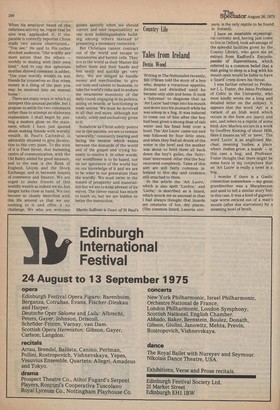

Religion

Worldly wealth

Martin Sullivan

Christ employed the parable as His most constant teaching form and told, in all, forty of them. A parable is like a joke, meaning literally, "the laying of one thing alongside another." One either sees the point or does not, and explanation and moralising are unnecessary. Not all of these stories reaches the same high level and one or two are somewhat obscure. The most controversial and perhaps the most difficult to interpret is the strange tale of the unjust steward or the clever rascal, as it is sometimes called. It seems, at first, to be a rather odd medium for a religious lesson.

A wealthy employer had an agent who was accused to him of certain malpractices. The man was sent for and dismissed. There was no golden handshake and no redundancy pay to soften the blow, so he began to look round at once for some kind of insurance. He found it in the debts of his employer's customers with whom, at once, quite unlawfully, he arranged a very substantial reduction in their liability._ By putting these men 'under such an obligation he knew he had them where he wanted them to be and in due course he would be able to exact his own commission. When his employer heard of this nefarious activity he, rogue that he also was, applauded it. If the parable is correctly reported Christ made two astute observation,. "You see," He said to His rather shocked audience, "the wordly are more astute than the others — worldly in dealing with their own kind." And to cap this aphorism another shrewd comment is added. "Use your worldly wealth to win friends for yourselves so that when money is a thing of the past you may be received into an eternal home."

There are many ways in which to interpret this unusual parable, but I propose to settle for two comments rather than to attempt an elaborate explanation. I shall begin by putting a modern gloss on the statement which I have just quoted about making friends with worldly wealth. St Paul's Cathedral is admirably situated to give illustration to this very point. To the west of it is Fleet Street, that humming centre of communication, with the Old Bailey added for good measure, and to the east is the Bank of England, Lloyds and the Stock Exchange, and in between houses of commerce and finance. We are urged to make friends of this worldly wealth as indeed we do, but danger lurks close at hand. We can become so closely identified with this life around us that we say nothing to it and offer it no challenge. We who are welcome guests sanctify when we should correct and lend respectability as one more indistinguishable building among others instead of presenting a necessary corrective.

But Christians cannot contract out of the world and escape to monasteries and hermit cells. They live in the world as their Master did before them and their hands and feet easily and quickly get very dirty. We are obliged to handle money and merchandise, to give our time and talents to business, to take the world's risks and to endure the wearisome monotony of the daily round, engaging in its politics, sitting on boards, or functioning in trade unions. We must be involved in all that and more, although not totally, solely and exclusively given to it.

Somehow as Christ subtly points out in this parable, we are to remain 'unworldly,' constantly bearing and facing the tension which exists between the demands of the world and of the gospel and trying honestly to resolve it. In other words, our worldliness is to be based, not on our ignorance of the world but on our knowledge of it and we are to be wiser in our generation than the worldly. We must swim in the waters of prosperity and materialism but we are to keep abreast of its waves. The clever rascal has much to teach us, but we are bidden to better the instruction.

Martin Sullivan is Dean of St Paul's

Previous page

Previous page