ARTS

Exhibitions

Frank Lloyd Wright: Architect (Museum of Modem Art, New York, till 10 May)

Construction of a blockbuster

Michael Wise

Among the scores of anecdotes about Frank Lloyd Wright's brazen self-esteem is one involving his testimony in a court case describing himself as the world's greatest architect. 'Well, I was under oath, wasn't I?' Wright is said to have quipped later on.

Thirty-five years after his death, Frank Lloyd Wright remains an American folk hero and one of the most influential cultur- al figures of the 20th century. Much of this can be attributed to his extraordinary tal- ents, the rest to Wright's knack for self- promotion that turned him into the first media-star architect.

Over the past two years, no fewer than a dozen books about him and his work have been published in the United States. Many of his buildings are undergoing lavish restoration. His mythic life, said to have been the inspiration for the architect Howard Roark in Ayn Rand's novel The Fountainhead, has been immortalised in Daron Hagen's opera, Shining Brow.

Now, New York's Museum of Modern Art has devoted the largest architectural exhibition in its history to Wright. Touted by some as the architectural answer to last year's blockbuster Matisse exhibition, the massive show spans two floors of the museum.

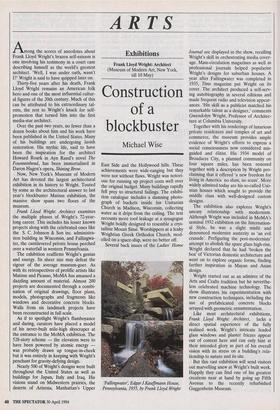

Frank Lloyd Wright: Architect examines the multiple phases of Wright's 72-year- long career. This includes his lesser known projects along with the celebrated ones like the S. C. Johnson & Son inc. administra- tion building in Wisconsin, and Fallingwa- ter, the cantilevered private house perched over a waterfall in western Pennsylvania.

The exhibition reaffirms Wright's genius and energy. Its sheer size may defeat the vigour of the average museum-goer. As with its retrospectives of prolific artists like Matisse and Picasso, MoMA has amassed a dazzling amount of material. Almost 200 projects are documented through a combi- nation of original drawings, floor plans, models, photographs and fragments like windows and decorative concrete blocks. Walls from six landmark projects have been reconstructed in full scale.

As if to spotlight Wright's flamboyance and daring, curators have placed a model of his never-built mile-high skyscraper at the entrance to the MoMA exhibition. The 528-story scheme — the elevators were to have been powered by atomic energy — was probably drawn up tongue-in-cheek but it was entirely in keeping with Wright's penchant for gravity-defying design.

Nearly 500 of Wright's designs were built throughout the United States as well as buildings for Japan, Italy and Iraq. His visions stand on Midwestern prairies, the deserts of Arizona, Manhattan's Upper East Side and the Hollywood hills. These achievements were wide-ranging but they were not without flaws. Wright was notori- ous for running up project costs well over the original budget. Many buildings rapidly fell prey to structural failings. The exhibi- tion catalogue includes a damning photo- graph of buckets inside his Unitarian Church in Madison, Wisconsin, collecting water as it drips from the ceiling. The text recounts more roof leakage at a synagogue Wright boldly designed to resemble a crys- talline Mount Sinai. Worshippers at a leaky Wrightian Greek Orthodox Church, mod- elled on a space-ship, were no better off.

Several back issues of the Ladies' Home

Rallingwater', Edgar J.Kauffmann House, Pennsylvania, 1935, by Frank Lloyd Wright

Journal are displayed in the show, recalling Wright's skill in orchestrating media cover- age. Mass-circulation magazines as well as professional journals helped popularise Wright's designs for suburban houses. A year after Fallingwater was completed in 1935, Time magazine put Wright on its cover. The architect produced a self-serv- ing autobiography in several editions and made frequent radio and television appear- ances. 'His skill as a publicist matched his remarkable talent as a designer,' comments Gwendolyn Wright, Professor of Architec- ture at Columbia University.

Together with his renderings of luxurious private residences and temples of art and commerce, the museum provides ample evidence of Wright's efforts to express a social consciousness now considered mis- guided and elitist. His 1934 model of Broadacre City, a planned community on four square miles, has been restored together with a description by Wright pro- claiming that it offered 'a new freedom for living in America no slum, no scum'. More widely admired today are his so-called Uso- nian houses which sought to provide the middle class with well-designed custom designs.

The exhibition also explores Wright's uneasy relationship with modernism. Although Wright was included in MoMA's seminal 1932 exhibition on the Internation- al Style, he was a slight misfit and denounced modernist austerity as 'an evil crusade'. Prefiguring the post-modernists' attempt to abolish the spare glass high-rise, Wright declared that he had 'broken the box' of Victorian domestic architecture and went on to explore organic forms, finding further inspiration in Mayan and Asian design.

Wright started out as an admirer of the Arts and Crafts tradition but he neverthe- less celebrated machine technology. The show illustrates his experimentation with new construction techniques, including the use of prefabricated concrete blocks arrayed with geometric ornamentation.

Like most architectural exhibitions, Frank Lloyd Wright: Architect, lacks a direct spatial experience of the fully realised work. Wright's intricate leaded glass windows and plaster friezes appear out of context here and can only hint at their intended glory as part of his overall vision with its stress on a building's rela- tionship to nature and its site.

But this vast exhibition will send visitors out marvelling anew at Wright's built work. Happily they can find one of his greatest creations near at hand by going up Fifth Avenue to the recently refurbished Guggenheim Museum.

Previous page

Previous page