Burmese memoir

The biggest reclining Buddha in the world

Duncan Fallow ell

We were bumping somewhere around the edge of Rangoon when my crown fell off. "What the blazes! ... thit!" I found myself lisping, it was a sudden and intolerable attack on the amour propre, with a marble jangling in the mouth. If the matchbox airport were anything to go by, this town would not be on the map of the latest in cosmetic dentistry — which may be applied as a rule of thumb to all countries demanding a currency declaration form on arrival. Fourteen kyats to the E when the world knows you can pick up 45 for a quid in Singapore. The Burmese government should up its offer if it wants to encourage tourism, like it says, instead of mooning on oil when it is mostly gas. (I overheard an expert one night passing on confidential discouragement.) After the bargain that was Bengal, one would obviously be having one's nose opened again.

I popped the crown into my pill-box and attempted to come to some mutual arrange ment, not necessarily hostile, with the new frontal gap. "It'th pretty . . I was going to say 'hot.' But already felt clownish. And any jackass could deduce that it was not cold. The tyres were sucking up the tarmac like turf. The scenery was seething, rising, in waves of drunken boiling air. Royal Thai Airways had done their piece, starting with free champagne. We and the weather took it from there. The temperature had already said goodbye to 100 and was making a sadistic bee-line for 110. Would we hit the fridge before it struck?

The open pick-up humped and bone-shook into an elegant suburb, low colonial mansions hugging the fertile mind as if something from heaven had sat on them, glimpsed in gardens of violent hazy growth that coiled and tumbled inward as the buildings stretched out a few hesitant fingers to meet it, sweltering behind flame-trees, tumescent with longueurs, antique yet — WHAM! What? And right in the middle of my circumscription too. Sw0000sh!!

Jeesus, what's — slam, splat! . er, driver?

But he was giggling and safe in his rusty front coop. Crash! and if that is not enough — Splat! again. We had inadvertently landed in the middle of Burma's three — plash! — day water-throwing festival called Thingyan and great buckets of the stuff were being projected at us with as much thrust as possible. Splish splish. Ha, missed, you dog.

"Thank heavens the cases are waterproof — are they?" "Mine are." "Oh lorS" They contained priceless relics, the reward of much toil at the Hogg Market in Calcutta dodging rip-offs. This water-throwing lark sloshes in the Burmese New Year (April 17) and according to a pamphlet "is the Customary way of wishing Good Luck." It is also the customary way of soaking people to the skin and since the Burmese these days see white people, especially intelligent white people, once in a blue moon we seemed to be grabbing all the attention. Our driver was slowing down at the main junctions (or as main as you can get around here) a good degree more than safety required in order that we should miss nothing nor anything miss us, the bitch.

Residents brought garden hoses down to the front gates to greet us and with the childish good humour native to their race proceeded to go berserk. A water cannon struck me between the shoulder blades and I expected to be knocked all the way back to the airport and asked to leave in an embarrassing incident. On the other hand, love and peace signs, screams of delight and "yall0000, baby" were being distributed with like incontinence. Lorryloads of young men in multi-coloured para-military drag, graciously not up to cultural revolution scratch (there were anti-Chinese demonstrations in Rangoon during Mao's second Big Push), came careering round corners with ear-splitting wolf-whistles, blood-curdling smiles, and roars of (presumably — my Burmese is creaky) customary good luck and other carnival brie-A -brae noise. While the driver was pretending to stall at an imaginary set of traffic lights, a beautiful young girl crept up, whispered, I turned, our eyes met, and my cheek was sent scarlet by a stinging douche. What fun!

There is only one place to stay, the Strand Hotel, built for the Sarkie Brothers who also ran the Raffles in Singapore, and still crocked up with Dunn & Bennett of Bursiem vitreous ironstone. There was an atmosphere from the word go, a sullen, quasi-affronted indifference to one's presence, unless you were slipping them dollars by the yard for special favours such as a postage stamp for a letter, that is grotesque in its churlishness, for it lacks all dignity or self-respect. It is a rare characteristic in India. The Indians' ingrained habit of constantly touching foreigners for pennies can be maddening but it is understandable and ingenious and does not obfuscate their hearts. It hardly exists at all in Thailand where the dollar barrier, should it appear, is broken with a smile. It is more common in Ceylon. It is particularly common in lesser socialist and communist republics, mainly among non-rural classes. This is not a political statement, just an observation. It is an extremely pitiful syndrome since it lacks that generosity of spirit which informs all civilised peoples with a sense of their own value as opposed to price. The desire for material benefit is universal but it should not mean one bears acrimony to all except those bringing goldmines. But the keynote of this particular attitude is that you do. And unfortunately it seems to be on the increase in Britain: the imminent monopoly of cash-nexus in society which by a none too subtle paradox poisons the commonweal and kills prosperity. There is no buoyancy in it, only envy, stasis and death.

The sour puss with the don't-bother-me-now act was maladjusted to the brou-ha-ha outside and blinked at the drowned rat with the front tooth missing. This edifice to the derriere vague was not exactly ripping at the gills so we were sure of rooms. Mentally he was trying to come to terms with the situation. Where did we fit? Not old enough to be American humanoids on an international formica-top joyride, not dumb enough to be hippies avatar-bound, definitely Esso was not our number, the fine monsoon worthy cut of the jeans pronounced us credit-able, not to mention the carillon of duty free liquor one or two bottles over the odds, maybe three. He fiddled among the room keys, patently trying to find for me one with a delayed insult attached to it. I stood my ground. Steam began to rise off my shoulders, small puddles round the feet on the teak parquet (of course I had removed my customs-officer-proof shoes when the first barrel slopped into the buggy). All the same, something in his eyes, something liverish held tremulous by wires, told that he would love to raise an objection, to bilge somehow. Well, his mute phobias were of no concern to me. I was simply longing to change. Now puddles were spreading around the suitcases: several were about to join in congress and produce a baby lake. In the wings porters undulated waiting for the word. If he doesn't get a move on with his nonsense this leaking old hulk of a neo-classical barn is going to sink! Besides the visa only grants one seven days and it was plausible that half of them were to be exhausted by fluttering formalities.

We signed. He handed me a letter. Little gasp. Rather a jink after all this phoney palaver. It was from a friend of mine, it was cellotaped across the back, it had been opened and checked out by a government gastropod in khaki underpants with a pistol on his arse. I hope he marked the contents, priceless low-down on the big wide world to make a sentry pop his fly buttons one by one. It was a list of all the most exotic bars between Bombay and Tokyo with details in dramatic guide-book code of the specia/ites de rnaison. "No stars against anything in India or Burma," he had written. We had cased those places already, mind-cranking but chaste.

I signalled a dwarf in white ducks who came forward grinning gold. What's he hoping for?

thought. This indigenous peasant charm, you can't crack it very easily. It is a simple thing to place the wrong interpretation on a tight handshake which suddenly, develops into a kind of palm massage. When is a greeting a come-on? Better to bark up the wrong tree than no tree at all, I concluded. "And your friend, please." NattiraIly the iron lift was out of action — oh glorious decrepitude! We followed them up two flights of a big brown staircase, pumping away with their short thick calves under the sickening weight of the luggage.

With only a holster of very important documents to oppress me, 1 was all over by the first flight. "Small but tough, aren't they?" said Miss Moffett. "Every cat to its kennel," I replied, heavily depressing a balustrade. After an impressive acceleration, the lunch-time temperature was now cruising at a steady 106: There was a filthy trail up the stairs: thingyan run-off, dust, sweat. Of the second flight and what followed there is little to say, a whirligig of dreams: cold beers, cool showers, fresh 'white linen, impression of old wood, rattan, wicker, a wide green bed heaving around the room— chink of coins and collapse No longer run by its Armenian, the Strand is now in the care of a morose Burmese manager whose notion of concerned hospitality confines him to his office, Gordon's Export Gin and sleep for most of the day. Complaints must be made however; even though nothing is done about them, complaints must be made to prevent guests turning ga-ga with frustration and drooling froth in censorable postures in front of new arrivals. There are complaint books lying about. These were much in demand during our stay because the water-throwing bit had left the rooms without running water. A thing like that can turn your skull inside out then shave it clean when the temperature trips gaily over a hundred every day. When I put this to him the manager suggested I "go somewhere else then." I scribbled my complaint in a polyglot tome of driven neurotics with a choked frenzy that had anguish and anger punching each other for possession of the soul, then set off to hustle a shave from some source possibly still irrigated.

But, as one will, I had almost adapted to this monstrous deprivation, having indeed disco vered a tap that dripped at the end of some alien service corridor, when on the afternoon of the sixth day the ogre rang upstairs. He would knock 10 per cent off the room charge, piddling grace in the tropical circumstances, since the overall bill had a 10 per cent service charge, with another 10 per cent something-else charge on top of that: possibly a breathing tax on the lungs for making such use of the local aether as was affordable. Nonetheless, his gesture would have been sufficient. Had honour come to him at last? Sadly, no. The beast had discovered that on that same evening we were going to a party given by the Ambassador to celebrate Queen Elizabeth's birthday and would be chatting volubly to several of his employers. Recom mendation to the Department of Tourism: in the interests of world peace, this man must go! Although the Burmese people are by instinct warm-hearted, the petty officials are needlessly foul, in the deliberate, painfully obtuse way I last remember from crossing the Berlin Wall. Those East German border guards with their bullet heads and sub-human sympathies who insist on your filling out form after form but they are all printed in German so you are perplexed by what to put where. They refuse to explain, even though their English is sufficient to enable them to do so. Therefore you wait until a bilingual fellow traveller arrives to tell you that here is where your names goes, there your address, there the money in your possession, and so forth. A very illiberal exhibition they put on for your arrival in the capital of East Germany, and when you finally pass over, with the sensation of machine guns trained on the backs of your knees in case you break into a• strut, you wonder if the war finished yesterday or is still going on, with these stormtroopers goosing around, bomb sites, a population meanly clad and in earshot of the glitter across the barbed wire, the shops bleak, many great buildings of the Unter den Linden pitted and crumbling, the cathedral shuttered with corrugated iron and rooks nesting in its tufted towers, high spirits verboten. Fanatical Nazism to Fanatical Marxism without hardly moving a brain muscle. Small wonder they are the most devoted communists in the bloc. Although I hear that the mentality of parts of Texas can, Burma cannot compete with that. Climate and prevailing national character will not permit it.

Nonetheless the Strand reception staff, the most meagre of the breed, gathered like blocks of dry ice behind the counter, drop the lobby temperature by several notches. As there is no air-conditioning in the public regions of the hotel and there were frequent battles to be fought in this arena against over-charging, the chilling effect of the personnel concerned was quickly construed as an advantage. And the light whirr of fans is definitely more chic. The debility of this institution, nodding in its time capsule, gives it a uniqueness that would vanish if disturbed. To call it a period piece would be banal. Its singularity runs deeper than that, characteristic of the town whose premier hostelry it is. And the floor staff are enchanting, though mischievous at times. All the same, whereas fans in India generated a near-tolerable atmosphere, Rangoon must be a markedly hotter place, and against the will one was frequently obliged to retreat to the cold comfort of the bedroom to outwit a spasm, then jangle for room service. If the manager wanted to do something intelligent, setting aside his brain capacity for the moment, he should, instead of permitting his immediate underlings to huddle together for cool in one corner of the building, spread them about at strategic intervals where their presence would be a public benefit more in keeping with the aims of the Socialist Republic of the Union of Burma, at least during the pre-monsoon heatwaves, at least at tea-time.

New Year, In the year of Burma, 1337: this is unsurprising. The editorial of, The Working People's Daily is not obvious. "The air is still echoing with the Thingyan thangyats made memorable by their artistic blend of fun and social criticism." "People's Forum: frank views and comments" today gives advice from the scriptures: "Six Evils of Drinking: Dwindling of wealth, becoming argumentative, becoming sickly, earning bad reputation, tending to get unrobed, and ignorance." "Five Duties of Children" begins well enough: "Feeding one's parents unfailingly." Then burns itself out in cliche. The only other frank view is a letter from Warren Edwardes of Colindale, London, describing the acquisitive advantages of his "Fifty Stamp Club." As the same paper reported the following day, it was a "Quiet New Year Day in Rgn." "Buddhist devotees cleansed the Buddha images and stupor of the Shwedagon Pagoda and chanted mantrams to bring peace and prosperity in the New Year. Elders spent the day quietly at the monasteries observing sabbath and offering alms to the monks . . • Organised groups freed fish at the Inya Lake... while others freed animals. . . Young men and women visited the homes of aged persons arid shampooed the old ladies. . ."

The editorial on that day was called 'Pride 8c Prejudice': "Burmans are a proud people. They have always been a proud people and they always will be a proud people. They are proud of being Burmans and they are proud of being referred to as a proud people," etc. Doesn't anyone up there at the Ministry of Information which publishes this juvenile self-abasing trot have even a vestigial sense of humour? Not all however were pleased to welcome -another year. April 19— "The body of a mother with two dead daughters tied to her wrists was recovered this morning from the Railway Independence Ground lake at Insein." What a place to go .

At the pictures Slaughter was in its fourth and final week at the Thamadon, Diamonds Are Forever in its eighteenth and final week at the Gon. Both were to be replaced by. the Shaw Brothers' New One Armed Swordsman. The whole town was on heat for it and there was a violent riot for tickets when it arrived which gave birth to many vendettas. The Guardian, Rangoon's other English-language daily, the one the Strand prefers to slip under your door, and also published by the Ministry of Informa tion, is agreeably if only slightly more languid and does not appear on festival days. On Sunday, April 20 the editorial puffed on a cheroot and said 'Mercury rose to what might be an uncomfortable 108° , and those not quite used to these climes might have wished they were at a higher altitude in another region.' A gin and tonic expands to gargantuan potency but there is rarely need to urinate. Excess liquid passes directly out through the skin.

The advantage of Rangoon is its size. You can get to know it in a day and exhaust its possibilities in a week, given that the people are kept by various devices at arm's length. Your embassy staff will be delighted to see you because Rangoon is a bit of an outpost and most of them shoot off to Bangkok for a few days to idle in the shops, cinemas and clubs when they can, armed with long shopping lists from all the neighbours. That the visa only grants you a week anyway is shrill blessing. At this time of year it is out of the question to travel further afield to the old Royal capital of Mandalay, to Pagan whose 'Four Million Pagodas' (a trial even by jeep!) were sacked by Kublai Khan in the thirteenth century, to Inle Lake 'noted for its floating islands and leg rowers,' and sure enough there is a picture of them rowing away with their legs. It looks slightly foolish actually, means all out of proportion to ends, like a man who uses a pole vault to traverse a ditch, but I daresay they have their reasons. All this is out of the question unless you wish to offer yourself as sacrifice to Phoebus or are of the temperament to fly everywhere for an afternoon to scratch the pictures in a guide-book.

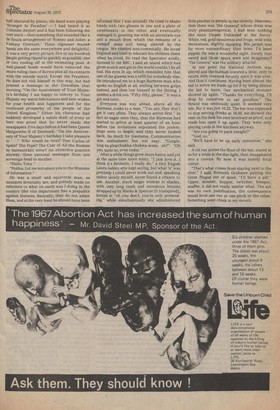

Even Pegu, fifty miles north of Rangoon, seems impossibly faraway, an exceeding distance to go merely to look at Buddha reclining, 181 feet long, 46 feet high at the shoulder, or a shrine containing two of his hairs, when both structures are superseded in Rangoon, although you would pass the Impe rial War Cemetery en route where 27,000 lie dead, the tip of the iceberg. Oh yes, we had

come at the right season, confinement to the town gave one willy-nilly a chance to develop some feel for the place. At any other season one would be sorely bitten for lack of time. "But, Agamemnon, we must fly up to those ruins which that nice little man in black said were the best ruins in the whole world." "A'm sorry, my dear, but a'm done with takin ma shoes off. Besides we leave for Hong Kong tomorrow. Maybe they have some ruins there."

If in this short time you manage to strike Up a genuine acquaintanceship with a local, thus contaminating him/her for the Buddha/Government, it will scarcely be less than a miracle. As an added safeguard the authorities regularly close down anything which might conceivably turn into a night club or public bar, to keep the language of their bodies as mysterious as the language of their alphabet. My letter mentioned only one, the Mayfair Club in Kokaine Road. It sounded perfect, too perfect. It has been closed down and the lady who ran it imprisoned for seven years. Presumably she offended the scriptures. "Six Causes of Destruction of Property: drinking, wayfaring at unearthly hours, regaling on entertainments, gambling, bad and loose company, and idling." And one year for luck makes seven. It seems that the Inquisition lives, having changed black for saffron yellow robes, punitive Marxism set on the ethics of Buddhism.

The only other draw was the Nanthida Beer Pub along the riverside walk, owned by the Strand Hotel, and no more than a café with a snatch of a view across the Rangoon river, delta tributary to the Irrawaddy. But by attracting more than a dozen patrons after sunset this was obviously getting out of control and turning into a slop bucket of unnameable vice, so was similarly extinguished. It is not that Rangoon has a curfew on it, just that last orders are at 8 pm, which amounts to the same thing. If ever a capital were made for the pocket — there is absolutely nothing which might induce you to .squander, not even local handicrafts (with a few inexpensive exceptions) — it is this one, built on a small grid pattern by the British with some very eye-catching public buildings fraying stylishly at the edges, like Odeons in the oriental manner abject at the passing of the silver screen. Red tape towers and turns yellow in the lugubrious interiors. Where once a thousand clerks laboured with pens, setting up a sound like the roar of locust wings, now one or two squeak in large ledgers, on enormous teak desks, as mice will nibble at rind. There is a rareness in this, not to be found elsewhere.

Some prosaic facts about Burma to balance the foreground. Slightly larger than Afghanistan, rather smaller than Zambia. Population 28 million, ten times that of Laos, Puerto Rico or New Zealand, and equal to that of Persia. With the subjection of Mandalay in 1886 all Burma became part of a much larger territory called British India. Xenophobia, endemic, was becoming active by the 1930s. Occupied by Japan during the war who built the famous railway. An independent republic outside the Commonwealth, January 4, 1948. Owing to the powerful centrifugality of the regions (something like 100 languages and significant dialects are spoken daily within the borders) parliamentary democracy never got off the ground. A military dictatorship since 1962 under General Ne Win. He has since civilised himself by dropping the title 'general' and ordered his administrative staff to do likewise. Rebellion is still a problem in the north, but its basis is tribal rather than ideological and the communists are divided by white and red flags. Burma is contiguous with China, India, Laos and Thailand. It provides a policy of stringent non-alignment. This, coupled with U Ne Win's unbending 'Burmese Road to Socialism' which nationalised virtually everything except monasteries and street vendors, has had a disastrous effect tin the economy, exacerbated by wholesale expulsion of Chinese and Indian traders.

Until 1962 Burma had the world's largest exportable rice surplus. At its peak before the war it was more than three million tons. It has now sunk to one fifth of this: rice accounts for 60 per cent of the economy. Like our own the Burmese government hangs naively on oil as saviour. Tourism is theoretically encouraged but Burma's poverty and continuing suspicion of foreigners means that the country remains unsullied by the commercial trappings which follow holiday makers and coarsen so much else in Asia. Thus for travellers it retains qualities of discovery and fascination. The national sport is soccer, followed by hockey and cricket. Reuter regularly brings to the Guardian such sports headlines as 'Derby County Poised For First Division Title.' In fact the fortunes of British football teams are given major press coverage throughout the East, quite as muchas the London Stock Exchange receives. Anglo-Scottish matches, particularly the cretinism of the Scotch fans which usually attends such occasions, causes them to jump up and down with glee, as if it proved something they had long suspected. In addition to a President, Burma also has an Earl but, a great-grandson of the last Empress of these tracts though he is, he has no territorial rights, an admirable fantasy.

Some other facts. Being Theravada Buddhists the people do not stir in the face of 'economic realities' any more than the House of Commons does, and if they did the good ' President could imprison them for it, They take an unnatural interest in the clothes worn by foreigners. I believe Freud had a word for this.

An alarming number of older people who recall ,the more prosperous pre-war days are passionate Anglophiles and say they want the British

back, then stop short with phrases such as 'the floor has ears.' Since the British (C of E on the whole) are up a similar gum tree themselves this is pleasant but slightly embarrassing.

Rangoon's fabled Shwedagon Pagoda, "the most beautiful and magnificent structure in the world" according to a pamphlet, is certainly the richest shrine of its kind, 2,400 years old, and rockets 326 feet off the platform. The plantain bird is armoured in solid gold plates and crowned with 5,500 diamonds among other winking things. It is at its most transcendental seen from a distance above the green trees across the lake. On site, attended by hundreds of kiosks in pointed allegorical contrast and small temples heavily tinselled and larger shrines dedicated to all the days of the week (from which the Burmese take their names according to the one on which they were born), the complex is a Buddhist Disneyland: an experience wondrously sensual. Thailand's Phra Pathom Pagoda is more than 50 feet taller but is ribbed like an inverted ice-cream cornet and stuck on top of a Prussian helmet.

Rangoon's two most modern buildings, still in course of construction, are a sign of the times, or lack of them since both might have been designed several thousand years ago without a blink. One is the Karaweik, a mythical bird being reproduced in stone, plaster and wood on the Royal Lake as a restaurant and shop of Burmese crafts for tourists.

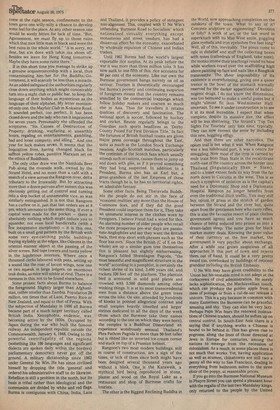

The other is the Biggest Reclining Buddha in the World, now approaching completion on the outskirts of the town. What to say of it? Concrete sculpture or engineering? Devotion or folly? A work of art, or the last word in superkitsch with its Mae West smile, goggling glass eyeballs and iron eyelashes five feet long? Well, all of this, inevitably. The pious come to ogle in disbelief and stuff the collecting boxes with notes (cathedrals of England, take note), the monks intone their teachings round its base while workers crawl over the scaffolding high above painting up face and nails like a Bangkok transvestite. The sheer impossibility of its. existence is overwhelming, giving one a queer tremor in the bowl of the stomach normally reserved for the darker apparitions of hallucinogenic drugs. I do not know the dimensions, was too bemused to make a useful guess but it might 'almost fit into Westminster Hall: uncertain. To see it under construction is to see it at its most incredible. I expect that when complete, despite its massive size, the effect will be less shattering. The Strand's Top Ten Sights For Tourists' only lists nine, typically. They can now correct the error by including this new, boggling effigy.

And then there are other narcotics. The opium trail is not what it was. When Rangoon was a less hidebound port, it was a centre for smuggling. Now most of the crop is carried by mule train from Shan State in the recalcitrant north-east of the country across the border into Thailand (linguistically Shan = Siam), , and to a lesser extent finds its way from the far north down to Calcutta in the west. This is as much a symptom of isolation as is the capital's need for a Diplomatic Shop and a Diplomatic Hospital. Rangoon no longer benefits from even the traditional illicit traffic. You may still buy opium or grass in the stretch of garden between the Strand and the river but, quite apart from the gentlemen here who carry rifles, this is also the favourite resort of plain clothes government agents and you have as much chance of being seduced into prison as into a dream-laden sleep. The same goes for black market money deals. Knowing the poor value of their currency on the free market, the government is very psychic about exchange. After a while one grows suspicious of all approaches in this part of town and rejects them out of hand. It could be a very pretty sward too, overlooked by buildings of reticent grandeur including the British Embassy.

U Ne Win may have given credibility to the Union but his unstable mind is not adept at the corkscrews of civil administration_ He sorely lacks sophistication, the Machiavellian touch, which can produce the golden apple from a mess of pottage or from a cul-de-sac release a unicorn. This is a pity because in common with many Easterners the Burmese can be graceful, amusing and shy. They can also be very lazy. Perhaps Papa Win fears the renewed insinuations of Chinese traders, should he soften up on central control. In South-East Asia there is a saying that if anything works a Chinese is bound to be behind it. This has given rise to pogroms, along the lines of those directed at Jews in Europe for centuries, among the nations to emerge from the recession of Colonialism. As a result, in some places there is not much that works. Yet, having application as well as acumen, chinatowns are still two a penny all the way to San Francisco, dealing in everything from bathroom suites to the siren elixir of the poppy, at reasonable prices.

If you go into the Burmese National Museum in Phayre Street you can spend a pleasant hour with the regalia of the last two Mandalay kings, only returned to the people by the United

Kingdom in 1964 battered gold and silver trays, goblets, bowls, costumes, daggers and swords, fitted with luminous but badly cut gems. You will also see a striking example of bad taste: the sole addition to this accumulation of venerable and cumbersome kitchenware, the crown jewels, is the commonplace insignia of U Ne Win. It is a small black box which at a glance could be a packet of fags mistakenly left behind by a cleaner, a gold Maltese cross on a blue ribbon, and appears so puny, so pompously insignificant surrounded by all the dented glory of the kings, that I wonder a monk has not pointed out the implied humiliation as opposed to humility in so silly a juxtaposition. Question for the Curator: could it not be given a tiny plinth of its own, preferably round the corner? Because they are rather grand salvers, you know.

He does not have it all his own way: The closure of the universities proved that. Conventional student boisterousness, born from the sudden and simultaneous discovery of both freedom and more ideas than one can rightly handle, had not been the cause but a highly unusual, laudable exercise by the students in teaching the President good manners.. The point of contention was the burial of U Thant. As the most distinguished Burman in many generations the students wanted him to be given an honorary state funeral and a memorial. Presidential jealousy being what it is, only permission for a standard family burial was granted. The students thought this was the anti-individualism of Marxism taken too far, in short, humbug. They respected U Thant as a man whose goodness and wisdom had earned him the affection of the world. In his own country something more than X-marks-thespot was loudly called for. There were protests. These were subjugated. There were riots. What was a poor President to do but shut down the institutions altogether? When we arrived they had been closed for four months, although some of the innocuous, pedestrian scientific faculties were preparing to open again. The incident has lost U Ne Win much standing in the country, as casual conversations unanimously affirmed. A tourist guide said to us that the President was 'too old to know what's going on any more.' He seems to occupy something of the same position as Tito, without provoking a comparable pang in the hearts of his countrymen. The incident illuminates a) the personality of the President, and b) how much at odds it often is with the personality of Burma. It is significant that it was not a theoretical controversy. The Buddha, being a hyper-realis tic if contemplative fellow, doesn't give two hoots for dogma.

The Ambassador's Party and some circumstances thereto. The birthday of Queen Elizabeth was perfectly timed. Out last night in Rangoon and a beautifully timed finale to an erratic seven days, a single week, beginning with Burma's most exuberant annual festival and ending with the Embassy's most prestigious annual function, the two celebrations embracing drowsy and curious events: the week had acquired perfect form. The American Ambassador's private house would be Palm Springs' finest hacienda. The British Ambassador's would look opulent and uppity even in Kensington Palace Gardens. What remains of the grand old life in both quality and style is more and more confined to the international diplomatic circus. In Rangoon it is exclusively. their province.

Sunday lunch at the British Club had not been the grand old life exactly, rather homely and uneventful in fact, as befits Sunday lunch. There were only half a dozen or so of us there and but for the white-coated barman putting his elbow into a whisky sour, the dart board, and the jumble sale pinned to green baize, it could have been somebody's house. The usual talk of amoeboid dysentery, how a jog to Asia makes you realise the extraordinary variety and magnificence of European culture, have you been to Pagan? — no, it's too hot — you must go to Pagan — I know but sorry, the weather, it's too much for a poor white boy and I'm not wearing one of those hats — oh, you mustn't believe all you hear about mad dogs, you know — I don't, I don't, I'm speaking from experience, I went bananas in a trishaw in Madras — my dear, you must watch the salt — oh, I do, I do, I watch it all the time now — more beer? Thank you, yes, lots more beer. You see, there were only fans again.

One has to admire their grit: several faces had a purplish, lathered look, dark stains 'spreading from the armpits, quietly suffering. Arnoeboid dysentery reappeared. A very tall, very blond, very skinny young Englishman in horn-rimmed spectacles knew all about it. "It's vile. You have to move the bed into the bathroom and even that's not enough, sometimes." Dysentery and archaeology were his special subjects. His wife, very French, very loquacious, very thirsty, mentioned Salisbury Cathedral — she had not seen it. Oh, you must see Salisbury Cathedral. I know, I know! We were off, all the way from the nave of Durham to the ceiling of Vierzehnheiliegen, and back again by a different route. Only the knell of tea-time averted a set-to on functionalism versus aestheticism in the design of terminal railway stations (Rangoon has a very beautiful example which marries both, incidentally). It was plain neither of us had had a decent jaw on the best architecture in the world for months. I felt wonderfully euphoric. Beyond that window Indian labourers were wandering up and down the garden path with bricks on their heads, doing something to an outhouse.

One of the most attractive features of the city lies in its automotion. Because of very high tariffs on impcirts (most of which come from Japan) and the absurdity of Burma ever being capable of manufacturing vehicles for itself, all the cars are immensely old and a number of them, especially those for hire, are immensely large. Only the cars of the diplomatic corps, and a few government officials whom seemliness denies a' jeep, are new: perky, polished, and compact in keeping with the way we live now. The rest belong to another age entirely, patched up with string, door handles missing, smell of torn leather and veneer cracked or totally dismantled by humidity, rattle of rusty components, no one knows what or cares, or are overdaubed with the agitative colours usually found in the modern western kitchen of our chain-store housewife (now, chain stores are things they do not have time for out East). They have gears, which drop out, when you cough, boots that swing up and down with the road, it is quite common as you are out walking to see an axle give up the ghost and snap before your very eyes, but if the suspension still holds the ride is one of sumptuous, dog-eared comfort, inherited from the days of carriages 'and brought to a high point by the 'thirties' technology of wealth, albeit interrupted from time to time by honks, lurches, and small inexplicable combustions.

Such was the transport we had arranged for the party. It arrived at the door as a drunkard rolls up to a conversation — unsteadily, with noisy gestures of social amplitude, and absolutely convinced of its own rightness. No two. ways about it, this was the car for the occasion. Fender and grille glinted under a jaundiced moon, vast humpy black body stretching way behind to lose itself in the umbra of the next block, wheels walled in very off-white splotched with mud, futuristic H. G. Wells mouldings all somehow swept back in an ungainly but well-meaning attempt at the streamline, and one could barely discern in the lamplight the upholstered internal haunches where we were to repose for a few minutes on maroon hide rubbed to a delicious softness. And, golly, I was dressed for it too, by Molyneux. This pinched black bum-freezer jacket with high padded shoulders and bobbled velvet side flaps to impossible pockets (all swept back in a very successful streamline) had obviously been accompanied by a similarly elegant black pencil skirt at some stage in its career. It fitted so snugly that to wear a silk shirt underneath was very nearly too much. For me to wear it confirmed me in my own era and yet the garment was very likely built in the same year as the limousine, although the condition wasn't to be compared, a little bit of the here-and-now-in-the-west which I had introduced into some of the nicest parties in Asia. 1337 indeed! Whatever next.

I handed Miss Moffett in diving acolletage into the car, after the door had been kicked open from inside. The handle wasn't off, merely inoperative. All that was lacking were the bodyguards of Chicago gangsters lining up on the hotel steps either side, machine-guns erect. The other guests could zip up in their tinny Toyotas and Cortinas and Fiats and Mini Mercs, but we should drive at an irregular snail's pace, a mixed metaphor on wheels, and

barely squeeze through the porte ere as the Good Lord intended.

His Excellency, formerly HM's Ambassador to Nepal, is Mr O'Brien, a neat and charming man, as ambassadors invariably are. He was standing on a piece of crazy paving when we were announced (the party was out of doors, naturally). He had been standing on it for some time and was to stand on it a good deal longer. In fact he could not have had much of a party at all because while the last guests were arriving the first guests began to leave and he had to go through it all again, substituting 'goodbye' for 'hullo.' Perhaps it is all in the interests of diplomatic immunity. His wife, in common with many such wives in my experience, was bubbling over. Maybe this is also FO policy to counterbalance the husband's necessary probity.

Buttoned up very smartly on the tennis court

half obscured by plants, the band were playing 'Stranger In Paradise' — I had heard it at Colombo Airport and it has been following me ever since — then something that sounded like a de Souza arrangement of 'Romeo and Juliet: a Fantasy Overture.' These zigeuner muzak bands are the same everywhere and delightful. It was a very pretty picture, five or six hundred People getting ripped as quickly as possible, one or two cooling off in the swimming pool. A Well-placed bomb would have removed the entire ruling class of Burma plus all its contacts with the outside world. Except the President. He does not risk himself in this way, but had printed a message in the Guardian that morning. "On the Anniversary of Your Majesty's birthday I am happy to convey to Your Majesty my warm felicitations and best wishes for your health and happiness and for the continued prosperity of the people of the United Kingdom." Either his character had suddenly developed a subtle shaft of irony or here was proof that he never reads the newspapers. Five days before it had been Queen Margarethe II of Denmark. "On the Anniversary of Your Majesty's birthday I take pleasure in . ." Who would -be next? Don Carlos of Spain? The Pope? The Czar of All .the Russias by bureaucratic error? An attractive practice anyway, these personal messages from one sovereign head to another.

"Hullo, Tony."

"Hulloa. Let me introduce you to the Minister of Information."

He was a small and equivocal man, as ministers invariably are, and politely made no reference to what on earth was I doing in the country (the visa department has a prejudice against literates. Basically, they do not admit them, and at the very least he should have been informed that I was around). He tried to shake hands with two glasses in one and a plate of sweetmeats in the other and eventually managed it, greeting me with an uncertain eye and a mouth from which the remains of a canape' were still being cleared by the tongue. We chatted non-commitally. He loved England and tried to educate his children there when he could. He read the Spectator avidly, listened to the BBC. I said an island which had given scotch and gin to the world couldn't be all bad. His eyes lit up, which reminded him that one of the glasses was a refill for somebody else. He introduced me to a huge Burmese man who spoke no English at all, smiling between gulps instead, and then lost himself in the throng. I needed a drink too. "Fifty-fifty, please." It was a gin and tonic.

Everyone was way ahead, above all the Burmese, soaks to a man. "You see, they don't get it very often. They always arrive first." In fact so eager were they, that the Burmese had started to arrive at least quarter of an hour before the invitations stipulated the junkettings were to begin, and they never looked back. So much for Gautama. Communication was enthusiastic but not easy. "Gurgleting-ta-plopchukka-chukka-weee, eh?" "Oh Yes, quite so, even today."

After a while things grew more hectic and yet at the same time more misty. "I just love it, I think it's fantastic, I really do," a tiny Engish Laura Ashley-ette kept saying, but what 'it' was precisely I could never work out and, speaking rather slowly myself, never found a chance to ask. Another, much larger woman in shades, with very long teeth and enormous breasts strapped up by Marks 8c Spencer (it transpired), butted in "oh you don't, you're only pretending," while simultaneously she administered little pinches to people in the vicinity. Heavens, then there was 'the General' whose dress was truly phantasmagorical. I had seen nothing like since Utopia Unlimited at the Savoy. White, red, gold epaulettes and frogs, wild with decorations, slightly stooping. His jacket was far more extraordinary than mine. I'd been pipped. He was a wonderful sight. Surely that sword and those spurs were not imaginary? The General' was the military attache.

At one point the National Anthem was played and the hubbub lowered a little, only to return with renewed ferocity once it was over. And thus it continued. Having been almost the last to arrive we made up for it by being almost the last to leave. Our mechanical monster showed up again. "Thanks for everything, I'll drop by tomorrow to say goodbye." The Strand was ominously quiet. It seemed very late. But it was just 10.25. The bar was supposed to stop serving drinks at 10.30, we showed the man on the desk his own brochure as proof, and made him open it up again. They were only playing cards in the kitchens anyway.

"Are you going to pack tonight?"

"God, no."

"We'll have to be up early tomorrow," she said.

A rat ran across the floor of the bar, stared at us for a while in the dim light, then disappeared into a crevice. By now it was merely local colour.

"That's what comes from staying next to the river," I said, Kenneth Grahame putting the Great Plague out of mind. "I'll have a pill." Upper, downer, hopper, twitcher, bleeper, snuffer, it did not really matter what. The act was its own justification, the consequence would level one out at one pitch or the other. Something went chink in my mouth.

Previous page

Previous page