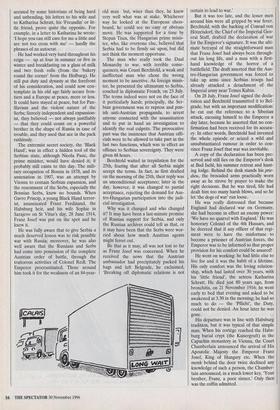

BRITAIN'S UNWILLING ENEMY

Two Germanic emporers fought us in the

first world war Stuart Campbell says the

one who died 80 years ago didn't want to

WHEN the young Victoria was informed by Lord Melbourne of her coming eleva- tion to the throne of Great Britain, she is reputed to have said, 'I will be good.' She then ruled us very firmly for 64 years, try- ing to make the British good too.

Just over a decade after her succession, another 18-year-old inherited an imperial crown, that of Austria, as Franz Josef I. It is not recorded that he made any public avowal of intended virtue, but throughout his long reign he was certainly imbued with that hard-sounding German ideal of Pflichtbewusstsein, best translated as 'sense of duty'. By maternal descent, he was half a Wittelsbach and Victoria was a Saxe- Coburg, and the two houses had in fact been linked by marriage since the previous century.

Franz Josef ruled the Habsburg empire for 68 years, again very firmly, and demon- strated, as Victoria did, that even when Young he had a mind of his own. It was no easy reign — even his own coronation had to be carried out at Ohniltz in Moravia, since Vienna was in the hands of a revolu- tionary mob. It was 1848, when the whole of continental Europe was in turmoil, seething with rebellious ideas of self-deter- /inflation and democracy.

In Hungary, the second state of the empire, Lajos Kossuth, a real rabble-rous- er, was demanding an independent govern- ment, declaring that the Habsburgs were no longer competent to rule and were preparing for war. In a surprise move, however, Kossuth was seen off by a Rus- sian army at Temesvar in August 1849, since Tsar Nicholas saw him as a threat to his own hold over Polish lands. Poland, since 1795, had been partitioned between Austria, Prussia and Russia; the Tsar dis- liked the fact that Kossuth employed Pol- ish-born generals, and believed that monarchs should co-operate to put down revolutionaries.

Franz Josef was not so lucky in Italy: in 1859 he had to reconcile himself to the loss of Lombardy at the hands of the French and Piedmontese, after the bloody battle of Solferino. The essential issue, however, the question of Hungary, was eventually resolved by brilliant statecraft, both on Franz Josef's part and that of Fer- enc Deak, a Hungarian but a realist and one of the wisest politicians of the epoch. To negotiate on behalf of Austria, Franz Josef made an extraordinary move — he hired himself a new foreign minister, Count von Beust, who was not from his own lands, but the ex-prime minister of Saxony who happened to be out of a job. Within a few weeks of his appointment, Beust was in Budapest and at work with Deak. The great compromise, the Ausgle- ich, was hammered out, whereby Franz Josef assumed St Stephen's crown as King of Hungary in 1867, while remaining Emperor of Austria. The Dual Monarchy, which in theory gave the two core nations equal status, was to last 50 years, although the Magyars were to prove as quiescent under what they perceived as a foreign yoke as the Irish.

The remaining problem was Prussia, but after the battle of Kaniggratz, where the Prussians, highly organised and with mod- ern weapons, trounced the Austrian armies on 3 July 1866, Frank Josef was no longer in a position to challenge Bismarck and the latter's determination to unify Ger- many under the Hohenzollerns. When Bis- marck was dropped in 1890, the new Emperor, Wilhelm II, indeed pursued a policy of friendship with Vienna. But Kaiser Bill, that bottom-slapping and dan- gerous humorist, the product of a liberal German father and an overbearing English mother and subject to mercurial swings of mood, was anything but an easy friend.

Franz Josef was by now a lonely man and less self-confident. He had been badly hammered by family loss: one of his broth- ers, Maximilian, died (bravely) in front of a firing squad in Mexico; his only son, Rudolph, committed suicide (after his rather nasty murder of Baroness Vetsera, a 17-year-old mistress), and finally his beau- tiful, beloved and wayward Empress, Sisi, was assassinated by a mad Italian anarchist on the quayside at Geneva. It was this last blow that evoked the cry, 'Am I to be spared nothing in this life?' Often unjustly accused by some historians of being hard and unbending, his letters to his wife and to Katharina Schratt, his `Freundin' or lit- tle friend, prove quite the opposite. For example, in a letter to Katharina he wrote: 'I hope you can still care for me a little and are not too cross with me' — hardly the phrases of an autocrat.

He had worked very hard throughout his reign — up at four in summer or five in winter and breakfasting on a glass of milk and two fresh rolls (from the 'bakery round the corner' from the Hofburg). He still put duty and dynasty at the forefront of his consideration, and could now con- template in his old age fairly secure fron- tiers and a Europe at peace, more or less. It could have stayed at peace, but for Pan- Slavism and the violent nature of the Serbs; fiercely independent and expansion- ist, they believed — not always justifiably — that they could count on a powerful brother in the shape of Russia in case of trouble, and they used that ace in the pack ruthlessly.

The extremist secret society, the 'Black Hand', was in effect a hidden tool of the Serbian state, although Nicola Pasic, the prime minister, would have denied it; it probably still exists to this day. The mili- tary occupation of Bosnia in 1878, and its annexation in 1907, was an attempt by Vienna to contain Serbian expansion, and the resentment of the Serbs, especially the Bosnian Serbs, knew no bounds. When Gavro Princip, a young Black Hand terror- ist, assassinated Franz Ferdinand, the Habsburg heir, and his wife Sophie in Sarajevo on St Vitus's day, 28 June 1914, Franz Josef was put on the spot and he knew it.

He was fully aware that to give Serbia a much deserved lesson was to risk possible war with Russia; moreover, he was also well aware that the Russians and Serbs had come into possession of the complete Austrian order of battle, through the traitorous activities of Colonel Red!. The Emperor procrastinated. Those around him took it for the weakness of an 84-year- old man but, wiser than they, he knew very well what was at stake. Whichever way he looked at the European chess- board, he could see no easy or obvious move. He was supported for a time by Stepan Tisza, the Hungarian prime minis- ter, who, like everyone else, believed that Serbia had to be firmly sat upon, but did not think the moment opportune.

The man who really took the Dual Monarchy to war, with terrible conse- quences, was Count Berchtold, a weak and ineffectual man who chose the wrong moment to be assertive. As foreign minis- ter, he presented the ultimatum to Serbia, couched in diplomatic French, on 23 July. The terms indeed were not on the face of it particularly harsh; principally, the Ser- bian government was to repress and pun- ish anti-Austrian propaganda, to arrest anyone connected with the assassination and to put in hand an investigation to identify the real culprits. The provocative part was the insistence that Austrian offi- cials were to be allowed to take part in the last two functions, which was in effect an offence to Serbian sovereignty. They were given 48 hours.

Berchtold waited in trepidation for the 25th, fearing that after all Serbia might accept the terms. In fact, as first drafted on the morning of the 25th, their reply was an unconditional acceptance; later in the day, however, it was changed to partial acceptance, rejecting the demand for Aus- tro-Hungarian participation into the judi- cial investigation.

Why was it changed and who changed it? It may have been a last-minute promise of Russian support for Serbia, and only the Russian archives could tell us that, or it may have been that the Serbs were wor- ried about how much Austrian agents might ferret out.

Be that as it may, all was not lost so far as Franz Josef was concerned. When he received the news that the Austrian ambassador had precipitately packed his bags and left Belgrade, he exclaimed, 'Breaking off diplomatic relations is not certain to lead to war.'

But it was too late, and the lesser men around him were all gripped by war fever. Berchtold, with the backing of Conrad von Hotzendorf, the Chief of the Imperial Gen- eral Staff, drafted the declaration of war for the Emperor's signature. It was the ulti- mate betrayal of the straightforward man that Franz Josef had always been through- out his long life, and a man with a first- hand knowledge of the horror of a battlefield. The draft asserted that the Aus- tro-Hungarian government was forced to take up arms since Serbian troops had already attacked a detachment of the Imperial army near Temes Kubin.

On 28 July, Franz Josef signed the decla- ration and Berchtold transmitted it to Bel- grade, but with an important modification: he cut out the reference to a Siberian attack, excusing himself to the Emperor a day later, because he asserted that no con- firmation had been received for its accura- cy. In other words, Berchtold had invented the whole episode or seized a wild and unsubstantiated rumour in order to con- vince Franz Josef that war was inevitable.

A copy of the declaration has been pre- served and still lies on the Emperor's desk at Bad Ischl, his summer retreat and hunt- ing lodge. Behind the desk stands his prie- dieu, the brocaded arms practically worn away as he strove by prayer to make the right decisions. But he was tired, life had dealt him too many harsh blows, and so he let 'the dogs of war' run loose.

He was really distressed that because England had declared war on Germany, she had become in effect an enemy power: 'We have no quarrel with England.' He was honorary Colonel of the 4th Hussars, and he decreed that if any officer of that regi- ment were to have the misfortune to become a prisoner of Austrian forces, the Emperor was to be informed so that proper provision for his comfort could be assured!

He went on working: he had little else to live for and it was the habit of a lifetime. His only comfort was the loving relation- ship, which had lasted over 30 years, with his 'little friend', the actress Katharina Schratt. He died just 80 years ago, from bronchitis, on 21 November 1916; he went early to bed that evening and asked to be awakened at 3.30 in the morning; he had so much to do — the `Pflicht', the Duty, could not be denied. An hour later he was gone.

His departure was in line with Habsburg tradition, but it was typical of that simple man. When his cortege reached the Habs- burg burial crypt (the ICaisergruft) in the Capuchin monastery in Vienna, the Court Chamberlain announced the arrival of His Apostolic Majesty the Emperor Franz Josef, King of Hungary etc. When the monk behind the door twice declined any knowledge of such a person, the Chamber- lain announced, in a much lower key, 'Your brother, Franz, a poor sinner.' Only then was the coffin admitted.

Previous page

Previous page