationalistic way, and therefore asked Benn why he did not, like Enoch Powell, sound the tocsin of nationalism. "No," he said, "that would be dangerous."

In other words, there is a point at which Benn ceases to be the unthinking instrument of populism, and at which he asserts his own standards of conduct for politics, at the expense of the mass beliefs and feelings which he is so anxious to articulate. There is, further, a more practical illustration of this generally unspoken attitude of mind of his than the somewhat academic one of a popular nationalism: it relates to Concorde and the higher technology. When he was a minister he was not merely the high priest, but the apostle as well, of advanced technology. He seemed to worship at its shrine, as well as preside over its rites.

Crosland would never be caught in such a dilemma, would never be so confused and dissembling in his thinking nor adopt so readily the role of humbug. And it is Crosland not Benn, who proclaims, with real passion, "I am a populist." When he does so one is drawn afresh to the balance of his mind, the roundness of his personality. He follows no fashions, but seems able to interpret all. When growth suddenly became unfashionable, Crosland was found restating the essential elements of the doctrine of growth which had dominated British politics in -the early 'sixties, just as he had been found pointing out the evils of growth, when that particular political religion occupied political minds to the exclusion of all else. This roundness of attitude, in a sense, unfits him for the kind of exclusive preoccupation with the mood of a moment, or the problem of a /moment, which most successful politicians can put on like a cloak. He is a passionate moderate. His rationale embraces both the need for a united country and a united party and the need for leaders to decide how the ambitions of that country and party are to be achieved. The question about him is how an academic and objective intelligence would operate, allied to a remarkable social conscience, somewhat concealed bY his offhand manner, in power.

Benn, on the other hand, is a power broker. I asked him recently on a television programme why his speeches and exhortations were directed towards the trade unions and not towards, say, the old and the halt, who were, much more than able-bodied workers, the victims of the constraints of the inflationary societY. Did he not feel that they, too, were part of the general will, which he was so eager to .cultivate and encourage; and were theY not a particular charge on the Socialist, conscience? His reply was to the effect that pensioners — his chosen example out

Of the whole constituency of the vulnerable — represented a substantial portion of the electorate; and if they organised themselves they, like the Upper Clyde shipping workers, or the trades unions generally, could be a powerful political force. He was not, it seemed to me, willing to take up their cause until they had shown their muscle. Vulnerability and need, I thought, did not dictate his preference of allies: proven power did.

And he is immensely acute at detecting evidence of power. Far from being, in his analysis of the political situation, a man Who detects the general will and acts upon it, he is perhaps the first senior politician Who has seen the capacity of the organised minority to disrupt, and by disruption to make its will felt. I am not saying that his Chosen minorities — whether the ship builders of Upper Clyde, or the dockers of London — are necessarily wrong in their stands against government; but I am suggesting that the rightness or wrongness of their causes has little to do with Benn's SUpport of them. He is interested in their Power, and cultivates it. Thus, for all his expressed and avowed populism, he has an essentially 'fifties view of politics; a Niiew Which suggests that it is the business of government to negotiate between power blocs and harmonise their interests, not to decide between policies and act on those decisions, in the service of the national interest as a whole.

Crosland, I think, adopts an almost exactly opposite philosophy. Few politi cians understand better than he the strangled wishes, impulses and needs of People. But he puts himself forward, not as a reflector of those wishes, needs and Impulses, but as one who understands how Political power can be used, by a government, to satisfy them. And yet — there is a beautifully harmonic irony here -it is Benn, the power broker, and not Crosland, the man who knows how to use Power, who is intensely ambitious.

Ambition is evident in every look and Move of Anthony Wedgwood-Benn. The Sharpness, keenness and alacrity of his Inovements, the quickness of his eye, suggest it. Crosland, like a large number of Politicians today, in spite of Muggeridge's dicta, is reluctant to contemplate the Personal cost of assuming power. When he realised after Jim Callaghan had resigned from the Treasury that the choice of a s, ucceasor as Chancellor lay betweed himself and Roy Jenkins he was, to a degree, horrified. He saw the tolls very high office might exact from his private `if e. He is a serious and dedicated Politician, of course, but he is an exceptionally human one, and, when he saw the opportunity of the second

lost powerful office in government coming his way, he looked at his wife and felt that he chalice ought to pass. It did. It may be that there is a law of Politics here which dictates that only those who want something intensely will ever get it. And if that law does operate n, °thing could be surer than that Benn will ,Iorie comfortably home in any race for the

Labour leadership in which his opponent is Crosland. And yet — here again the irony Crosland is a man who wants to use such power as comes his way; Benn, I feel, is a man who wants to enjoy it.

"Power," Churchill once wrote, "for the sake of lording it over fellow-creatures or adding to personal pomp, is rightly judged base. But power in a national crisis, when a man believes he knows what orders should be given is a blessing." The distinction is a nicer one than may appear from Churchill's bold prose, but it is real nonetheless. In the imperfect system which is modern British democracy a man can be elected only if the citizenry believe he will follow their interests, interpret them accurately, and act upon them. But once in power he may lose his sense of direction; in which case the only sanction against him is dismissal: there is no known way of exercising supervision over a government or Prime Minister, for democratic politics in a large state is a matter of trust. What cannot, I think, be disputed is that the elected leader or leaders in such a system, while they must both mirror and act, must act rather than mirror.

In assessing how a man will act, and whether he will act wisely or not, his intelligence is a better guide than his ambition. Both Crosland and Benn are men of great ability; they possess considerable skills. But Crosland cultivates understanding, while Benn cultivates apprehension. Crosland is inclined to say, this is how it should be done, for the following reasons. Benn is inclined to look a particular section of the electorate over, appraise its strength, and say, what do you want to be done? He is always beavering, while Crosland is often considering. There is a story that when Harold Lever, a man very like Crosland in some respects, became one of Benn's subordinate ministers, he was summoned to a breakfast time conference at his chief's office. "What," inquired the horrified Lever, "do we do about breakfast?" He was told that a sandwich would be available; and he went out and ordered a Fortnum and Mason hamper to be delivered to the site of the meeting. That action, like Crosland's on the television programme I mentioned earlier, was humorous; it was also sensible. There was no earthly reason why the two ministers had to meet before they had eaten. The extra time thus made available to them did not increase their capacity to take the right decisions: it merely emphasised a style of doing things, a humourless, intense, energetic style; but not necessarily a wise or fruitful one.

It is a style which encapsulates a certain attitude to modern government. The philosophy behind that attitude suggests energy as the be-all and end-all of political activity, energy to discover what the constituency wants, energy in pursuit of the constituencies wishes, as though energy, rather than thought or introspection, was the essential good. Yet, without thought, energy is ultimately purposeless. And, as one watches Benn in ceaseless pursuit of his objectives one feels that he rarely stops to brood, if he does so at all. Thus, even if he does secretly believe that political leaders should decide things in service of the mandate given them by the electorate, his whole method of work refuses him time to decide anything at all for himself: Benn is always finding out, never weighing up the merits and demerits of policy.

Crosland on the other hand — and this perhaps because he does seem to lack that ultimate ruthlessness of ambition — is a considering man. He seems still to be saying the kind of thing he was saying years ago, not because he has run out of invention, but because, at an early stage of his career he understood things. There is a moral and intellectual consistency about the man which I find immensely attractive. He is civilised and thoughtful in a way that is rare. If the main task facing the Labour party — and it is, as Harold Wilson never ceases to remind us, a movement as well as a party — is to reconcile in the formulation of policy the clamant wishes of the body of the movement with the necessity of any government for leadership by its chiefs, then Crosland is a man who has long thought out that reconciliation. His intelligence and understanding mark him out as a leader.

It is always easy, when parties assemble to debate their affairs by the seaside, for their members to identify themselves with the nation. But it is the electorate as a whole who select governments, not the members of a given party. The electorate are never quite certain what they want, but what they want does seem to be made up of an uncertain mixture between what they like and what they think is good for them. Any party — for example, one led by Roy Jenkins — which advocated unabashed elitism, would certainly fail. Likewise, however, any party — such as one led by Anthony Wedgewood-Benn in unabashed cultivation of sectional interests would, I think, also fail.

Between these two poles, and between the two philosophies of power as action by government, and power as reflection of feelings, the Labour Party now stands. The direction in which it moves of the next decade, towards either pole, or steadily along between the two, will determine its prospects of government, and be of great consequence for the country. The man among the contenders for the succession to Harold Wilson who seems best to understand that is Crosland. The choice for Labour would appear to lie between a presiding mind of Government, and a presiding dervish.

Previous page

Previous page